Tax Policy – Insights into the Tax Systems of Scandinavian Countries

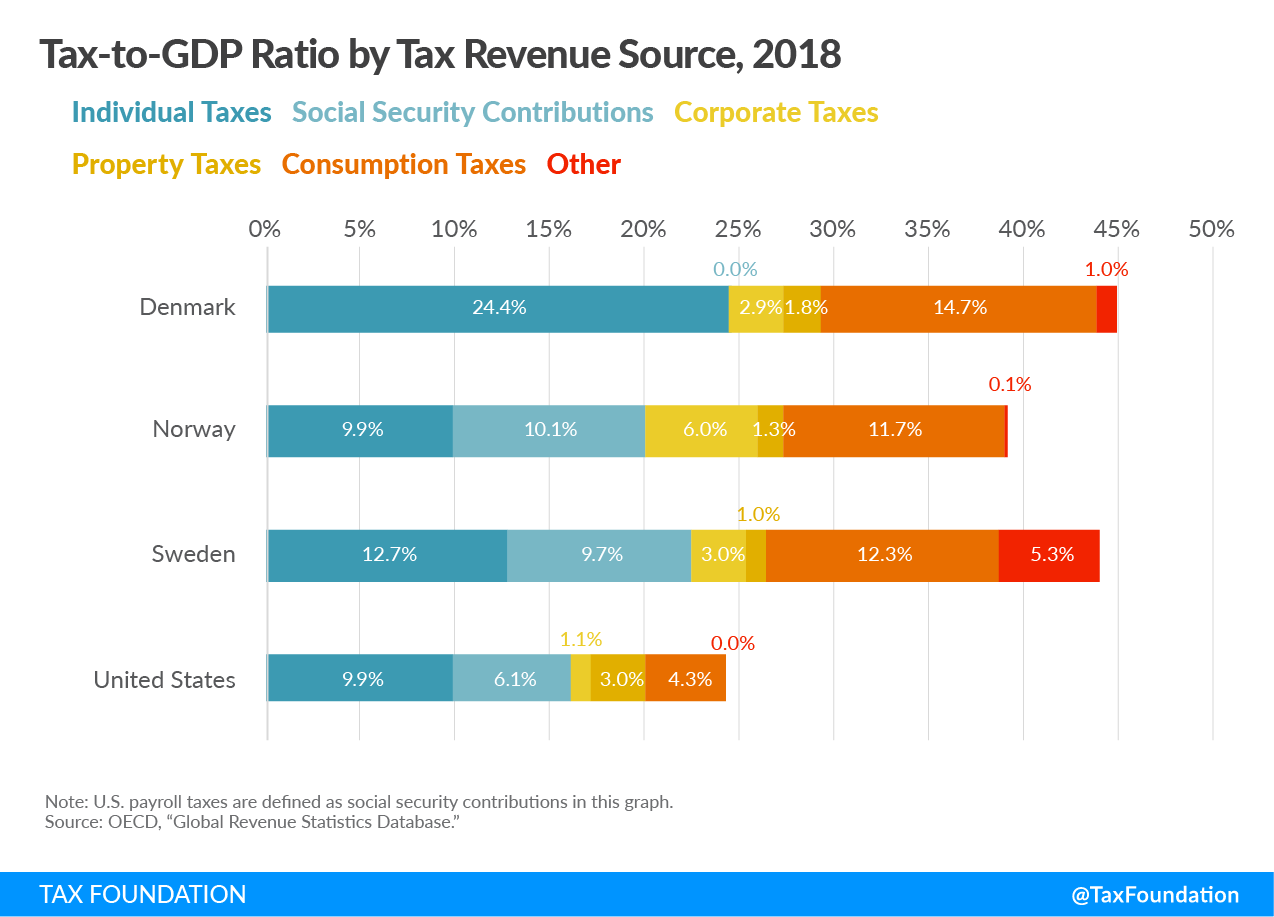

Scandinavian countries are well-known for their broad social safety net and their public funding of services such as universal healthcare, higher education, parental leave, and child and elderly care. High levels of public spending naturally require high levels of taxation. In 2018, Denmark’s tax-to-GDP ratio was at 44.9 percent, Norway’s at 39.0 percent, and Sweden’s at 43.9 percent. This compares to a ratio of 24.3 percent in the United States.

