Tax Policy – FAQ on Digital Services Taxes and the OECD’s BEPS Project

Questions

- What is a digital services tax?

- What is the EU digital tax proposal?

- What is France’s digital tax proposal?

- What is the UK’s digital tax proposal?

- What countries have announced, proposed, or implemented a DST?

- What are some of the criticisms of a DST?

- What are alternatives to a DST?

- Why has the U.S. responded with tariffs to digital services taxes in Europe?

- How do digital services taxes relate to the OECD’s work on the taxation of the digital economy?

- Would an agreement on the taxation of the digital economy at the OECD level, if approved, take precedence over an individual country’s digital services tax (i.e., France)?

- What is the OECD BEPS project and what is its main objective?

- What is the main objective of OECD Pillar 1?

- What is the main objective of OECD Pillar 2?

What is a digital services tax?

A DST is a tax on selected gross revenue streams of large digital companies. Each country’s proposed or implemented DST differs slightly. For example, France applies a 3 percent tax on revenues from targeted advertising, the transmission of data collected about users for advertising purposes, and from providing a digital interface. All DSTs have domestic and global revenue thresholds, below which companies are not subject to the tax. Back to top

What is the EU digital tax proposal?

The European Commission proposed a turnover tax at a rate of 3 percent on revenues derived from online advertising services, online marketplaces, and sales of user collected data. Businesses with annual worldwide revenues of €750 million (US $868 million) and total EU revenues of €50 million ($58 million) would be subject to the tax.

The DST was proposed as an interim measure until the EU reforms its common corporate tax rules for digital activities. However, the proposal was laid aside in early 2019 because several EU member states opposed the tax. The new European Commission has announced that if the OECD does not reach an international agreement on the taxation of the digital economy in 2020, it will restart its work on the DST. Back to top

What is France’s digital tax proposal?

Similar to the EU proposal, France’s DST is levied at a rate of 3 percent and applies to online marketplaces and online advertising services (including the sale of user data in connection with internet advertising). The tax was adopted in July 2019 but is retroactive to January 1, 2019. Tax payments have been postponed by one year due to a threatened tariff by the United States. Tax liability, however, continues to accrue.

The French government was a strong proponent of the European Union’s DST. According to the French government, the French DST is a temporary measure until an international agreement on the taxation of the digital economy is reached. However, the tax law does not include a sunset clause that would repeal the tax at a set time in the future. Back to top

What is the UK’s digital tax proposal?

The UK proposed a 2 percent tax on revenues from search engines, social media platforms, and online marketplaces. The revenue thresholds are set at £500 million ($638 million) globally and £25 million ($32 million) domestically. The first £25 million in revenues would be exempt.

The tax is scheduled to go into effect in April 2020. Although the government stated that the tax would be a temporary measure until an international agreement on the taxation of the digital economy is reached, the draft legislation does not include a sunset clause (only a review of the DST before the end of 2025). Back to top

What countries have announced, proposed, or implemented a DST?

