Tax Policy – State Corporate Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2020

Key Findings

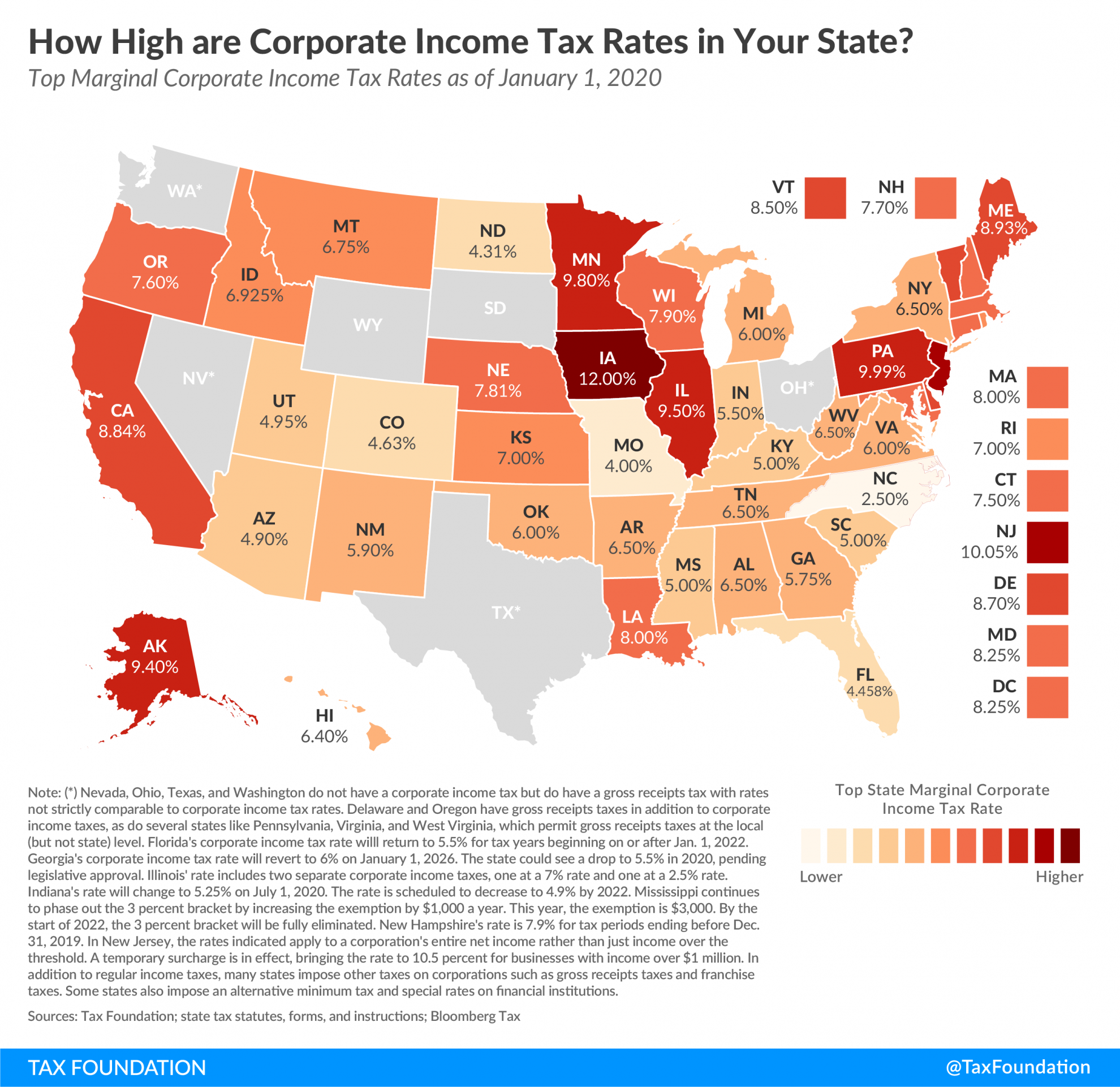

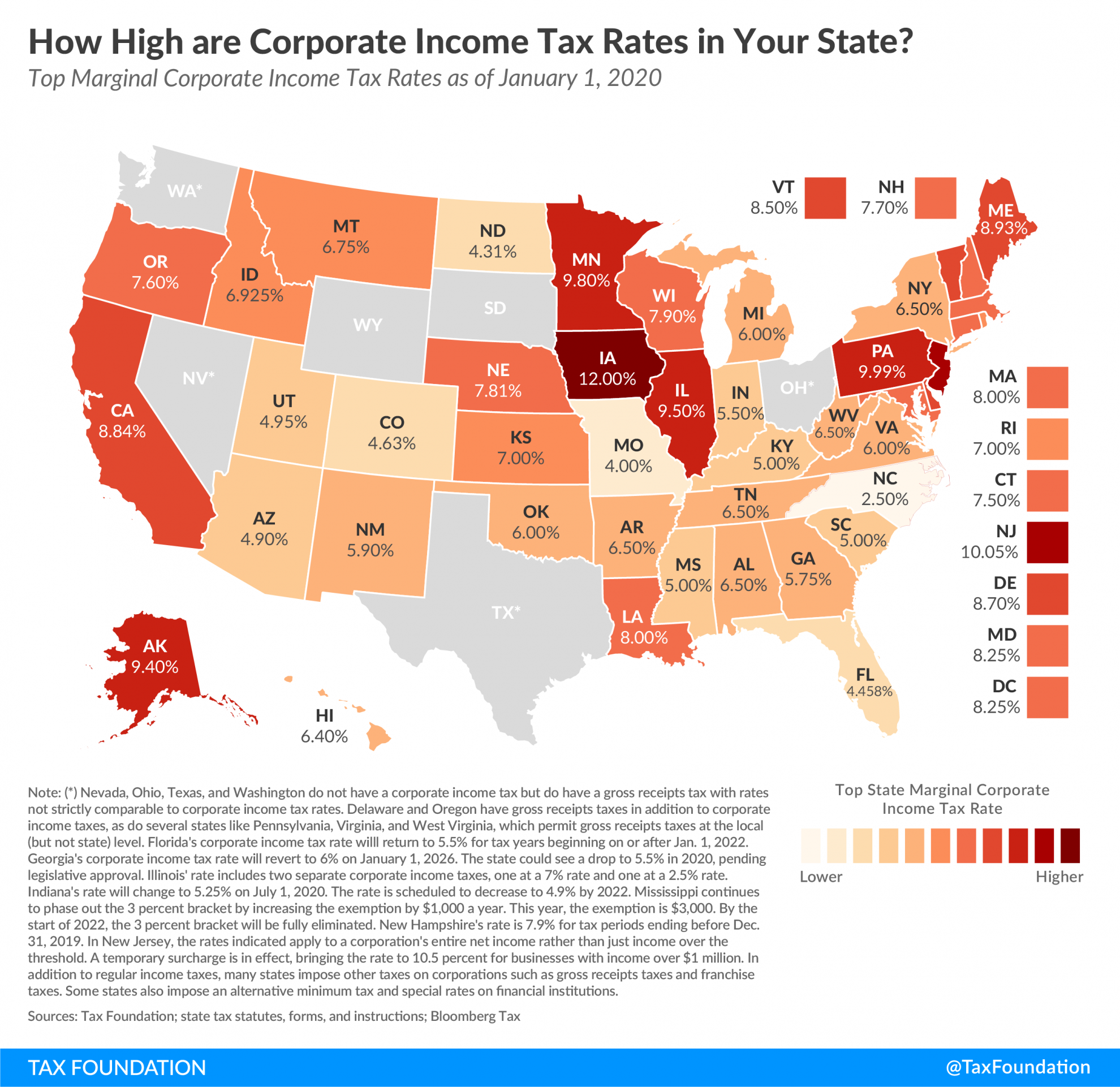

- Forty-four states levy a corporate income tax. Rates range from 2.5 percent in North Carolina to 12 percent in Iowa.

- Six states—Alaska, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania—levy top marginal corporate income tax rates of 9 percent or higher.

- Ten states—Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, North Dakota, South Carolina, and Utah—have top rates at or below 5 percent.

- Nevada, Ohio, Texas, and Washington impose gross receipts taxes instead of corporate income taxes. Gross receipts taxes are generally thought to be more economically harmful than corporate income taxes.

- South Dakota and Wyoming are the only states that do not levy a corporate income or gross receipts tax.

Corporate income taxes are levied in 44 states. Though often thought of as a major tax type, corporate income taxes account for an average of just 4.73 percent of state tax collections and 2.27 percent of state general revenue.[1]

Iowa levies the highest top statutory corporate tax rate at 12 percent,[2] followed by New Jersey (10.5 percent), Pennsylvania (9.99 percent), and Minnesota (9.8 percent). Two other states (Alaska and Illinois) levy rates of 9 percent or higher.

Conversely, North Carolina’s flat rate of 2.5 percent is the lowest in the country, followed by rates in Missouri (4 percent) and North Dakota (4.31 percent). Seven other states impose top rates at or below 5 percent: Florida (4.458 percent), Colorado (4.63 percent), Arizona (4.9 percent), Utah (4.95 percent), and Kentucky, Mississippi, and South Carolina (5 percent).

