Tax Policy – Taxing Nicotine Products: A Primer

Key Findings:

- The American nicotine market is developing faster than ever due to introduction of non-combustible recreational nicotine products. These new products, along with a greater consciousness about the dangers of smoking, have prompted millions to give up smoking. This contributed to federal and state excise tax collections on tobacco products declining since 2010.

- Excise taxes are commonly employed to discourage certain behaviors. They do this by decreasing both supply and demand for a product via price increases. They are also imposed to price in externalities associated with consumption of specific goods.

- Current federal tax proposals seek to tax electronic nicotine delivery systems (vapor products) at the same rate as traditional cigarettes. H.R. 4742 was approved by the House Ways and Means Committee in October 2019 and suggests taxing based on nicotine content.

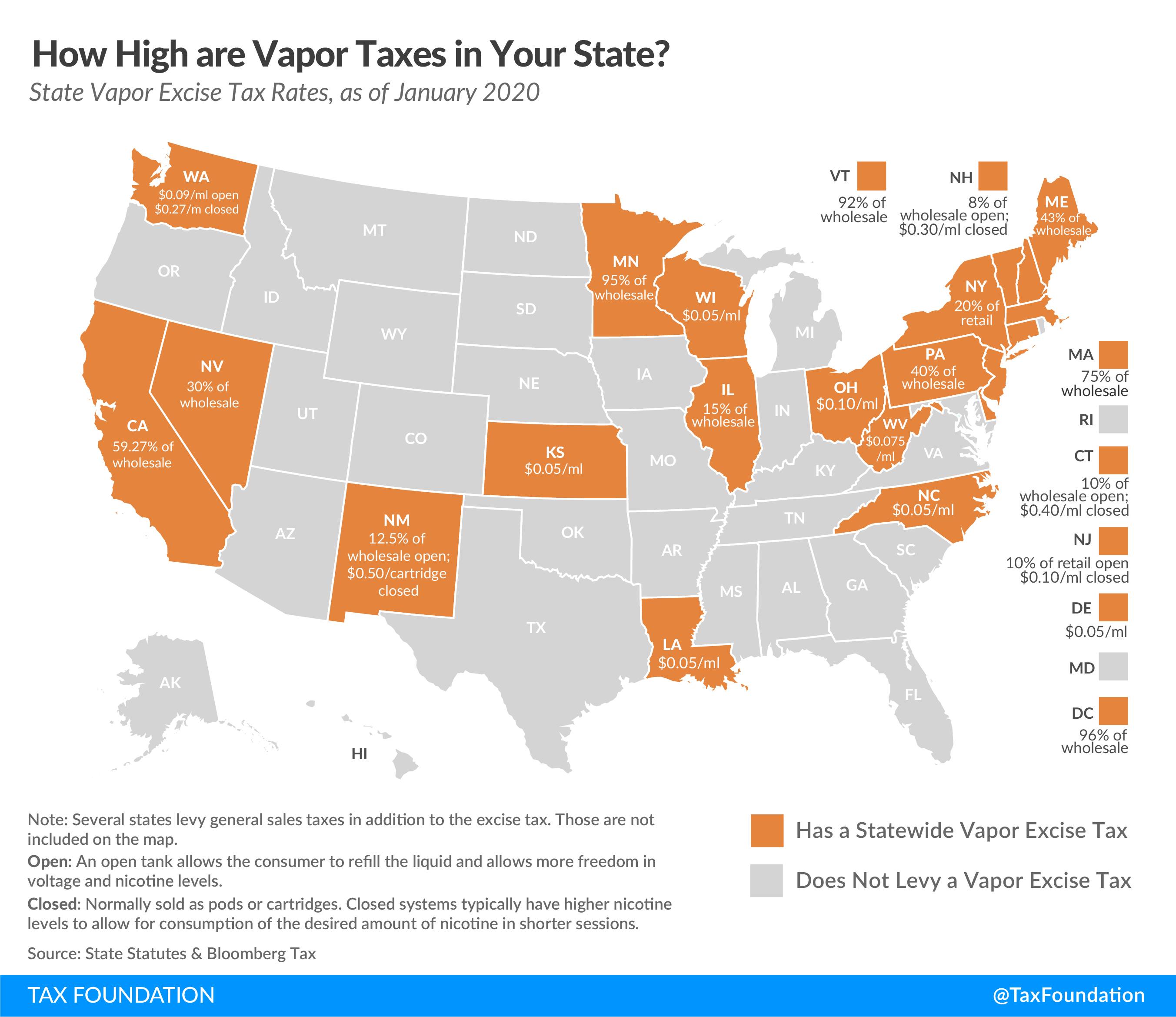

- Twenty-one states currently tax nicotine products, but they do so in different ways. States tax based either purely on price (ad valorem), purely on volume (specific), or with a bifurcated design at different rates for open and closed tank systems. More states are expected to introduce taxes on vapor products in 2020.

- From a pure public health standpoint, the justification for taxing recreational nicotine products can seem weak. Vapor products, heated tobacco, snus, and nicotine pouches are all thought to be considerably less harmful than cigarettes, which means substitution from cigarettes to any of these products should be encouraged. While youth uptake is a very real concern, tax policy is not the appropriate way to address it.

- An excise tax on vapor products should be specifically based on volume as this design is the simplest way to tax a good. Specific taxation does not require valuation and as such does not require expensive tax administration, as is the case for ad valorem where vertically integrated companies must compute a value to determine tax liability. Taxing the value of a good also hurts consumer choice and product quality. Taxing the strength by nicotine content uses the wrong proxy for the harm associated with vaping. In effect, this tax practice encourages higher consumption quantities of lower nicotine-containing liquids.

- An excise tax on snus should be based on weight to simplify taxation of both pouches and loose tobacco-snus products. Presumably any externalities associated with consuming snus are related to the amount of tobacco consumed by the user, and a weight-based tax would capture this best.

- Non-tobacco nicotine pouches (alternative nicotine products) should also be taxed based on weight at a rate relative to their low harm profile. The product can be consumed in different forms but using weight ensures a simple tax design with low compliance costs.

- Taxation of heated tobacco products could be designed like cigarette taxes, a specific amount per stick, as the product most often is sold in sticks or small pods. This structure captures the harmful behavior and remains neutral. The level of tax should be carefully considered by lawmakers and be relative to the harm.

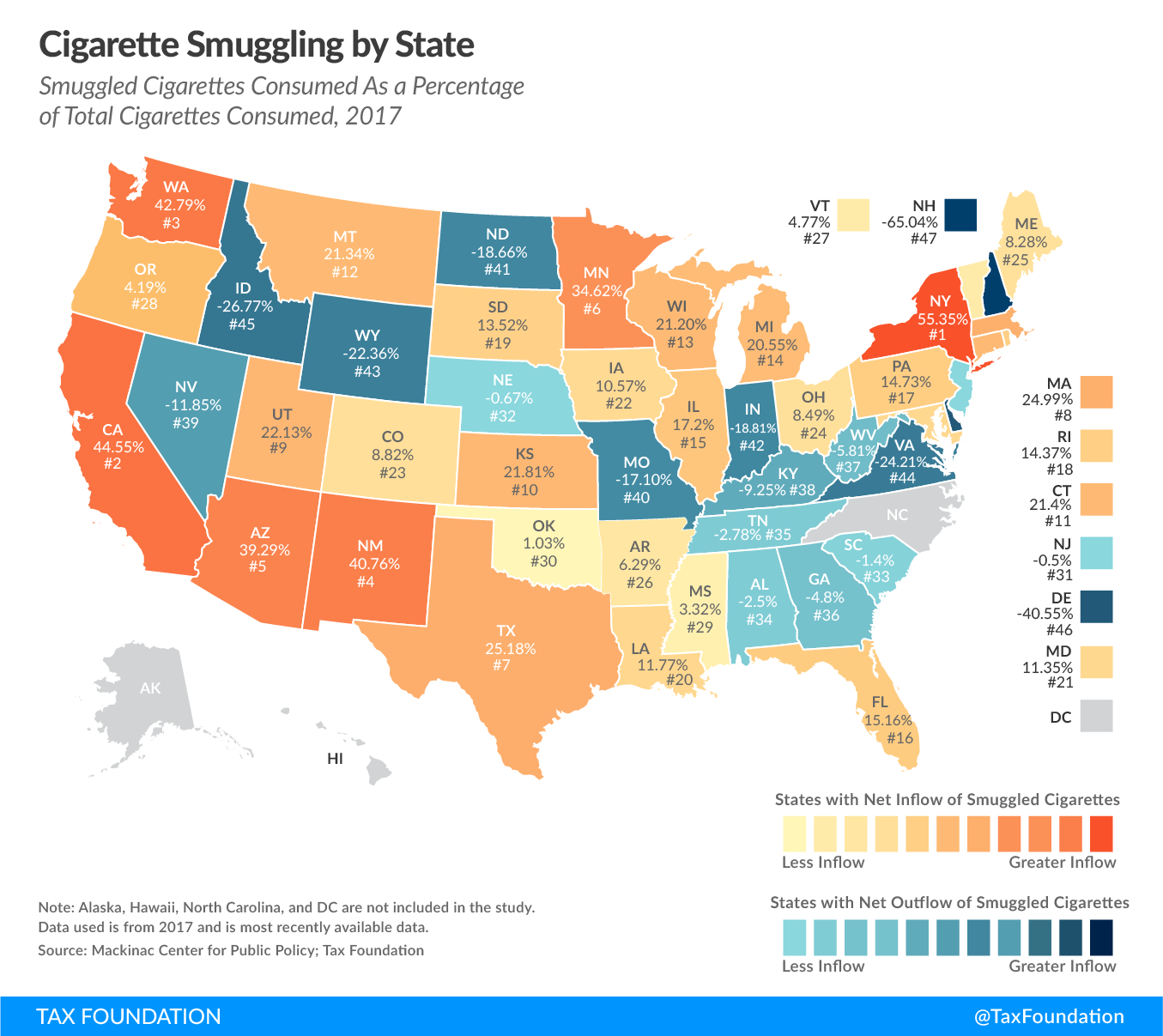

- The large black market for cigarettes should serve as a cautionary tale for lawmakers when designing nicotine products taxation. Inefficient taxation of nicotine products could lead to increases in illegal trade. This inefficiency increases when regional as well as global differences in tax levels get bigger.