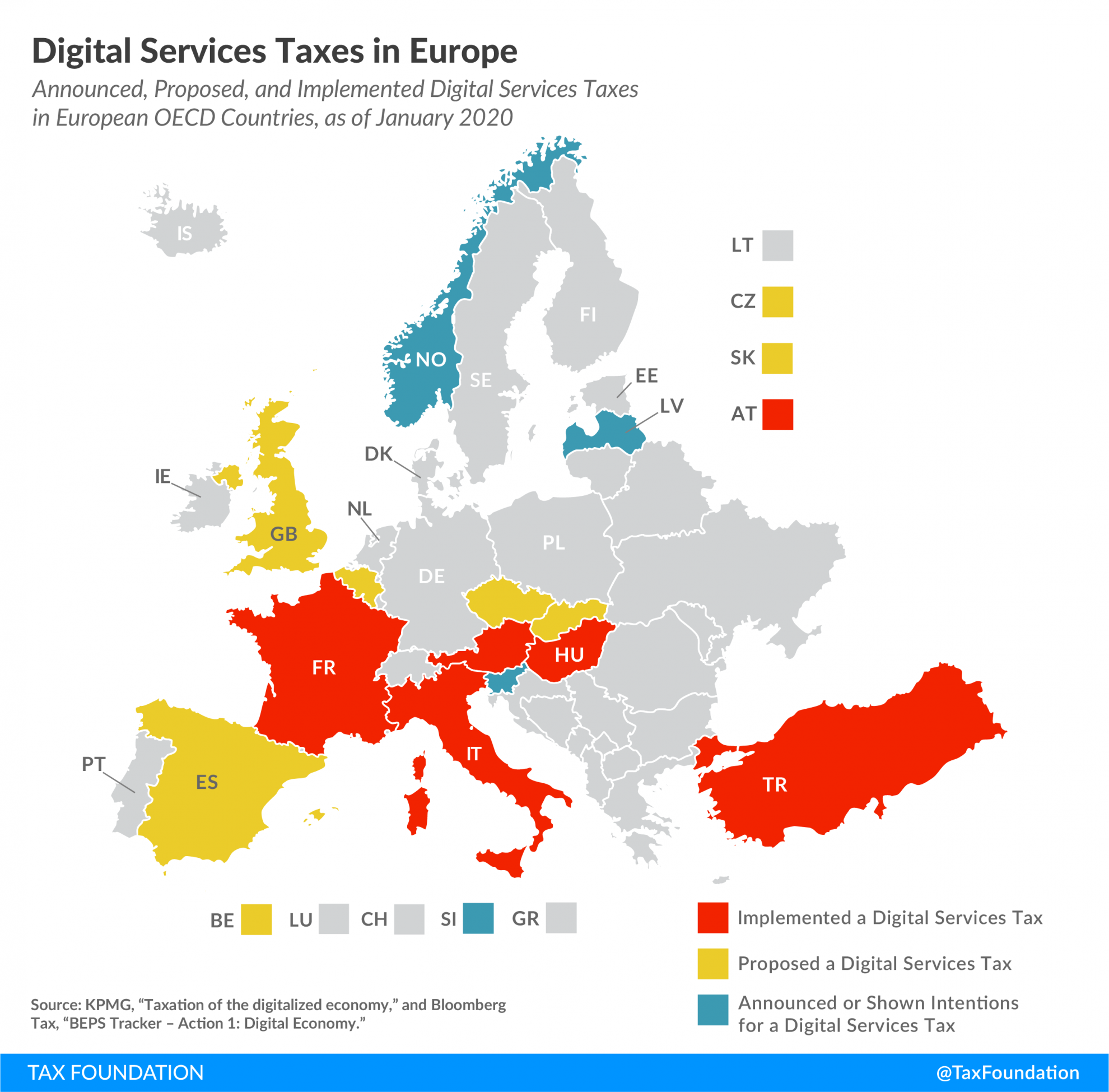

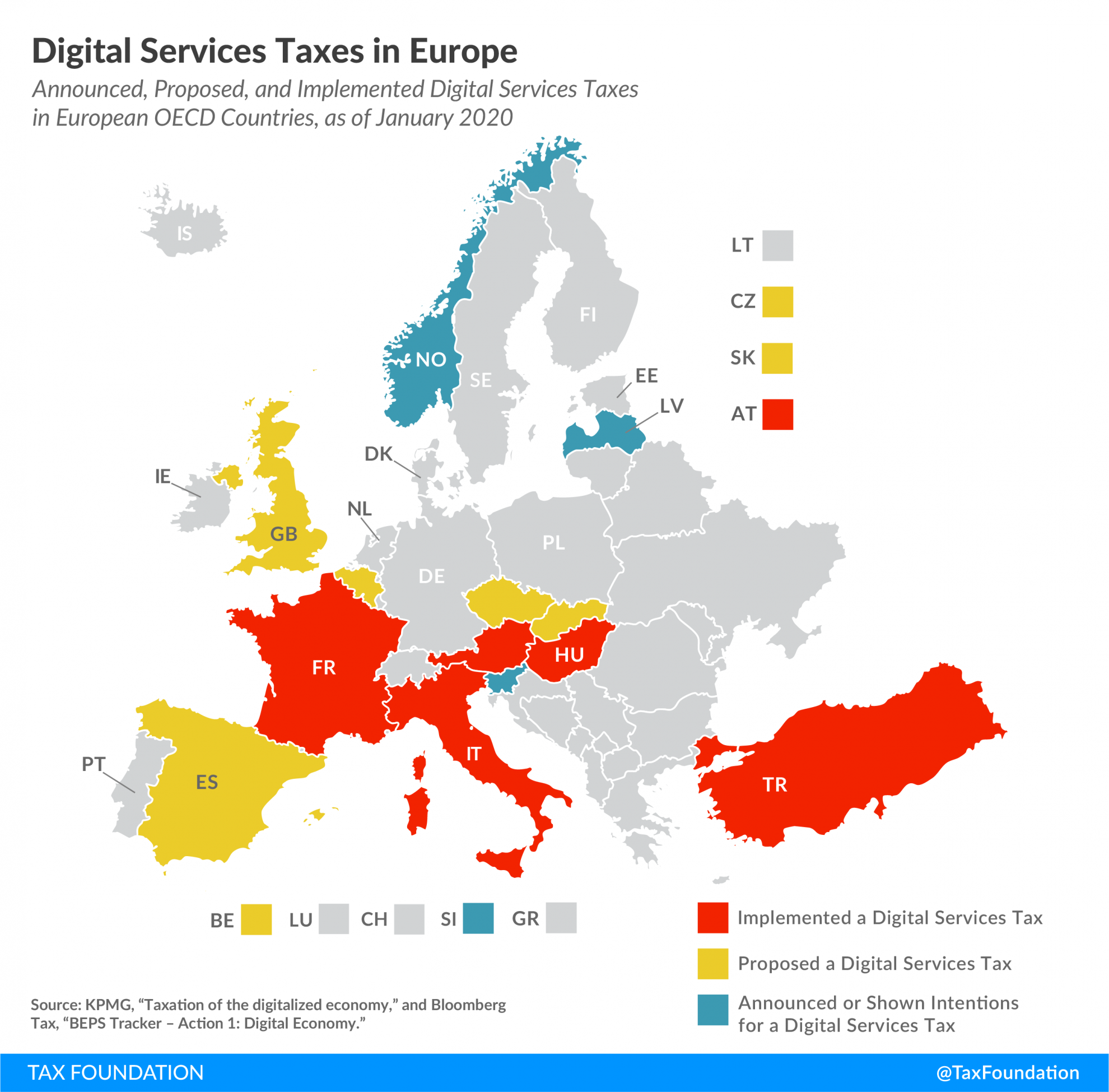

Among European OECD countries, Austria, France, Hungary, Italy, and Turkey have implemented a DST. Belgium, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Spain, and the United Kingdom have published proposals to enact a DST, and Latvia, Norway, and Slovenia have either officially announced or shown intentions to implement such a tax. Poland recently suspended its work on the digital services tax (as of January 2020).

You can find an overview of all European OECD countries’ DSTs here.

Outside of Europe, countries that have announced a DST include Canada and Israel. Back to top

What are some of the criticisms of a DST?

DSTs are structured as a turnover tax, meaning they tax gross revenues rather than net income. This design can lead to high marginal tax rates on businesses that are less profitable. Historically, turnover taxes have been rejected as poor tax policy because they are inefficient, create barriers to economic growth, and generally are considered unfair tax policy.

Tax policy designed to target a single sector or activity is likely to be unfair and have complex consequences. The digital economy cannot be easily separated out from the rest of the global economy.