So how do Scandinavian countries raise their tax revenues? A first breakdown shows that consumption taxes and social security contributions[1]—both taxes with a very broad base—raise much of the additional revenue needed to fund their large-scale public programs.

Taxation of Labor Income

In 2018, Denmark (24.5 percent), Norway (20.0 percent), and Sweden (22.4 percent) all raised a high amount of tax revenue as a percent of GDP from individual taxes, almost exclusively through personal income taxes and social security contributions. This compares to 16.0 percent of GDP in individual taxes in the United States.

Tax Wedge

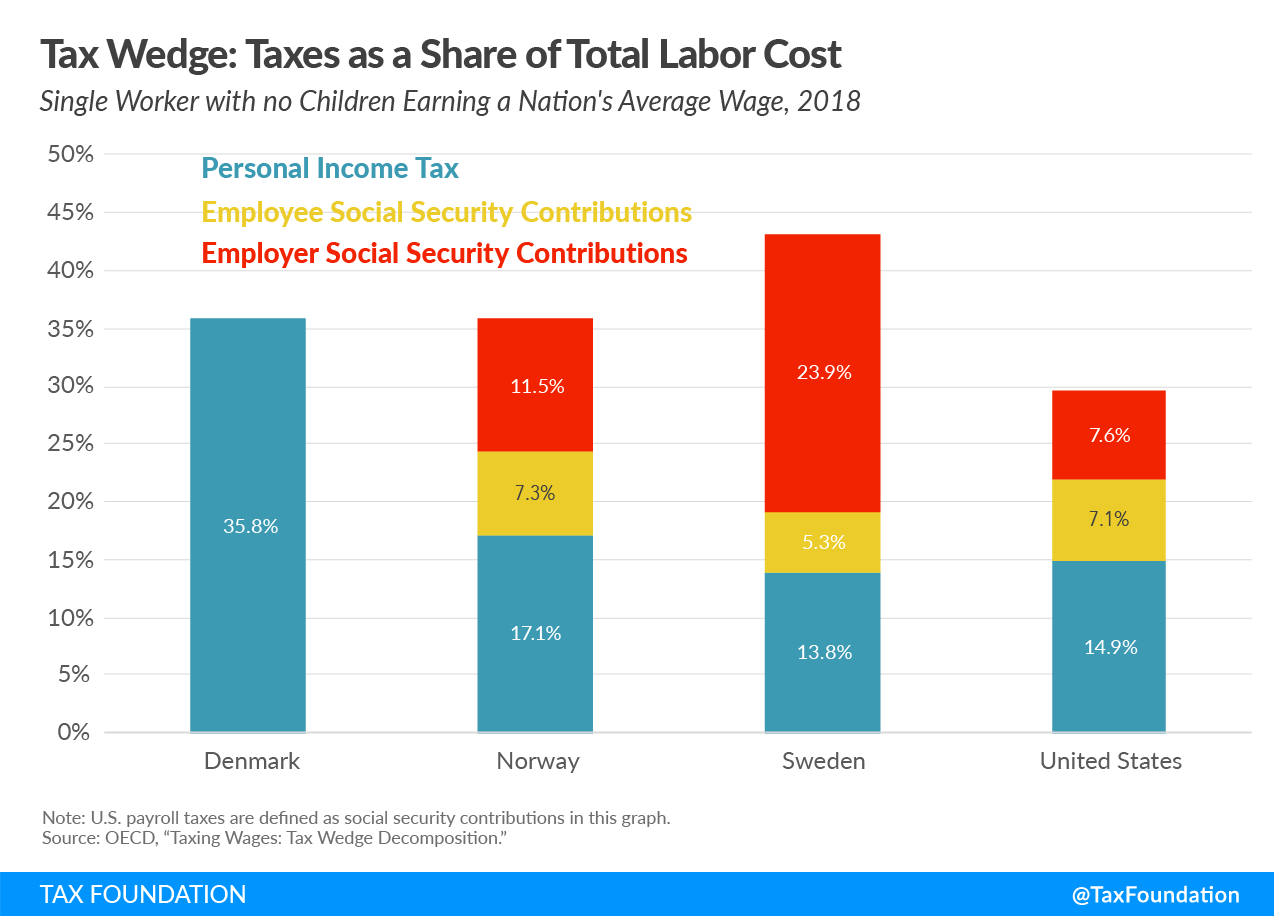

One way to analyze the level of taxation on wage income is to look at the so-called “tax wedge,” which shows the difference between an employer’s cost of an employee and the employee’s net disposable income.

In 2018, the tax wedge for a single worker with no children earning a nation’s average wage was 35.8 percent in Denmark, 35.9 percent in Norway, and 43.0 percent in Sweden. Although Denmark and Norway are below the OECD average of 36.1 percent, their tax wedges—and Sweden’s—are higher than the U.S. tax wedge of 29.6 percent.

Social Security Contributions

Social security contributions are levied on wages to fund specific programs and confer an entitlement to receive a (contingent) future social benefit. Social security contributions are largely flat taxes and tend to be capped.

Both Norway and Sweden levy high social security contributions, raising revenue of about 10 percent of GDP. In the United States, social security contributions (payroll taxes) raise revenue of approximately 6 percent of GDP.

In Norway and Sweden social security contributions—employer and employee side combined—account for 18.8 percent and 29.2 percent of total labor costs of a single worker with no children earning an average wage, respectively. This compares to 14.7 percent in the U.S.

Only Denmark does not impose social security contributions to fund its social programs. Instead, it uses a share of its individual income tax revenue for these programs.