- Multiple levels of government are considering banning flavored products in all tobacco categories. Bans can be observed as infinite taxes and share high taxes’ unfortunate effects on adult smokers’ ability to switch from cigarettes to a less harmful product.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Why Levy Excise Taxes?

- Federal Legislative Proposals and Strategies

- State Legislative Proposals and Strategies

- Harm Reduction and Modified Risk

- Design Considerations

- Economic Efficiency

- Equity

- Transparency

- Collectability

- Revenue Production

- Black Market Risks

- Bans

- State-by-State

- Conclusion

Introduction

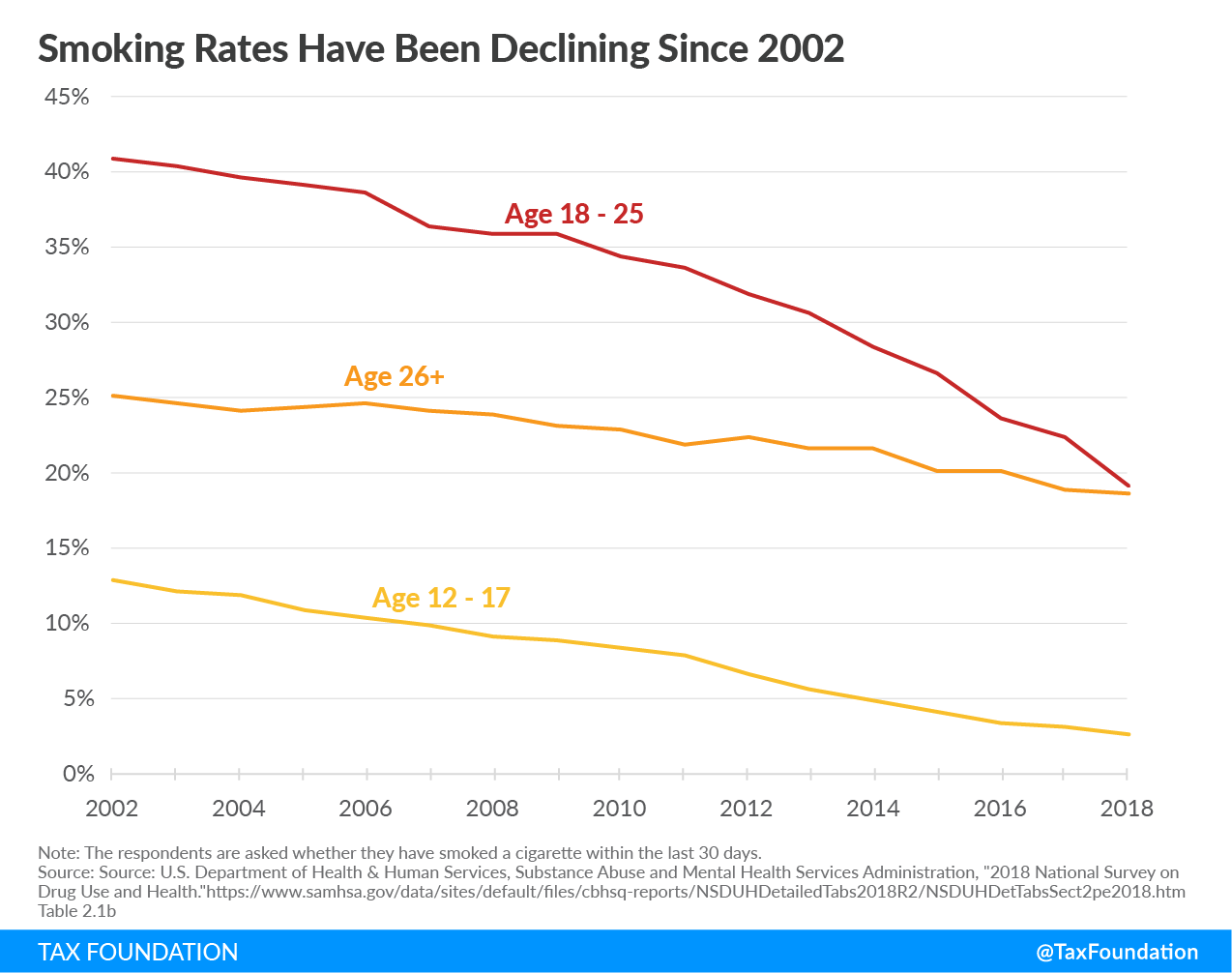

The nicotine market in America has changed dramatically over the last decade. The introduction of electronic nicotine delivery systems (also called vapes or e-cigarettes) is probably the largest disruption to the nicotine market since cigarettes were made popular (and, more importantly, cheap) ahead of the two world wars. By the end of World War II, over 40 percent of Americans smoked cigarettes, but today, millions of people are giving up cigarettes and only 13.7 percent of the population smokes regularly.[1] Some former smokers have substituted cigarettes with electronic cigarettes, oral smokeless tobacco, or other tobacco-free nicotine products. This trend can be observed in the sales figures: according to Wells Fargo, combustible cigarette volumes have been declining at historically high rates.[2] Not only are cigarette volumes declining, but between the start of 2015 and the close of 2018, cigarette sales have dropped from 87.7 percent to 82.5 percent of the total tobacco market.

Vapor products entered the U.S. market in 2007. While purchases started out in the relative obscurity of shopping mall kiosks and through online sales, vapor products are now a common sight at gas stations, convenience stores, and dedicated brick and mortar vapor stores. Wells Fargo estimates that vapor products now make up close to 5 percent of the total tobacco market. The growth trend is expected to continue as a result of vapor products’ volume growth of up to 15-20 percent through 2023.[3] Smokeless tobacco makes up 8.4 percent and cigars 4.5 percent.[4]

Roughly 9 percent of adult Americans said they vaped regularly or occasionally in 2018. Among 18-29-year-old Americans, 20 percent said they vaped.[5] However, vapor products are not the only harm-reducing nicotine product widely available on the American nicotine market. Snus products are the only tobacco product to be granted a modified risk order by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.[6] Snus is not a new product like vapor products; it has a rather long history in Scandinavia, where it is more widely consumed than cigarettes. In America, 3.4 percent of adults reported using smokeless tobacco in 2016. While men are generally more likely to consume tobacco of all kinds, the difference is very significant in relation to smokeless tobacco, where 6.6 percent of men reported use. Only 0.5 percent of women reported use in 2016.[7]

The newest widely available product is tobacco-free nicotine pouches.[8] It is a product like chewing tobacco or snus, but entirely without tobacco leaves. Instead, the product is a chewing gum-based pouch with nicotine derived from tobacco. Finally, heated tobacco products are also entering the U.S. market. These products heat the tobacco rather than burn and as such do not create any smoke.

As the popularity of nicotine products grows, so does the debate over their public health implications. Some reports have stressed the risk of vaping causing severe damage to consumers’ health. Lawmakers and health professionals have also voiced concerns that vapor products could serve as a gateway to traditional tobacco use, particularly among minors.

However, others view nicotine products as a viable smoking cessation method, a net benefit for public health. Several studies suggest that nicotine products can play a significant role in harm reduction by reducing consumption of traditional cigarettes.[9]

Nicotine products are manufactured differently than traditional combustible cigarettes, and there is some consensus that they have significantly lower health risks than cigarettes; this has important implications for taxation. On one hand, a declining number of smokers is a positive development for public health, but on the other, cigarette tax has been a major revenue tool for many states. One of the main challenges for policymakers is determining how these emerging products should be treated with respect to tax policy. Should non-tobacco be subject to an excise tax at all and if so, at what level? If taxed, should they be included in the tobacco category or have a standalone tax category?

This paper will discuss whether there is a rationale for taxing nicotine products (beyond any inclusion in the general sales tax) and will examine how the excise taxes of these products could be designed in a more principled manner. The first section of the paper presents a short introduction to excise taxes. Next, the paper walks through key federal proposals for taxation of nicotine and discusses different states’ strategies for taxation. The third section is a discussion of design and different risks associated with not designing principled taxes. The final part of the paper outlines the current state of taxation of vapor products and snus.

Definitions for a few terms used throughout this paper follow.

- Electric Nicotine Delivery System, E-cigarette, or Vapor product: Products consisting of a battery, atomizer, and nicotine cartridge. Products generally come in two varieties: open systems and closed systems.

- Open tank: A vapor product that allows the consumer to manually refill the liquid and allows consumers more freedom in voltage and nicotine levels.

- Closed tank: These systems are normally sold as pods or cartridges. The best-known product within the category is JUUL. Closed tank systems normally have higher nicotine levels per milliliter to allow for consuming the desired amount of nicotine in shorter sessions.

