Tax Policy – Proposal to Increase New York Beer Tax

Commercial brewing of beer has been part of New York state since 1632, when Dutch settlers opened the first brewery in Manhattan. The brewing tradition continued through the centuries, peaking in 1876 with 393 breweries, before the Volstead Act prohibited production and sale of alcohol in 1920. Taxation of beer in New York can be traced back to those same settlers as a vital source of revenue in New Amsterdam.

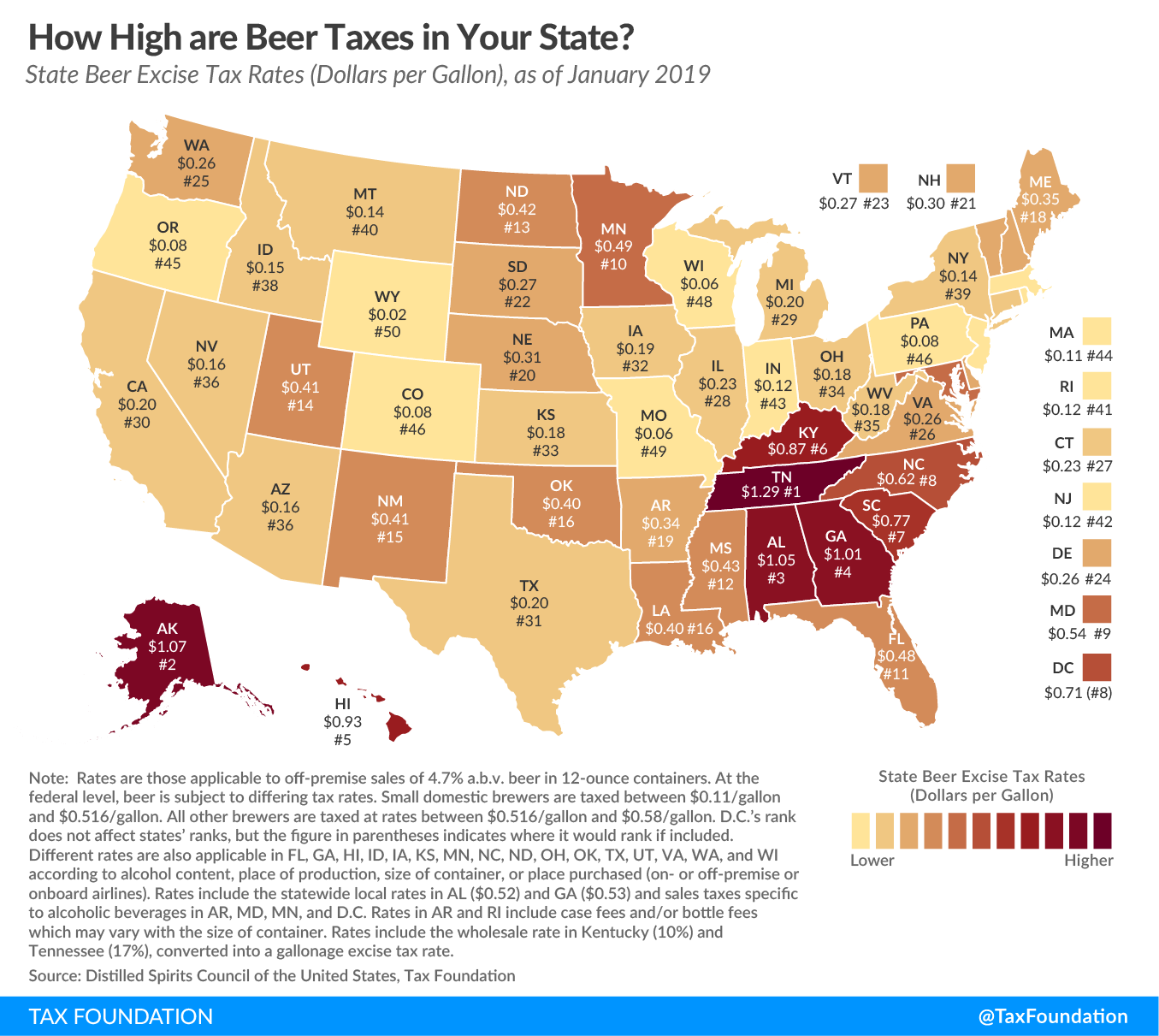

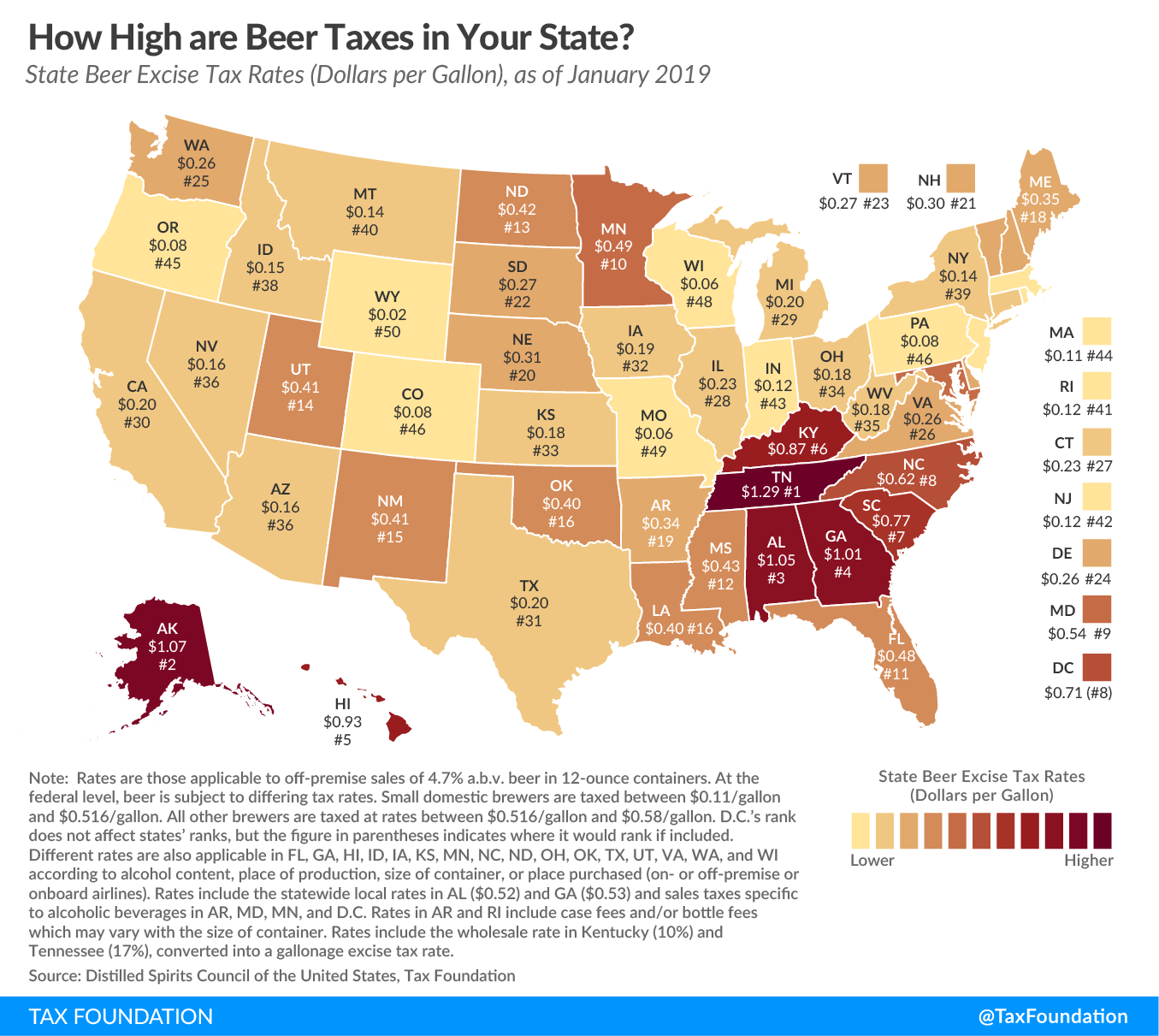

Though much has changed in New York over the last 400 years, lawmakers still look to beer taxes when seeking new revenue. In late December, New York Assemblyman Harvey Epstein (D) proposed to increase the state excise tax on beer to $0.30 per gallon—more than double the current rate of $0.14. If enacted, the additional revenue (the bill estimates $51 million) would be split among two state universities in New York.

Lawmakers apply excise taxes on beer for several reasons. They can be used when seeking to change behaviors by increasing the cost of beer and thus reducing the amount consumed. They can also be imposed to pay for a state’s health care expenses related to alcohol abuse, thus internalizing some of the societal cost of alcohol consumption. Further, they are sometimes used as a more general revenue source.

The rationale for Assemblyman Epstein’s proposal is to raise revenue for educational programs, but this excise tax is an inappropriate and non-neutral revenue source for this objective.

Excise taxes certainly have their place, especially when they are imposed as a user-fee. The gas tax is the typical example, where the amount of fuel purchased acts as a rough proxy for a driver’s contribution to road wear-and-tear as well as traffic congestion. The funds collected from the tax can then be used to fund the roads that drivers use. This design follows the benefit principle, that taxes paid are connected to the public benefits one receives.