Applying a tax to revenues unconnected to economic value creation in a permanent establishment contravenes prevailing international tax principles. Back to top

What are alternatives to a DST?

There are different approaches to account for the digitalization of the economy in domestic and international tax rules. For example, India included digital products and services in its consumption tax, and Israel adopted a definition of “significant digital presence.” Back to top

Why has the U.S. responded with tariffs to digital services taxes in Europe?

In July 2019, France approved its digital services tax. Because the tax was expected to mainly impact U.S. companies, the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) opened a Section 301 investigation into whether the tax was discriminatory against U.S. businesses. The investigation report was released in December 2019, finding the digital services tax discriminatory.

Based on this finding, the Trump administration proposed retaliatory tariffs. However, the U.S. and France came to an agreement that the French digital services tax would not be collected until next year (although tax liability would accrue in 2020) and that the countries would continue the work on the taxation of the digital economy at the OECD level. Thus, the tariffs have not gone into effect.

The administration has also threatened tariffs against other countries that have been working to adopt digital services taxes. Back to top

How do digital services taxes relate to the OECD’s work on the taxation of the digital economy?

The OECD is currently hosting negotiations with over 130 countries that aim to adapt the international tax system. One goal is to address the tax challenges of the digitalization of the economy. For that, the OECD’s current proposal is that multinational businesses would pay some of their corporate income taxes where their consumers or users are located—a departure from current international tax principles.

However, despite these ongoing multilateral negotiations, several countries have decided to move ahead with unilateral measures to tax the digital economy. These unilateral measures have largely taken the form of digital services taxes. Back to top

Would an agreement on the taxation of the digital economy at the OECD level, if approved, take precedence over an individual country’s digital services tax (i.e., France)?

Generally, countries that have unilaterally implemented a DST have stated that the tax would be repealed when an international agreement is reached at the OECD level. However, there is some doubt, as, for example, the French DST law does not include a sunset clause. Back to top

What is the OECD BEPS project and what is its main objective?

The initial Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project officially began in 2013 with the publication of the OECD’s Action Plan on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting. The plan laid out a multilateral process for the OECD to review and address policies that allow multinational businesses to use tax planning practices to pay very low or no tax on income.

The BEPS project motivated the adoption of several anti-tax avoidance measures, such as controlled foreign corporation (CFC) rules, patent box nexus rules, thin-capitalization rules, transfer pricing regulations, and cross-country reporting requirements. Many countries have adopted these policies only recently, and their impact is becoming clearer as more evidence is evaluated.

However, one piece of unfinished business with the OECD project is the taxation of the digital economy. As a result, the OECD released a new work program on addressing the tax challenges of digitalization in May 2019. Since then, the OECD has been hosting public consultations and negotiations with more than 130 countries. In the process, the scope of the project has expanded, now also referred to as “BEPS 2.0.” It now consists of i) addressing the tax challenges of the digitalization of the economy (Pillar 1), and ii) addressing tax avoidance through a global minimum tax (Pillar 2). Back to top

What is the main objective of OECD Pillar 1?

Pillar 1, the proposal for a “Unified Approach,” aims to require businesses to pay more taxes where their consumers, and thus sales, are located. Under current international tax rules, multinationals’ corporate income tax liability is usually assessed where production is located rather than where sales occur. The OECD’s current proposal would mix the two. For highly profitable companies, some share of their profits would be taxed where sales occur, with the rest being taxed where production takes place.

A summary and analysis of Pillar 1 can be found here. Back to top

What is the main objective of OECD Pillar 2?

Pillar 2, the Global Anti-Base Erosion Proposal (“GloBE”), outlines a global minimum tax to further limit the incentives for businesses to locate profits in low-tax jurisdictions. The policy is inspired by new U.S. international tax rules that apply to foreign earnings of U.S. companies if those earnings are not subject to a minimum level of taxation abroad.

A summary and analysis of Pillar 2 can be found here. Back to top

Source: Tax Policy – FAQ on Digital Services Taxes and the OECD’s BEPS Project