- Heated tobacco product: Creates a vapor rather than smoke as the tobacco is not combusted but only heated.

- Snus (moist snuff): A pasteurized moist powder tobacco originating from Sweden. The products are used like American dipping tobacco but do not require spitting.

- Nicotine pouches or alternative nicotine product: A gum base with nicotine added.

Why Levy Excise Taxes?

Excise taxes are indirect taxes generally levied on specific products or activities instead of a general tax base, like income or sales. They are sometimes employed as Pigouvian taxes, or sin taxes, to price in externalities. An externality, in economics terms, is the side effect or consequence of an activity that is not reflected in the cost of said activity. For instance, some of the health-care costs of smoking are covered by government; another is secondhand smoke affects nonsmokers. Levying an excise tax on these products can serve to recoup some of the cost of these externalities. Sin taxes are also used to discourage consumption of a product that imposes costs on others.[10] Thus, excise taxes are widely levied on “sinful” products such as gambling, alcohol, and tobacco.

Excise taxes can also be employed as user fees. The role of excise taxes as a user fee is best understood with the example of the gas tax. The more you drive, the more you use government-funded roads. The gas tax is an estimate of the costs relative to how much a person uses the roads—at least in theory.

These two examples of how to think about excise taxes illustrate the fundamental policy trade-off related to the tax. States cannot simultaneously maximize for revenue or behavioral adjustment as the two are in tension with each other. It is obvious that there would be no revenue if lawmakers successfully design an excise tax eliminating smoking. This is illustrated by presidential candidate and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s assertion that “[i]f it were totally up to me, I would raise the cigarette tax so high the revenues from it would go to zero.”[11]

It would be difficult to tax nicotine use into nonexistence, but there is no doubt that taxes influence behavior. The laws of supply and demand dictate that as prices go up consumption goes down, although this is a simplification. The deterrent effect of excise taxes is greatest on the occasional user, as heavy consumers tend to have relatively inelastic demand. That means their behavior does not change as much because of price changes. When you add the addictive qualities of nicotine to the equation, heavy users might seek to satisfy their addiction with alternatives—legal and illegal—rather than quitting.

Governments rely on excise taxes. In 2018, excise taxes made up 2.9 percent of the federal revenue,[12] and tobacco taxes comprised an average of close to 2 percent of state tax collections.[13] That year, the federal government collected $11.5 billion in taxes on cigarettes, but this is down 22 percent in nominal terms since 2010. Similar declines are happening in state collections. Collections on other tobacco products are also in decline.[14] These developments have prompted lawmakers to look at alternative revenue sources such as taxes on nicotine products.

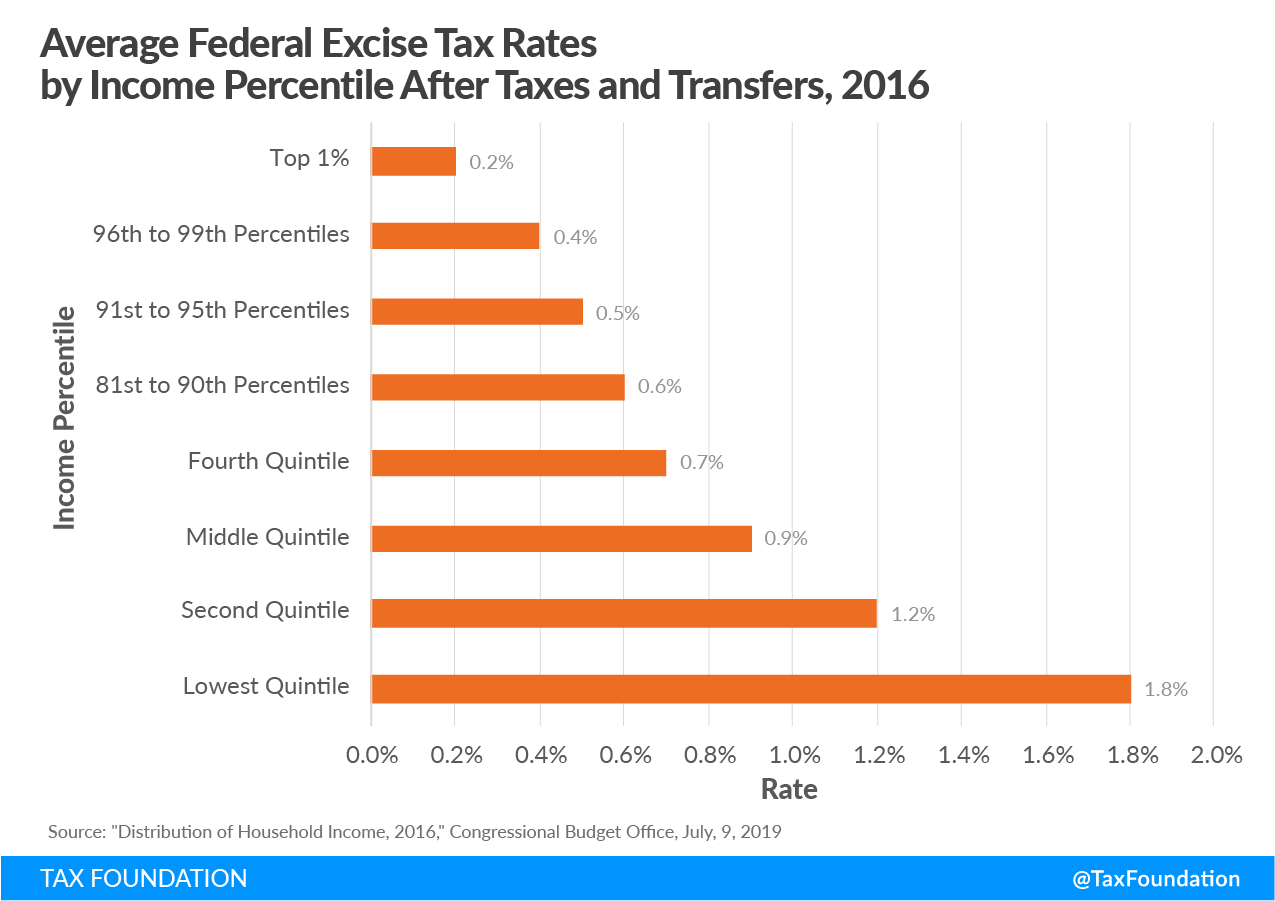

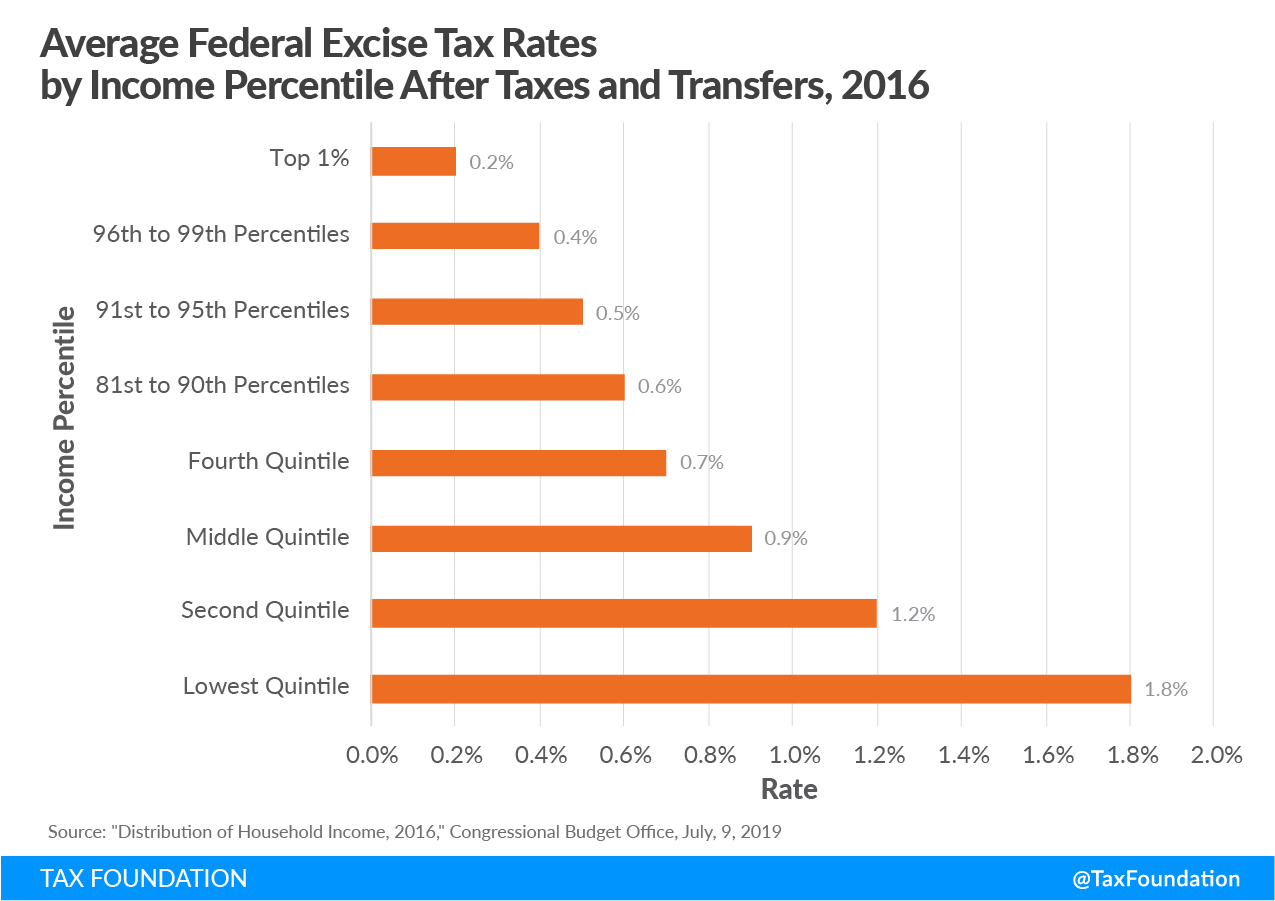

Lawmakers imposing excise taxes should keep in mind that they affect people differently according to their income. In 2016, the top 1 percent on average paid an effective rate of 0.2 percent in federal excise taxes. The lowest quintile faced an average effective rate of 1.8 percent in federal excise taxes. While higher earners spend more and as a result also pay more in excise taxes in real terms, excise taxes as a percentage of their spending is significantly lower compared to low-income Americans.