However, unlike the gas tax, the bill in question neither abides by the benefit principle nor seeks to internalize a societal cost of alcohol use. While there might be significant correlation, there is surely no causal relationship between drinking beer and attending public college. In effect, the proposal is simply a non-neutral measure imposed on a single industry to raise general fund revenue. General fund revenue should instead be raised through broad general taxes.

In his bill, Assemblyman Epstein refers to the Tax Foundation’s analysis of state beer taxes (see map below) and concludes that the tax in New York is among the lowest in the country. While that is true, it is not a good reason to increase taxes, especially in a state that broadly has a high tax burden. On the contrary, there are good reasons for keeping state taxes competitive. In fact, keeping the rates competitive is aligned with New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s (D) action of lowering license and compliance costs in order to foster growth of the craft brewery industry. Today, New York is home to 400 breweries, surpassing the old record from 1876.

Further, excise taxes on beer are already a large expense for breweries. The Beer Institute, an industry trade group, argues that “taxes are the single most expensive ingredient in beer, costing more than labor and raw materials combined,” citing an analysis that finds that the sum of taxes levied on the production, distribution, and retailing of beer exceeds 40 percent of the retail price. In addition, there are other factors that can drive the price of beer up or down in a state. According to one analysis, which looked at average prices for two of the most popular brands, retail prices in New York are not among the lowest in the nation: New York’s average price for a 24-pack case is above higher-taxed Virginia, Connecticut, and New Hampshire.

Source: Tax Policy – Proposal to Increase New York Beer Tax