Nevada, Ohio, Texas, and Washington forgo corporate income taxes but instead impose gross receipts taxes on businesses, which are generally thought to be more economically harmful due to tax pyramiding and nontransparency.[3] Delaware and Oregon impose gross receipts taxes in addition to corporate income taxes, as do several states, like Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia, which permit gross receipts taxes at the local (but not state) level. South Dakota and Wyoming levy neither corporate income nor gross receipts taxes.

Thirty states and the District of Columbia have single-rate corporate tax systems. The greater propensity toward single-rate systems for corporate tax than individual income tax is likely because there is no meaningful “ability to pay” concept in corporate taxation. Jeffrey Kwall, professor of law at Loyola University Chicago School of Law, notes that:

Graduated corporate rates are inequitable—that is, the size of a corporation bears no necessary relation to the income levels of the owners. Indeed, low-income corporations may be owned by individuals with high incomes, and high-income corporations may be owned by individuals with low incomes.[4]

A single-rate system minimizes the incentive for firms to engage in economically wasteful tax planning to mitigate the damage of higher marginal tax rates that some states levy as taxable income rises.

Notable Corporate Income Tax Changes in 2020

Several states implemented corporate income tax rate changes over the past year, among other revisions and reforms. Notable changes for 2020 include:

- Florida’s corporate income tax rates were set to revert to the 2018 rate of 5.5 percent, but legislation was enacted to extend the 2019 rate of 4.458 percent to 2020 and 2021.[5]

- As part of a 2018 tax cut package following federal reform, Georgia lowered its top corporate income tax rate from 6 percent to 5.75 percent and doubled the standard deduction.[6] A further reduction to 5.5 percent is scheduled for 2020, pending legislative approval.

- Indiana’s rate decreased to 5.5 percent on July 1, 2019, and a further reduction to 5.25 percent is scheduled to kick in July 1, 2020.[7]

- Mississippi continued phasing out its 3 percent corporate income tax bracket by exempting the first $3,000 of income this year. The 4 and 5 percent brackets remain in place.[8]

- Missouri lowered its corporate income tax rate from 6.25 to 4 percent, paying down this reduction by no longer giving companies the option of choosing the apportionment formula most favorable to them.[9]

- New Jersey’s temporary surcharge decreased from 2.5 to 1.5 percent, bringing the state’s top rate to 10.5 percent instead of 11.5 percent.

| State | Rates | Brackets | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ala. | 6.5% | > | $0 |