The above is true for excise taxes in general, but taxes on tobacco are even more regressive. Americans at or below the poverty line are more likely to use nicotine, which contributes to the regressivity of these taxes.[15]

Legislative Proposals and Strategies

Federal Taxation

As of January 2020, no federal excise tax is levied on vapor products or nicotine pouches,[16] but in 2019 several lawmakers called for a federal tax on vapor products. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) introduced legislation to enact a vapor products excise tax at the level applied to cigarettes, which is currently $1.01 per pack.[17] A second Senate bill, sponsored by Sen. Mitt Romney (R-UT) and Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-OR), would ban most currently available vapor products and implements an excise of $1.01 per device and a similar tax on liquid containing less than 5 percent nicotine by volume.[18]

There is also a bill in the House of Representatives, sponsored by Rep. Tom Suozzi (D-NY) and Rep. Peter King (R-NY), which, if enacted, would impose an excise tax on vaping of $50.33 per 1,810 milligrams of nicotine,[19] equivalent to the current tax on 1,000 cigarettes. This bill has advanced the furthest and is the most detailed, and thus will be the focus of the subsequent section.

While the focus of the bill is vapor products, the bill’s definition of taxable nicotine is very broad and captures all non-tobacco nicotine products. That means tobacco-derived nicotine pouches for oral consumption would be subject to the tax as well. The following table includes calculations of the bill’s effective rates on several popular nicotine products.

|

Source: Tax Foundation calculations. |

|||||

| Product Type | Brand | Volume | Nicotine content | Nicotine content (mg) | Excise tax level ($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vapor (closed system) | JUUL 4-pack | 2.8 ml | 59 mg/ml | 165 | $4.59 |

| Vapor (open system) | Bottle 30 ml | 30 ml | 10 mg/ml | 300 | $8.34 |

| Vapor (open system) | Bottle 10 ml | 10 ml | 5 mg/ml | 50 | $1.39 |

| Vapor (closed system) | MyBlu 2-pack | 3 ml | 40 mg/ml | 120 | $3.34 |

| Nicotine pouch | ZYN | 15 pouches | 6 mg per pouch | 90 | $2.50 |

As shown in the table, the tax would be high across all types of products, with the bigger tax on high-nicotine liquids. In fact, the tax is significantly higher on these products than on a pack of traditional cigarettes, which is taxed at $1.01 at the federal level. While this may be the goal of the bill, the problem is that nicotine content alone does not determine nicotine absorption, even assuming that nicotine is the appropriate target of the tax. Differences in vapor device design, nicotine product design, and consumption patterns[20] have major implications for how much nicotine is absorbed by the consumer. The high level of taxation also hurts smokers’ ability to switch from cigarettes to harm-reducing products as they would be more expensive at retail.

The tax does not target the behavior it seeks to discourage, nor does it capture the externality—in this case, the health risks connected to the frequent use behavior. Instead it targets nicotine, which is the addictive substance in the products, but not the main harmful ingredient. Taxing based on nicotine content would favor low-nicotine liquids and could encourage increased consumption in the quantity of liquid. The proposal also gives a competitive advantage to open systems as open systems allow the user to customize the device. Increasing the voltage in these systems can deliver higher nicotine yields and imitate the nicotine delivery of traditional cigarettes, even when using low-nicotine liquids.

State Taxation

All states tax tobacco products, but only 21 states and the District of Columbia tax vapor products.[21] Eleven of these states introduced their tax in 2019 and more states will likely pass tax bills on vapor products in 2020. Currently, three designs are utilized at the state level: pure ad valorem, pure specific, or a bifurcated system for open and closed tanks. There are also different rationales for levying excise taxes on vapor products, with some states prioritizing capturing revenue and others focused on deterring use.

States like Minnesota and California have included vapor products in their “other tobacco products” category, whereas other states have enacted a special excise tax for the product. Most states with a high ad valorem tax on vapor products have broadened existing tobacco tax categories to include vapor products, while states with specific vapor excise taxes typically have lower rates. The last section of this paper outlines the approaches of the 21 states that currently tax both vapor products and snus products.

Nicotine pouches are taxed in a few states by including them in their definition of “tobacco products,” but generally without taking legislative action. This can lead to confusion for businesses and consumers, who might be unaware whether the product is taxed.

There are several issues with the way states tax the products today. First, only very few states have modernized their definitions of tobacco and nicotine products to encompass the variety of novel products available to consumers. Virginia is one of the states that has done so. Their tax code now includes definitions of the following products:

“Alternative nicotine product” means any noncombustible product containing nicotine that is not made of tobacco and is intended for human consumption, whether chewed, absorbed, dissolved, or ingested by any other means. “Alternative nicotine product” does not include any nicotine vapor product or any product regulated as a drug or device by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under Chapter V (21 U.S.C. § 351 et seq.) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

“Heated tobacco product” means a product containing tobacco that produces an inhalable aerosol (i) by heating the tobacco by means of an electronic device without combustion of the tobacco or (ii) by heat generated from a combustion source that only or primarily heats rather than burns the tobacco.

“Liquid nicotine” means a liquid or other substance containing nicotine in any concentration that is sold, marketed, or intended for use in a nicotine vapor product.

“Nicotine vapor product” means any noncombustible product containing nicotine that employs a heating element, power source, electronic circuit, or other electronic, chemical, or mechanical means, regardless of shape or size, that can be used to produce vapor from nicotine in a solution or other form. “Nicotine vapor product” includes any electronic cigarette, electronic cigar, electronic cigarillo, electronic pipe, or similar product or device and any cartridge or other container of nicotine in a solution or other form that is intended to be used with or in an electronic cigarette, electronic cigar, electronic cigarillo, electronic pipe, or similar product or device. “Nicotine vapor product” does not include any product regulated by the FDA under Chapter V (21 U.S.C. § 351 et seq.) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.[22]

Poor definitions lead to disproportionate treatment of similar products. In Minnesota, for instance, the tax is levied differently when the nicotine solution is mixed in-state versus products imported in their final consumable form.[23]

A second issue, which has surfaced in the states with vapor taxes, is tax avoidance. In Pennsylvania, authorities reported that due to no enforcement, out-of-state companies would not report or pay taxes, even though they are required to do so.[24] The high Pennsylvania tax (40 percent of wholesale value) had a considerable impact on the market, and roughly 100 vapor stores had closed within one year of the application of the tax.[25]

Harm Reduction and Modified Risk

Before discussing the trade-offs in nicotine tax policy design, it is important to introduce the concept of harm reduction, which is the approach that it is more practical to reduce harm associated with use of certain goods rather than avoiding it completely through bans or punitive level taxation. It is a shift from a way of thinking that has previously dominated public health cessation efforts. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) acknowledges harm reduction through its Premarket Tobacco Product Application (PMTA) and Modified Risk Tobacco Products (MRTP) classifications, where certain tobacco and nicotine products can be classified as less harmful than others. The first ever MRTP order was granted to Swedish-style snus products, allowing the manufacturer to claim that use of these MRTP products lowers consumers’ risks compared to the use of cigarettes.[26]

This strategy is relevant for a couple of reasons. According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), 34.3 million Americans smoke.[27] Out of those, about 70 percent are interested in quitting,[28] but the current success rate is only about 7 percent. Among younger smokers it is slightly higher, about 10 percent.[29] The main reason for the low success rate is the addictive nature of nicotine. To put it simply: it is very difficult to quit.

One way of getting the 24 million Americans who want to quit away from cigarettes is to offer less harmful nicotine alternatives as cessation tools.

The numbers of smokers interested in quitting also tell us that 10 million Americans are not interested in giving up their nicotine habit. States should be looking to offer these Americans options for nicotine consumption that are less harmful than cigarettes. The nicotine products discussed in this paper can play an important role in this.

Protecting access to harm-reducing products is connected to excise tax design as these products are substitutes. Taxing them relative to their harm is an obvious strategy. That strategy is utilized in a couple of states, which have introduced provisions in their tax code cutting taxes in half if the FDA classifies a product with a MRTP order. These provisions should be encouraged as they respect the policy spillover effect. The term “policy spillover” means that policies interact with each other. In excise tax policy, increases or decreases in tax levels of certain goods can affect other consumption of other goods that might be substitutes. The effectiveness of cigarette excise taxes goes up when cheaper substitutes are widely accessible. The concept is discussed in more detail below.