Top Personal Income Taxes

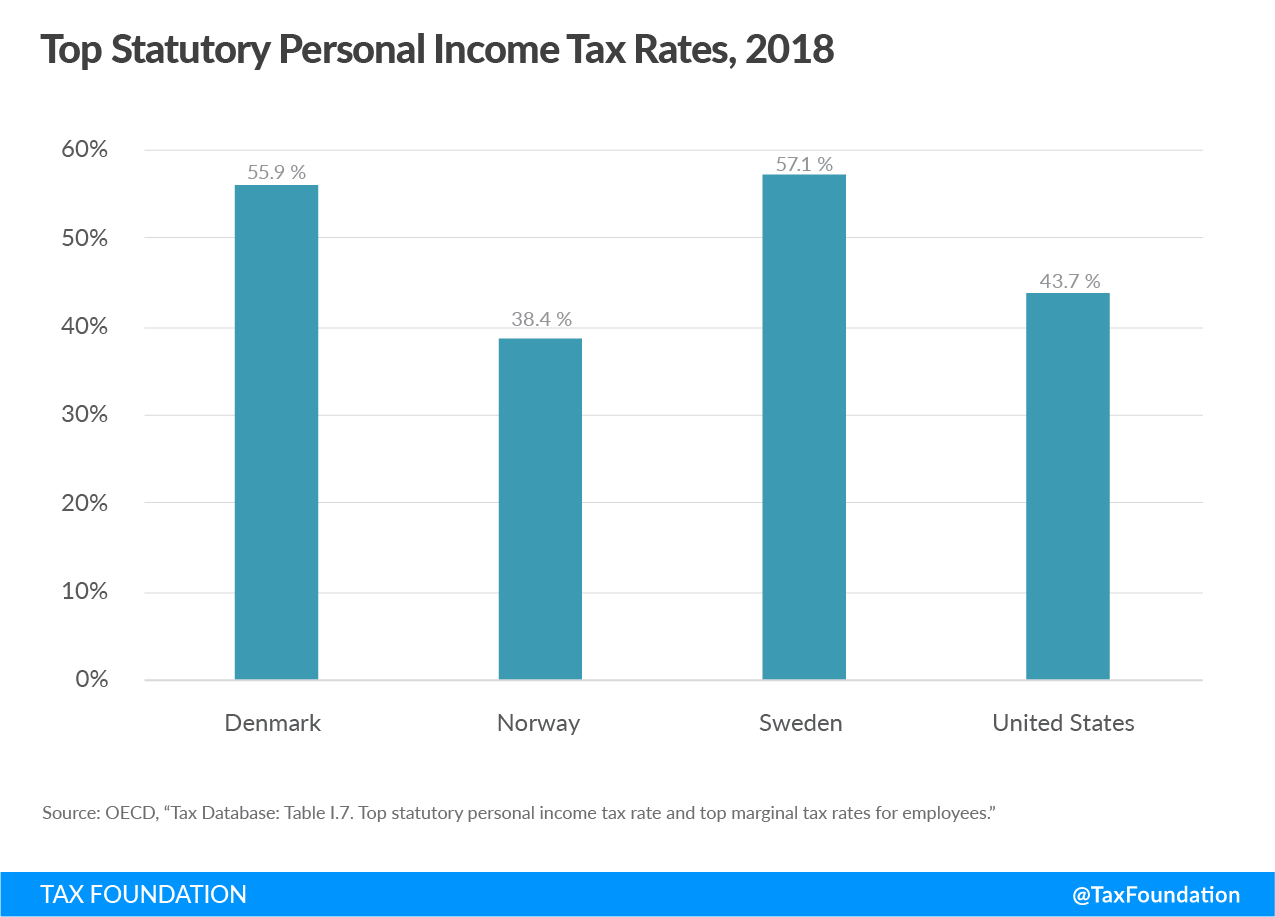

Top personal income tax rates are rather high in Scandinavian countries, except in Norway. Denmark’s top statutory personal income tax rate is 55.9 percent, Norway’s is 38.4 percent, and Sweden’s is 57.1 percent.

However, tax rates are not necessarily the most revealing feature of Scandinavian income tax systems. In fact, the United States’ top personal income tax rate is higher than Norway’s top rate.