| Alaska | 0.0% | > | $0 |

| 2.0% | > | $25,000 | |

| 3.0% | > | $49,000 | |

| 4.0% | > | $74,000 | |

| 5.0% | > | $99,000 | |

| 6.0% | > | $124,000 | |

| 7.0% | > | $148,000 | |

| 8.0% | > | $173,000 | |

| 9.0% | > | $198,000 | |

| 9.4% | > | $222,000 | |

| Ariz. | 4.9% | > | $0 |

| Ark. | 1.0% | > | $0 |

| 2.0% | > | $3,000 | |

| 3.0% | > | $6,000 | |

| 5.0% | > | $11,000 | |

| 6.0% | > | $25,000 | |

| 6.5% | > | $100,000 | |

| Calif. | 8.84% | > | $0 |

| Colo. | 4.63% | > | $0 |

| Conn. | 7.5% | > | $0 |

| Del. (a) | 8.7% | > | $0 |

| Fla. | 4.458% | > | $0 |

| Ga. (c) | 5.75% | > | $0 |

| Hawaii | 4.4% | > | $0 |

| 5.4% | > | $25,000 | |

| 6.4% | > | $100,000 | |

| Idaho | 6.925% | > | $0 |

| Ill. (d) | 9.5% | > | $0 |

| Ind. (e) | 5.50% | > | $0 |

| Iowa | 6% | > | $0 |

| 8% | > | $25,000 | |

| 10% | > | $100,000 | |

| 12% | > | $250,000 | |

| Kans. | 4% | > | $0 |

| 7% | > | $50,000 | |

| Ky. | 5% | > | $0 |

| La. | 4% | > | $0 |

| 5% | > | $25,000 | |

| 6% | > | $50,000 | |

| 7% | > | $100,000 | |

| 8% | > | $200,000 | |

| Maine | 3.50% | > | $0 |

| 7.93% | > | $350,000 | |

| 8.33% | > | $1,050,000 | |

| 8.93% | > | $3,500,000 | |

| Md. | 8.25% | > | $0 |

| Mass. | 8% | > | $0 |

| Mich. | 6% | > | $0 |

| Minn. | 9.8% | > | $0 |

| Miss. (f) | 3% | > | $0 |

| 4% | > | $5,000 | |

| 5% | > | $10,000 | |

| Mo. | 4.00% | > | $0 |

| Mont. | 6.75% | > | $0 |

| Nebr. | 5.58% | > | $0 |

| 7.81% | > | $100,000 | |

| Nev. | (a) | ||

| N.H. (g) | 7.7% | > | $0 |

| N.J. (h) | 6.5% | > | $0 |

| 7.5% | > | $50,000 | |

| 9.0% | > | $100,000 | |

| 10.5% | > | $1,000,000 | |

| N.M. | 4.8% | > | $0 |

| 5.9% | > | $500,000 | |

| N.Y. | 6.5% | > | $0 |

| N.C. | 2.5% | > | $0 |

| N.D. | 1.41% | > | $0 |

| 3.55% | > | $25,000 | |

| 4.31% | > | $50,000 | |

| Ohio | (a) | ||

| Okla. | 6% | > | $0 |

| Ore. (a) | 6.6% | > | $0 |

| 7.6% | > | $1,000,000 | |

| Pa. | 9.99% | > | $0 |

| R.I. | 7% | > | $0 |

| S.C. | 5% | > | $0 |

| S.D. | None | ||

| Tenn. | 6.5% | > | $0 |

| Tex. | (a) | ||

| Utah | 4.95% | > | $0 |

| Vt. | 6.0% | > | $0 |

| 7.0% | > | $10,000 | |

| 8.5% | > | $25,000 | |

| Va. (a) | 6% | > | $0 |

| Wash. | (a) | ||

| W.Va. | 6.5% | > | $0 |

| Wis. | 7.9% | > | $0 |

| Wyo. | None | ||

| D.C. | 8.25% | > | $0 |

| (a) Nevada, Ohio, Texas, and Washington do not have a corporate income tax but do have a gross receipts tax with rates not strictly comparable to corporate income tax rates. See Table 18 for more information. Delaware and Oregon have gross receipts taxes in addition to corporate income taxes, as do several states like Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia, which permit gross receipts taxes at the local (but not state) level. | |||

| (b) Florida’s corporate income tax rate willl return to 5.5% for tax years beginning on or after Jan. 1, 2022. | |||

| (c) Georgia’s corporate income tax rate will revert to 6% on January 1, 2026. The state could see a drop to 5.5% in 2020, pending legislative approval. | |||

| (d) Illinois’ rate includes two separate corporate income taxes, one at a 7% rate and one at a 2.5% rate. | |||

| (e) Indiana’s rate will change to 5.25% on July 1, 2020. The rate is scheduled to decrease to 4.9% by 2022. | |||

| (f) Mississippi continues to phase out the 3 percent bracket by increasing the exemption by $1,000 a year. This year, the exemption is $3,000. By the start of 2022, the 3 percent bracket will be fully eliminated. | |||

| (g) New Hampshire’s rate is 7.9% for tax periods ending before Dec. 31, 2019. | |||

| (h) In New Jersey, the rates indicated apply to a corporation’s entire net income rather than just income over the threshold. A temporary surcharge is in effect, bringing the rate to 10.5 percent for businesses with income over $1 million. | |||

| Note: In addition to regular income taxes, many states impose other taxes on corporations such as gross receipts taxes and franchise taxes. Some states also impose an alternative minimum tax and special rates on financial institutions | |||

| Source: Tax Foundation; state tax statutes, forms, and instructions; Bloomberg Tax | |||

[1] U.S. Census Bureau, “2017 State & Local Government Finance Historical Datasets and Tables,” https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/2017/econ/local/public-use-datasets.html.

[2] Although Iowa has the highest top marginal corporate income tax in the nation, its rates are not directly comparable with those of other states because the state provides a deduction for federal taxes paid.

[3] Justin Ross, “Gross Receipts Taxes: Theory and Recent Evidence,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 6, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/gross-receipts-taxes-theory-and-recent-evidence/.

[4] Jeffrey L. Kwall, “The Repeal of Graduated Corporate Tax Rates,” Tax Notes, June 27, 2011, 1395.

[5] Katherine Loughead, “State Tax Changes as of January 1, 2020,” Dec. 20, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/2020-state-tax-changes-january-1/.

[6] Katherine Loughead, “Five States Accomplish Meaningful Tax Reform in the Wake of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Tax Foundation, July 23, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/five-states-accomplish-meaningful-tax-reform-wake-tax-cuts-jobs-act/.

[7] Scott Drenkard, “Indiana’s 2014 Tax Package Continues State’s Pattern of Year-Over-Year Improvements,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 7, 2014, https://taxfoundation.org/indiana-s-2014-tax-package-continues-state-s-pattern-year-over-year-improvements/.

[8] Joseph Bishop-Henchman, “Mississippi Approves Franchise Tax Phasedown, Income Tax Cut,” Tax Foundation, May 16, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/mississippi-approves-franchise-tax-phasedown-income-tax-cut/.

[9] Katherine Loughead, “State Tax Changes as of January 1, 2020.”

Source: Tax Policy – State Corporate Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2020