Design Considerations

From a pure public health standpoint, the rationale for taxing nicotine products can seem weak. For instance, it is generally believed beneficial for society every time a smoker becomes a vaper. More research relating to the potential harm-reduction qualities of vapor products is needed, but for now the consensus is that vapor products are less harmful than traditional combustible tobacco products. Public Health England, an agency of the English Ministry for Health, concludes that vapor products are 95 percent less harmful than cigarettes. [30] In other words, vapor products could be a key tool in the fight against tobacco-related morbidity and mortality.

In relation to taxation of vapor products, that is a key factor when considering the interaction between vapor taxes and cigarette taxes. Vapor products and cigarettes can be economic substitutes.[31] That means excise taxes on harm-reducing vapor products at high rates risk harming public health by pushing vapers back to smoking. By looking at cessation behaviors in lieu of a tax increase on vapor products, a recent publication found that 32,400 smokers in Minnesota were deterred from quitting cigarettes after the state implemented a 95 percent excise tax on vapor products.[32]

The substitutive effect is evident looking at the smoking rates in the U.S. There is some correlation, and perhaps causality, between recent growth in the vapor market and a declining cigarette market. While vaping has been growing in many states, the decline in smoking has accelerated—especially among teens and young adults.

As a revenue tool rather than a public health tool, a tax might make more sense. Some of the decline in revenue from traditional tobacco can be made up by taxing nicotine consumers more. However, assuming the rationale for taxing tobacco involved considerations beyond mere revenue, the harm-reduction potential of vapor products may advise against this, and this rationale still leaves questions around the justification for targeting a single product and group of consumers for revenue. Revenue-raising measures should be broad-based with low rates.

To the extent that legislators do choose to tax nicotine products, they should design a principled excise regime. Legislators should focus on raising revenue in a simple, neutral, transparent, and stable manner. Levying taxes based on these principles limits the adverse effects on the economy and individual consumers.

The first step when designing a principled tax is defining the taxable good. Currently the states define vapor products, snus, heated tobacco, and nicotine pouches in different ways, which affects how the tax is imposed. For vaping, it might be advisable to use the FDA’s definition of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems, which regards it as an umbrella term for “noncombustible tobacco products containing an e-liquid that, when heated, creates aerosol that a user inhales.”[33] This would ensure that state taxes and potential federal taxes treat the products similarly.

Definitions are equally important for other novel nicotine and non-combustible products. As outlined above, Virginia has updated its tax code to more accurately reflect the market for nicotine products. This practice is advisable as it allows excise taxes to better capture the targeted activity and treat different products differently when appropriate. Modernized categories and tax levels also allow consumers to use price as a proxy for harm and supports harm-reducing behavior. This practice is important at both the state and federal level. Currently, heated tobacco sticks could be categorized as cigarettes under federal tax code 26 U.S.C. § 5702(b) even though the product produces no smoke. This categorization takes away the financial incentive for smokers to switch to less harmful products.

In the following section, the paper reviews some of the trade-offs and criteria for developing principled taxes on nicotine products.

Economic Efficiency

It is economically inefficient when consumers and companies make decisions based on tax avoidance.[34] Efficient revenue-focused taxes should be designed to be neutral and have the least effect on decision-making. Legislators should pass regulations and enforce them rather than adopt taxes to achieve regulatory goals.

While the principle of a neutral and efficient tax can stand in obvious opposition to taxing nicotine products in order to deter use, it should still be respected in relation to taxation of different categories. For instance, the tax should not favor open tanks versus closed tanks or bundled versus unbundled products.

To this end, the tax should be specific, based on quantity. In terms of vapor products, the obvious choice is to tax the liquid based on volume (e.g., a certain amount per ml).[35] Applying similar levels of tax to nicotine products with similar qualities respects the principle of a neutral tax by not encouraging certain products over others. Conversely, taxing the value of a good (ad valorem) hurts consumer choice and product quality as it incentivizes manufacturers and retailers to reduce prices to limit tax liability. It also incentivizes downtrading, which is when consumers move from premium products to cheaper alternatives. Downtrading effects do not reduce harm and have no relation to any externality the tax is seeking to capture.

The level (dollar amount) of the excise tax should reflect the harm of nicotine products relative to traditional tobacco products.

Taxing based on strength or nicotine content, as proposed on a federal level, has a significant flaw. A strength-based excise system for vapor products results in high nicotine-liquids becoming relatively more expensive compared to low nicotine-liquids. The logical outcome would be that consumers switch to low-nicotine liquid and customizable devices. Recent research has shown that the use of low-nicotine liquids may be associated with “compensatory behavior” as users’ drags change to be deeper, more frequent, and longer to achieve the nicotine level that reduces their desire to smoke. This contrasts with a policy goal of limiting users’ exposure to vapor by encouraging behavior opposite of the desired goal.[36]

Policymakers seeking to use excise taxes to nudge behavior should also keep in mind that taxing does not happen in a vacuum. Given the substitutive effect between vapor products and traditional cigarettes, policymakers must consider how taxes independently levied on tobacco and nicotine products interact. Increasing taxes on vapor products reduces their appeal and market share, effectively making it more difficult for adult smokers to switch. That means excise taxes on cigarettes are less effective in discouraging smoking when vapor products are also taxed.[37] This effect is a so-called policy spillover. If the policy goal of taxing cigarettes is to encourage cessation, vapor taxation must be considered a part of that policy design.

An excise tax on snus should be weight-based to simplify taxation of both pouch and loose snus products. Presumably any externalities associated with consuming snus are related to the amount of tobacco consumed by the user, and a weight-based tax would capture this best. If a given product is granted a modified risk order by the FDA, policymakers should consider lowering the tax rate on that product, as it allows consumers to use price as a proxy for harm.

The key to taxing nicotine pouches is getting the definitions right. These products are still relatively new and should not be lumped in with existing tobacco products as they do not contain tobacco. To properly tax these products relative to their harm, both federal and state lawmakers need to develop independent definitions to make sure the target of a tax is also what is taxed. Taxing based on weight is the simplest design. The product is used like snus and the same arguments apply. An argument could potentially be made to tax based on strength if nicotine addiction is the target of the tax. However, this would make collections more technical, require expensive enforcement, and would not respect the relative harm compared to traditional tobacco products.

Finally, taxation of heated tobacco should be designed like cigarette taxes as the product is most often sold in sticks or as small pods. This structure captures the harmful behavior best and remains product-neutral. The level of tax should be carefully considered by lawmakers because as long as the product is less harmful than cigarettes, the level of taxation should reflect this. Taxation of heated tobacco requires careful consideration when defining heated tobacco products as the product should not be included in the cigarette definition.

Equity

The equity of tax policy can be observed in two dimensions: horizontal and vertical. The horizontal equity analysis focuses on whether two similar purchases are taxed in the same way and at the same rate. In this regard specific taxation is preferable as it avoids discriminating between product design while capturing the targeted behavior. A nicotine product with similar qualities and in similar quantities should have equal tax liability regardless of design or price, a principle ad valorem taxes ignore. Minnesota’s tax code is particularly flawed in this regard because the tax is levied differently when the nicotine solution is mixed in-state versus products imported in their final consumable form.

Designing a tax for vapor is challenging because, unlike cigarettes, vapor products are not all similar. Closed systems typically have higher nicotine content than open systems. However, legislators could consider establishing a tiered system, where open systems are taxed at a lower rate than closed systems, with different rates designed to equalize taxation and keep it neutral, not introduce unnecessary disparities.

Weight and quantity-based taxation of snus, heated tobacco, and nicotine pouches guarantees horizontal equity as the products can be consumed in different shapes and sizes. Weight is the most appropriate proxy for determining tax liability as it reflects the amount of good purchased regardless of final consumable shape.

The other dimension is vertical equity, which describes the tax burden in relation to income. As already discussed, excise taxes on tobacco and nicotine are regressive in nature due to the above-average consumption of lower income groups. That means lower-income Americans, relative to higher earners, are paying a higher percentage of their disposable income in excise taxes. But aside from that, excise taxes on nicotine products are inherently unstable and nonneutral, and policymakers are well-advised to avoid relying on this revenue to fund broad-based government programs. The revenue should instead be used to cover the externalities associated with the excised good.

Transparency

Taxes should be easy to calculate and understand for consumers and businesses. A specific tax is easier to calculate and understand for both consumers and businesses as it is based on quantity, volume, or weight. Simple taxes lower compliance costs and make it easier for tax authorities to enforce the tax.[38]

In a situation where a state levies an ad valorem excise tax on the wholesale price of a good on which a federal excise tax is levied, the state would be taxing a tax. This happens because when the product reaches the state wholesaler, the federal excise tax is already built into the price, resulting in a tax on a tax. This effect limits the transparency for the consumer but can be avoided by levying the tax on manufacturer price or better yet by taxing based on quantity. This issue is not unique to nicotine taxation, but is an important consideration considering the multiplier effect in states that already have high ad valorem taxes.

Collectability

It can be expensive to collect taxes both for businesses and governments. A specific tax design is the administratively simplest and most straightforward way for governments to tax a good as it does not require valuation and as such does not require expensive tax administration. For instance, in vertically integrated companies (some vape shops both manufacture and retail vapor liquid), taxable value must be computed to estimate tax liability. Taxing based on quantity rather than value makes it easier for governments to forecast revenue as it is not affected by changes in consumer brand preference or retail prices.