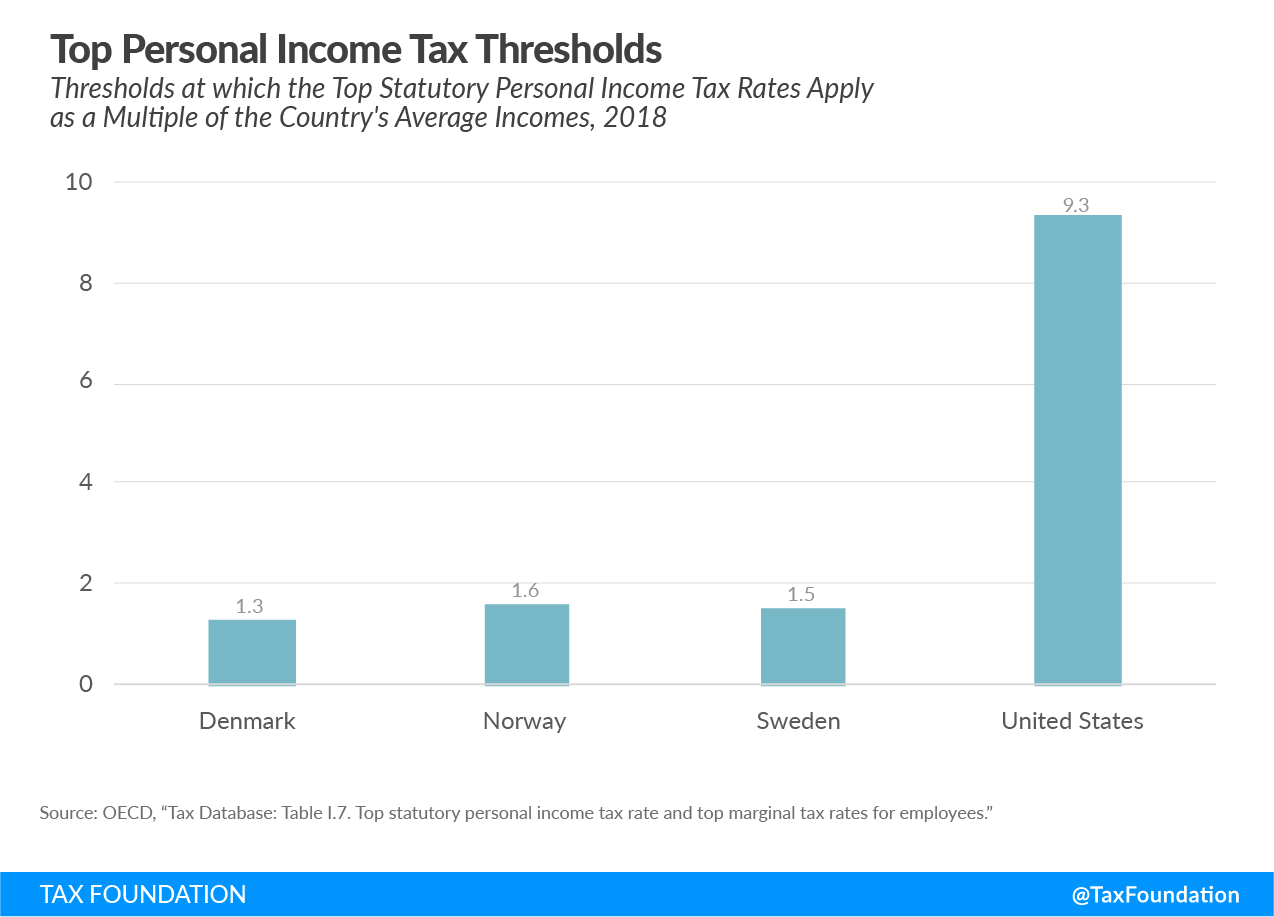

Scandinavian countries tend to levy top personal income tax rates on (upper) middle-class earners, not just high-income taxpayers. For example, in Denmark the top statutory personal income tax rate of 55.9 percent applies to all income over 1.3 times the average income. From the American perspective, this means that all income over $65,000 (1.3 times the average U.S. income of about $50,000) would be taxed at 55.9 percent.

Norway and Sweden have similarly flat income tax systems. Norway’s top personal tax rate of 38.4 percent applies to all income over 1.6 times the average Norwegian income. Sweden’s top personal tax rate of 57.1 percent applies to all income over 1.5 times the average national income.

In comparison, the United States levies its top personal income tax rate of 43.7 percent (federal and state combined) at 9.3 times the average U.S. income (around $500,000). Thus, a comparatively smaller share of taxpayers faces the top rate.

Importantly, the overall progressivity of an income tax depends on the structure of all tax brackets, exemptions, and deductions, not only on the top rate and its threshold.

Value-Added Taxes (VAT)