Revenue Production

Collections on the excise tax should be worthwhile relative to the burden placed on business and governments. The available data on revenue collections from vapor taxes across the states is limited, but where available they show limited revenues regardless of design. Problems with tax definitions and trade compliance are likely the main reasons for this. The taxes do not capture the full market, so it is key that lawmakers develop a regulatory framework to establish some control with the market.[39]

Revenue collected through excise taxes on nicotine products should not be considered stable—excise revenues seldomly are—and the market is both young and volatile. Keep in mind that cigarette tax revenue is notoriously difficult to predict, and the cigarette market is, contrary to the vaping market, a mature market. Legislators and state revenue forecasters should be aware of this when calculating the revenue expectations and appropriating funds. Specific taxes could also be more stable, if they are adjusted for inflation, because they are not affected by consumers’ product preferences or price volatility as opposed to ad valorem taxes.

|

Source: Author’s definitions. |

|

| Product | Design |

|---|---|

| Vapor Products | Specific per milliliter |

| Snus | Specific per ounce |

| Nicotine Pouches | Specific per ounce |

| Heated tobacco | Specific per stick/pod |

Black Market Risks

Among the biggest risks when designing taxes for nicotine products is the creation of a black market. The risk of creating a new black market or fueling an existing one with operators willing and able to supply nicotine products to consumers is significant. Most vapor product users formerly smoked cigarettes.[40] With this in mind, it is safe to assume that the behaviors of vapers mirror those of smokers, when presented with the opportunity to reduce their tax payments. As the data from cigarettes clearly show, regional as well as global differences in taxation increase the inefficiency of local measures and the risk of illicit trade. Several states (see Figure 4) which already have rampant illicit trade risk losing complete control of their nicotine and tobacco market, as more consumers shift to the black market.[41]

Cigarettes are already being smuggled into and around the country in large quantities, and nicotine-containing liquid is coming into the U.S. from questionable sources.[42] On top of not contributing to state and federal revenue—costing governments billions in lost taxes—black market liquid and cigarettes have the added problem of being extremely unsafe. [43] The latest stories about serious pulmonary diseases have prompted the FDA to publish a warning about black market THC-containing liquid.[44] Reports of illicit products containing dangerous chemicals resulting in serious conditions have been released over the last months. [45]

On top of the dangers to consumers, the legal market would also suffer, as untaxed and unregulated products have significant competitive advantages over high-priced legal products. This would impact not only the large number of small business owners operating over 10,000 vape shops around the country, but also convenience stores and gas stations relying heavily on vapers as well as tobacco sales. Policymakers should not lose sight of the law of unintended consequences as they set rates and regulatory regimes for nicotine products.

Bans

Bans are an important consideration when it comes to designing tax policy because even the most principled tax structure risks accelerating black market activities if popular products are not available in the legal market Recently, the FDA has announced a ban on all pod-based flavors except menthol and tobacco, and there are active legislative proposals to ban all flavors except tobacco as well as banning certain types of product designs deemed to attract young people.

The Pigouvian concept of internalizing externalities to correct inefficient market outcomes suggests that the size of the excise tax should be equal to the negative externality. Under this framework, we can discuss a ban as an infinite tax: a tax so high that no market activity can take place.

A real-world observation can be made in some American cities, where the excise tax level on cigarettes is approaching de facto prohibition.[46]

Both in practice and in theory there is a problem with these bans. For instance, there is only a basis for a ban if the sale and use of the good always generates larger negative externality than positive externality. In this case, nicotine products are helping adult smokers quit cigarettes and switch to less harmful products. In other words, these bans are not optimal policy. In practice, adult users unwilling to quit nicotine will either find legal or illegal substitutes to the banned product.

Like the inefficiency of high narrow-base taxes, bans are likely to hurt public health by limiting adult smokers’ ability to quit cigarettes and fueling black market activity. The more local a ban is introduced, the higher the risk of black and grey market activity.

State-by-State

The following section lists different taxation design in states that tax both vapor products and snus. The focus is on vaping and snus as these products are the only tobacco and nicotine products that have independent claims for their potential in harm reduction.[47]

How states define snuff or snus differs slightly, but most define it as powdered, finely cut, or ground tobacco not intended to be smoked. Most states tax snus as smokeless tobacco.

Several states levy the regular sales tax in addition to the excise tax. The sales tax is not included below.

California

California taxes vapor products and other non-combustible tobacco products ad valorem at 59.27 percent of wholesale value under the Tobacco Products Tax statute.[48] The percentage is adjusted annually by the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration. The state taxes vaping as “other tobacco products” and the rate is supposed to be equivalent to the rate for cigarettes. Non-nicotine vape liquids are not subject to the Tobacco Products Tax. Devices are only taxed when sold bundled with nicotine-containing liquid. California generated $32 million in revenue in fiscal year 2018.[49]

Connecticut

Connecticut taxes prefilled vaping product a specific rate at $0.40 per milliliter under the Electronic Cigarette Product Tax statute.[50] Other products, devices included, are taxed at 10 percent of wholesale value. Connecticut does not tax non-nicotine-containing liquid. Connecticut’s tax took effect in October 2019, and no revenue data are available.

Snus is taxed at $3 per ounce.[51] Connecticut has implemented a “modified risk” clause in its tax code. Products with “modified risk tobacco product orders” according to 21 U.S.C. § 387k(g)(1) pay 50 percent less in excise taxes.[52]

Delaware

Delaware taxes vapor product a specific rate at $0.05 per milliliter of nicotine-containing liquid under the Tobacco Product Tax statute.[53] Snus is taxed at $0.92 per ounce.[54] No public revenue data are available.

Illinois

Illinois has a 15 percent ad valorem wholesale tax on vapor products. Devices and parts are also taxed if the products are designed for vaping.[55] Illinois taxes snus at $0.30 per ounce.[56] The tax only took effect in 2019, but Illinois expects to raise $15 million in fiscal year 2020.[57]

Kansas

Kansas taxes vape liquid at a specific rate of $0.05 per milliliter, with or without nicotine.[58] Non-combustible tobacco products including snus are taxed ad valorem at 10 percent wholesale price.[59] No public revenue figure is available, although the Kansas Legislative Research Department forecasted $2 million in the first year at a rate of $0.20 per milliliter.[60]

Louisiana

Louisiana taxes vape liquid at a specific rate of $0.05 per milliliter. The tax is only levied on nicotine-containing liquid. Snus is taxed at 20 percent of manufacturer price. Louisiana collected $1.8 million in the first two years of levying the tax between August 2015 and September 2017.[61]

Maine

The Maine legislature passed a tax of 43 percent of wholesale value on vaping products. The tax is levied on both devices and liquid and takes effect in January 2020.[62] The state taxes snus at $2.02 per ounce, with a minimum tax of $2.02.[63]

Massachusetts

Massachusetts passed a 75 percent wholesale tax in December 2019 in a bill that also bans most flavors for all tobacco and nicotine products. The tax will take effect June 1, 2020 and applies to both liquid and device.[64] Smokeless tobacco including snus is taxed at 210 percent of wholesale price.[65]

Minnesota

Minnesota is the state with the longest-running tax for e-cigarettes. It taxes vapor products ad valorem at 95 percent of the wholesale value as it considers it a non-cigarette smoking tobacco product. The rate is supposed to mirror the excise burden on cigarettes. In 2017 Minnesota raised $7 million from vapor products. A similar rate is imposed on snus up to 1.2 ounces. An equivalent tax is applied based on additional weight.[66]

Nevada

Nevada taxes vapor products at 30 percent of wholesale value. The product is treated like a tobacco product in the Nevada tax code. Both nicotine and non-nicotine products as well as components are subject to the tax and takes effect in January 2020.[67] A similar rate is levied on other non-combustible tobacco products such as snus.[68]

New Hampshire

New Hampshire has a bifurcated excise tax on vape products that takes effect in January 2020. The state taxes open tanks ad valorem at 8 percent of wholesale value. The tax for closed pods is $0.30 per milliliter.[69] Snus is taxed at 65.03 percent of wholesale price.[70]

New Jersey

New Jersey has a specific excise tax of $0.10 per milliliter on nicotine vape liquid sold as pods and cartridges. Bottled open tank liquid is taxed ad valorem at 10 percent of retail sale price.[71] Snus is taxed at $0.75 per ounce. The tax took effect November 1, 2019.[72]

New Mexico

New Mexico has a bifurcated excise tax on vape products. The state taxes open tanks ad valorem at 12.5 percent of wholesale value. The tax for closed pods with a capacity under 5 milliliters is $0.50.[73] The tax took effect in July 2019. Snus is taxed at 25 percent of manufacturer value.[74]

New York

New York taxes vape products ad valorem at 20 percent of retail price on all vapor products (not including devices), both with and without nicotine. The tax took effect in December 2019.[75] Snus is taxed at $2 per ounce with a minimum tax of $2.[76]

North Carolina

North Carolina, a state with a history of taxing vapor products, collected $4.5 million on vapor products and $260 million in total tobacco tax revenue in fiscal year 2018.[77] It taxes vapor products at $0.05 per milliliter and snus at 12.8 percent of wholesale value.[78].[79]

North Carolina has implemented a “modified risk” clause in its tax code. Products for which modified risk tobacco product orders are issued under 21 U.S.C. § 387k(g)(1) pay 50 percent less in excise taxes.[80]

Ohio

In Ohio, vape products are taxed ad valorem at $0.10 per milliliter. The tax only applies to nicotine-containing liquid. The tax took effect in October 2019.[81] Snus is taxed at 17 percent of wholesale value. [82]

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania has a 40 percent ad valorem tax of wholesale value on vapor products. The tax has been blamed for causing the closure of many small independent vape shops in the state. According to Pennsylvania’s Bureau of Trust Fund Taxes, enforcement of the tax has been very problematic due to the nature of the business. Many buy products from out of state and due to the complex nature of the reporting, many refused to report and pay the tax.[83] The state collected $17 million the first year the tax was in effect (October 2016 to September 2017).[84] Pennsylvania taxes snus at $0.55 per ounce.[85]

Vermont

Vermont has an ad valorem excise tax of 92 percent of wholesale value on both vape liquid (with or without nicotine) and devices. The tax took effect July 1, 2019.[86] The state taxes snus at $2.57 per ounce, but at a minimum of $3.08 per pack.[87]

Washington

Washington state has a bifurcated tax system, where open tanks greater than 5 milliliters are taxed at $0.09 per milliliter and closed pods at $0.27 per milliliter, with or without nicotine.[88] Snus is taxed at $2.526 per 1.2 ounce, at a minimum of $2.526.[89]

Washington has implemented a “modified risk” clause in its tax code. Products with “modified risk tobacco product orders” according to 21 U.S.C. § 387k(g)(1) pay 50 percent less in excise taxes.[90]

West Virginia

West Virginia taxes at a specific rate of $0.075 per milliliter, on products with or without nicotine.[91] West Virginia collected $1.6 million in the first 15 month of collections.[92] Snus is taxed at 12 percent of wholesale value.[93]

Wisconsin

Wisconsin taxes vapor liquid at a specific rate of $0.05 per milliliter on all liquids. The tax took effect in October 2019.[94] Snus is taxed ad valorem at 100 percent of manufacturer price.[95]

District of Columbia

The District of Columbia taxes all non-cigarette tobacco products ad valorem at 91 percent of wholesale value under the Tax on Other Tobacco Products statute.[96] The District taxes vaping devices at 96 percent. The device is also taxed. No public data is available on revenue from the tax as the numbers are bundled with other tobacco products.

|

Source: Bloomberg Tax, State Statutes |

||

| State | Snus | Vapor |

|---|---|---|

| California | 59.27% wholesale | 59.27% |

| Connecticut | $3 per oz. | $0.40 per ml. closed tanks

10% wholesale other vapor products |

| D.C. | 91% wholesale | 96% wholesale |

| Delaware | $0.92 per oz. | $0.05 per ml. |

| Illinois | $0.30 per oz. | 15% wholesale |

| Kansas | 10% wholesale | $0.05 per ml. |

| Louisiana | 20% manufacturer price | $0.05 per ml. |

| Maine | $2.02 per oz. | 43% wholesale |

| Massachusetts | 210% wholesale | 75% percent wholesale |

| Minnesota | 95% wholesale | 95% wholesale |

| Nevada | 30% wholesale | 30% wholesale |

| New Hampshire | 65.03% wholesale | $0.30 per ml. closed tanks

8% wholesale open tanks |

| New Jersey | $0.75 per oz. | $0.10 per ml. closed tanks

10% retail open tanks |

| New Mexico | 25% manufacturer price | $0.50 closed tanks

12.5% wholesale open tanks |

| New York | $2 per oz. | 20% retail |

| North Carolina | 12.8% wholesale | $0.05 per ml. |

| Ohio | 17% wholesale | $0.10 per ml. |

| Pennsylvania | $0.55 per oz. | 40% wholesale |

| Vermont | $2.57 per oz. Minimum $3.08 per can | 92% wholesale |

| Washington | $2.526 per 1.2 oz. | $0.09 per ml. open tanks

$0.27 per ml. closed tanks |

| West Virginia | 12% wholesale | $0.075 per ml. |

| Wisconsin | 100% manufactures price | $0.05 per ml. |

Conclusion

The introduction of electronic nicotine delivery systems has dramatically changed the nicotine market in America over the last decade. Declining revenues from taxes on traditional tobacco products have created a political need to find new sources of revenue. A popular solution is to extend “sin taxes” to new products. Though excise taxes on tobacco has historically been a revenue source, another rationale for taxing the product has been public health concerns. Used this way excise taxes are applied to price in externalities that the market price does not reflect and to deter use.

In 2019, several federal lawmakers have called for a federal tax on vapor products. There are two Senate bills and one House bill aiming to introduce a vapor products excise tax at the level applied to cigarettes. All states tax tobacco products, but only 21 states and the District of Columbia tax vapor products. Currently three designs are utilized at state level: pure ad valorem, pure specific, or a bifurcated system for open and closed tanks. More states will likely pass tax bills on vapor products in 2020.

If the main consideration is public health, taxation of nicotine products could be counterproductive as there is consensus about the benefits of smokers substitutes for non-combustible nicotine or tobacco products. However, if lawmakers decide to tax these products, they should design a principled excise regime. Legislators should focus on raising revenue in a simple, neutral, transparent, and stable manner. Levying taxes based on these principles limits the adverse effects on the economy and the individual.

A specific excise tax at a low rate is the most efficient way to design a tax on nicotine products as it allows smokers to substitute less harmful products for cigarettes. Lawmakers should keep spillover effects in mind, because taxes on nicotine products reduces the effectiveness of excise taxes on traditional cigarettes. Taxing nicotine products with similar qualities at similar rates regardless of design is another important consideration. Volume and weight-based tax design makes this easier as well as more transparent for consumers and businesses. Finally, the tax collections should be worthwhile relative to the burdens placed on consumers and businesses.

With both state and federal legislatures poised to introduce new taxes and bans, access to harm-reducing products is in the balance for adult smokers. Policymakers would do well to consider the potential of these products in combating smoking of combustible tobacco products before supporting punitive taxes or bans.

[1] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States,” Nov. 18, 2019, https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/index.htm.

[2] Bonnie Herzog, “Wall Street Tobacco Industry Update,” Wells Fargo, Feb. 11, 2019, 3, http://www.natocentral.org/uploads/Wall_Street_Update_Slide_Deck_February_2019.pdf.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Frank Newport, “Young People Adopt Vaping as Their Smoking Rate Plummets,” Gallup, July 26, 2018, https://news.gallup.com/poll/237818/young-people-adopt-vaping-smoking-rate-plummets.aspx.

[6] U.S. Food & Drug Administration, “FDA grants first-ever modified risk orders to eight smokeless tobacco products,” Oct. 22, 2019, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-grants-first-ever-modified-risk-orders-eight-smokeless-tobacco-products.

[7] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Smokeless Tobacco Use in the United States,” Aug. 29, 2018, https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/smokeless/use_us/index.htm.

[8] Colm Fulton, “Swedish Match profits boosted by sales of tobacco-free pouches,” Reuters, Oct. 25, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-swedish-match-results/swedish-match-profits-boosted-by-sales-of-tobacco-free-pouches-idUSKBN1X41A4.

[9] See Joel L. Nitzkin, “The Case in Favor of E-Cigarettes for Tobacco Harm Reduction,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11:6 (June 2014), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4078589/; and Pasquale Caponnetto, Davide Campagna, Fabio Cibella, Jaymin B. Morjaria, Massimo Caruso, Cristina Russo, and Riccardo Polosa, “EffiCiency and Safety of an eLectronic cigAreTte (ECLAT) as Tobacco Cigarettes Substitute: A Prospective 12-Month Randomized Control Design Study,” PLOS One, June 24, 2013, http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0066317.

[10] Madeline Kennedy, “Cigarette smoking costs weigh heavily on the healthcare system,” Reuters, Dec. 19, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-healthcare-costs-smoking-idUSKBN0JX2BE20141219.

[11] Michael Cooper, “Cigarettes Up To $7 a Pack With New Tax,” The New York Times, July 1, 2002, https://www.nytimes.com/2002/07/01/nyregion/cigarettes-up-to-7-a-pack-with-new-tax.html.

[12] Congressional Budget Office, “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2019 to 2029,” January 2019, 91, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files?file=2019-01/54918-Outlook-Chapter4.pdf.

[13] United States Census Bureau, “2018 State Government Tax Tables,” June 11, 2019, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2018/econ/stc/2018-annual.html.

[14] IRS, “SOI Tax Stats – Excise Tax Statistics,” Dec. 3, 2019, https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-excise-tax-statistics.

[15] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Cigarette Smoking and Tobacco Use Among People of Low Socioeconomic Status,” Mar. 7, 2018, https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/disparities/low-ses/index.htm.

[16] Heated tobacco is taxed at the federal level, as it is a tobacco product.

[17] S.2463 – “E-Cigarette Tax Parity Act,” 116th Congress (2019-2020), https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/2463/text?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22e-cigarettes%22%5D%7D&r=4&s=2.

[18] S.2519 – “ENND Act,” 116th Congress (2019-2020), https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/2519/text?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22e-cigarettes%22%5D%7D&r=12&s=2.

[19] “Amendment in the Nature of a Substitute to H.R. 4742,” U.S. House of Representatives, Oct.21, 2019, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/WM/WM00/20191023/110145/BILLS-116HR4742ih.pdf.

[20] Vapors and smokers can compensate for lower nicotine content by increasing the number of drags or the strength of drags.

[21] See State-by-State section.

[22] VA § 58.1-1021.01 – “Code of Virginia, Article 2.1. Tobacco Products Tax, Definitions,” https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacodefull/title58.1/chapter10/article2.1/.

[23] Bureau of Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of Public Health, “Health Impacts and Taxation of Electronic Cigarettes,” Louisiana Department of Health, January 2018, 62, http://ldh.la.gov/assets/docs/LegisReports/HR155RS2017ecigarettes12018.pdf.

[24] Ibid., 63.

[25] Justine Mcdaniel, “Vape tax brings in millions – and is said to close over 100 Pa. businesses,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, Sept. 5, 2017, https://www.inquirer.com/philly/news/pennsylvania/vape-tax-brings-in-millions-and-closes-over-100-pa-businesses-20170905.html.

[26] U.S. Food and Drug Administration, “FDA grants first-ever modified risk orders to eight smokeless tobacco products.”

[27] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States.” .

[28] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Quitting Smoking,” https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/cessation/quitting/index.htm.

[29] Truth Initiative, “What you need to know to quit smoking,” Nov. 7, 2018, https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/quitting-smoking-vaping/what-you-need-know-quit-smoking.

[30] Public Health England, “ E-cigarettes around 95% less harmful than tobacco estimates landmark review,” Aug. 19, 2015, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/e-cigarettes-around-95-less-harmful-than-tobacco-estimates-landmark-review.

[31] Michael F. Pesko, Charles J. Courtemanche, and Johanna Catherine Maclean, “The Effects Of Traditional Cigarette And E-Cigarette Taxes On Adult Tobacco Product Use,” National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2019, https://www.nber.org/papers/w26017.

[32] Henry Saffer, Daniel L. Dench, Michael Grossman, and Dhaval M. Dave, “E-Cigarettes and Adult Smoking: Evidence from Minnesota,” National Bureau of Economic Research, December 2019, https://www.nber.org/papers/w26589.

[33] Victoria R. Green, “FDA Regulation of Tobacco Products,” Congressional Research Service, Aug. 13, 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R45867.pdf.

[34] Justin M. Ross, “A PRIMER ON STATE AND LOCAL TAX POLICY: Trade-Offs among Tax Instruments,” Mercatus Center, George Mason University, Feb. 25, 2014, 5, https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/Ross_PrimerTaxPolicy_v2.pdf.

[35] The Tax Foundation generally encourages specific excise taxes at reasonable rates, when lawmakers decide to tax a certain good. The one outlier is marijuana taxes, where a lack of data as well as market immaturity have made it difficult to determine the optimal tax structure.

[36] Leon Kośmider, Catherine F. Kimber, Jolanta Kurek, Olivia Corcoran, and Lynne E. Dawkins, “Compensatory Puffing With Lower Nicotine Concentration E-liquids Increases Carbonyl Exposure in E-cigarette Aerosols, Nicotine & Tobacco Research 20:8 (August 2018), 998-1003, https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntx162.

[37] Michael F. Pesko, Charles J. Courtemanche, and Johanna Catherine Maclean, “The Effects Of Traditional Cigarette And E-Cigarette Taxes On Adult Tobacco Product Use, 22.

[38] Erica York and Alex Muresianu, “Reviewing Different Methods of Calculating Tax Compliance Costs,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 21, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/different-methods-calculating-tax-compliance-costs/.

[39] There is no available data specifically for snus as it is taxed within the smokeless tobacco category, and nicotine pouches are not subject to any excise tax yet.

[40] Truth Initiative, “E-cigarettes: Facts, stats and regulations,” Nov. 11, 2019, https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/emerging-tobacco-products/e-cigarettes-facts-stats-and-regulations.

[41] Ulrik Boesen, “Cigarette Taxes and Cigarette Smuggling by State, 2017,” Tax Foundation, Dec., 4, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/cigarette-taxes-and-cigarette-smuggling-by-state-2017/.

[42] Julie Bosman and Matt Richtel, “Vaping Bad: Were 2 Wisconsin Brothers the Walter Whites of THC Oils?” The New York Times, Sept. 17, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/15/health/vaping-thc-wisconsin.html.

[43] National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, Understanding the U.S. Illicit Tobacco Market: Characteristics, Policy Context, and Lessons from International Experiences (Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2015), https://doi.org/10.17226/19016.

[44] U.S. Food and Drug Administration, “Vaping Illness Update: FDA Warns Public to Stop Using Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-Containing Vaping Products and Any Vaping Products Obtained Off the Street,” Oct. 4, 2019, https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/vaping-illnesses-consumers-can-help-protect-themselves-avoiding-tetrahydrocannabinol-thc-containing.

[45] David Downs, Dave Howard, and Bruce Barcott, “Journey of a tainted vape cartridge: from China’s labs to your lungs,” Leafly, Sept. 24, 2019, https://www.leafly.com/news/politics/vape-pen-injury-supply-chain-investigation-leafly; and Conor Ferguson, Cynthia McFadden, Shanshan Dong, and Rich Schapiro, “Tests show bootleg marijuana vapes tainted with hydrogen cyanide,” NBC News, Sept. 27, 2019, https://www.nbcnews.com/health/vaping/tests-show-bootleg-marijuana-vapes-tainted-hydrogen-cyanide-n1059356.

[46] Ulrik Boesen, “Cigarette Taxes and Cigarette Smuggling by State, 2017.”

[47] Heated tobacco taxation is not mentioned as it a completely new product, which isn’t available nationwide.

[48] California Department of Tax and Fee Administration, “Tax Guide for Cigarettes and Tobacco Products,” http://www.cdtfa.ca.gov/industry/cigarette-and-tobacco-products.htm#Overview.

[49] Bureau of Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Office of Public Health, “Health Impacts and Taxation of Electronic cigarettes.”

[50] State Of Connecticut Department of Revenue Services, “Electronic Cigarette Products Tax,” Sept. 4, 2019, https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/DRS/Publications/pubssn/2019/SN-2019(7).pdf?la=en.

[51] See note 10.

[52] RCW 82.26.020.

[53] State of Delaware, “Title 30: State Taxes, Commodity Taxes, CHAPTER 53, Tobacco Product Tax, Subchapter II, Levy and Collection of Tax; License, Stamps,” https://delcode.delaware.gov/title30/c053/sc02/index.shtml.

[54] Del. Code Ann. tit. 30, § 5305(c)(2).

[55] Illinois Department of Revenue, “Electronic Cigarettes FAQ,” https://www2.illinois.gov/rev/research/taxinformation/excise/Pages/Electronic_Cig_FAQ.aspx.

[56] See note 10.

[57] Stateline, “Amid Vaping Craze, States Push Hefty Taxes ,“ Governing.com, Aug. 19, 2019, https://www.governing.com/topics/finance/sl-state-taxes-vaping.html.

[58] Kansas Office of Revisor of States, “79-3399. Tax on electronic cigarettes imposed; rates; inventory tax,” https://www.ksrevisor.org/statutes/chapters/ch79/079_033_0099.html.

[59] Kansas Department Of Revenue, “Chapter 79—TAXATION, Article 33—Cigarette and Tobacco Products,” https://www.ksrevenue.org/pdf/CigTobaccotaxLawsRegs.pdf.

[60] Mark Dapp, “Kansas Legislator Briefing Book 2018: Taxation, J-1, E-cigarettes or ‘E-cigs,’” Kansas Legislative Research Department, http://www.kslegresearch.org/KLRD-web/Publications/BriefingBook/2018Briefs/J-1-ElectronicCigarettesorE-cigs.pdf.

[61] See notes 20, 56.

[62] Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 36, § 4401(9).

[63] Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 36-4403(1).

[64] Mass.gov, “2019 Tobacco Control Law,” https://www.mass.gov/guides/2019-tobacco-control-law#-new-tobacco-control-law-.

[65] Mass.gov, “DOR Cigarette and Tobacco Excise Tax,” https://www.mass.gov/info-details/dor-cigarette-and-tobacco-excise-tax.

[66] Minn. Stat. § 297F.05.

[67] Nev. Rev. Stat. tit. 32 § 370.450(1).

[68] Ibid.

[69] N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 78:2(II)(b).

[70] N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 78:2(II).

[71] N.J. Rev. Stat. § 54:40B-3.2.

[72] N.J. Rev. Stat. § 54:40B-3(a)(1).

[73] N.M. Stat. Ann. § 7-12A-3(A).

[74] N.M. Stat. Ann. § 7-12A-3(A).

[75] N.Y. Tax Law § 1181.

[76] N.Y. Tax Law § 471-b(1)(c).

[77] NC Financial Services Division, Revenue Research Section, “Statistical Abstract of North Carolina Taxes 2018,” https://files.nc.gov/ncdor/documents/reports/advanceabstract_2018.pdf.

[78] N.C. Gen. Stat. § 105-113.35(a1).

[79] N.C. Gen. Stat. § 105-113.35A.

[80] N.C. Gen. Stat. § 105-113.4E.

[81] Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 5743.51(A)(4).

[82] Ibid.

[83] Bureau of Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Office of Public Health, “Health Impacts and Taxation of Electronic Cigarettes,” 32.

[84] Ibid.

[85] 72. Pa. Stat. § 8202-A.

[86] Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 32, § 7811.

[87] Ibid.

[88] Washington State Department of Revenue, “Vapor products tax,” https://dor.wa.gov/find-taxes-rates/other-taxes/vapor-products-tax.

[89] Wash. Rev. Code § 82.26.020(1).

[90] RCW 82.26.020.

[91] W. Va. Code § 11-17-4b(b).

[92] Bureau of Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Office of Public Health,“Health Impacts and Taxation of Electronic Cigarettes” Louisiana Department of Health,” 55.

[93] W. Va. Code § 11-17-3(b).

[94] Wis. Stat. § 139.76(1m): Wis. Stat. § 139.75(14).

[95] Wis. Stat. § 139.76.

[96] Code of the District of Columbia, § 47–2402.01, “Tax on other tobacco products,” https://code.dccouncil.us/dc/council/code/sections/47-2402.01.html.

Source: Tax Policy – Taxing Nicotine Products: A Primer