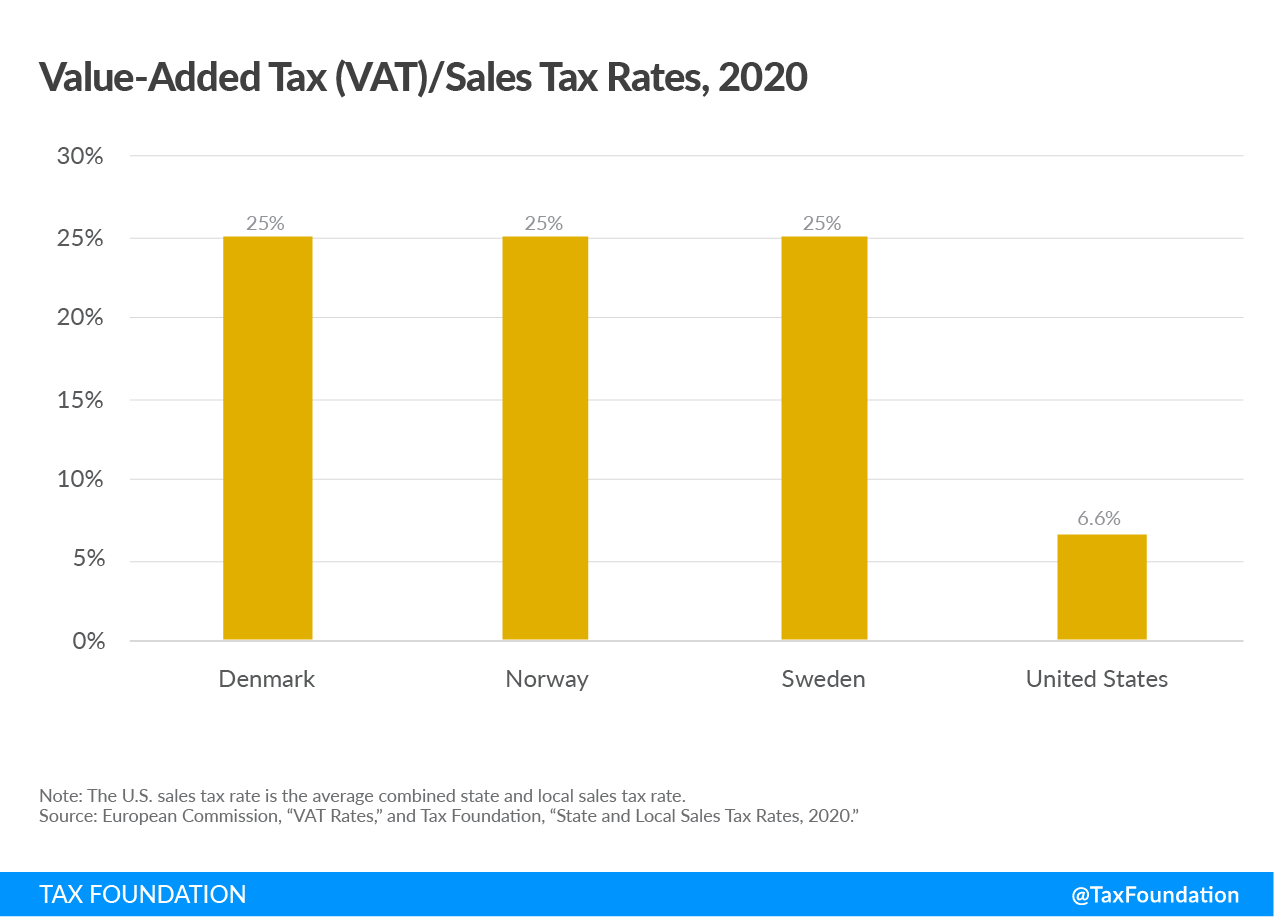

In addition to income taxes and social security contributions, all Scandinavian countries collect a significant amount of revenue from Value-Added Taxes (VATs). VATs are equivalent to sales taxes but levied on businesses throughout the production process.

As a tax on consumption, VATs are economically efficient: they can raise significant revenue with relatively less harm to the economy. However, depending on the structure, a VAT can be a regressive tax because it falls more on those that consume a larger share of their income, which tend to be lower-income earners.

In 2018, Denmark collected about 9.7 percent of GDP through the VAT, Norway collected about 8.5 percent, and Sweden collected about 9.3 percent of GDP. All three countries have VAT rates of 25 percent. The United States does not have a national sales tax or VAT. Instead, states levy sales taxes. The average tax rate across the country is about 6.6 percent. Due to the much lower rate, combined with a narrower base, U.S. sales taxes collect only about 2 percent of GDP in revenue.

Business and Capital Taxes

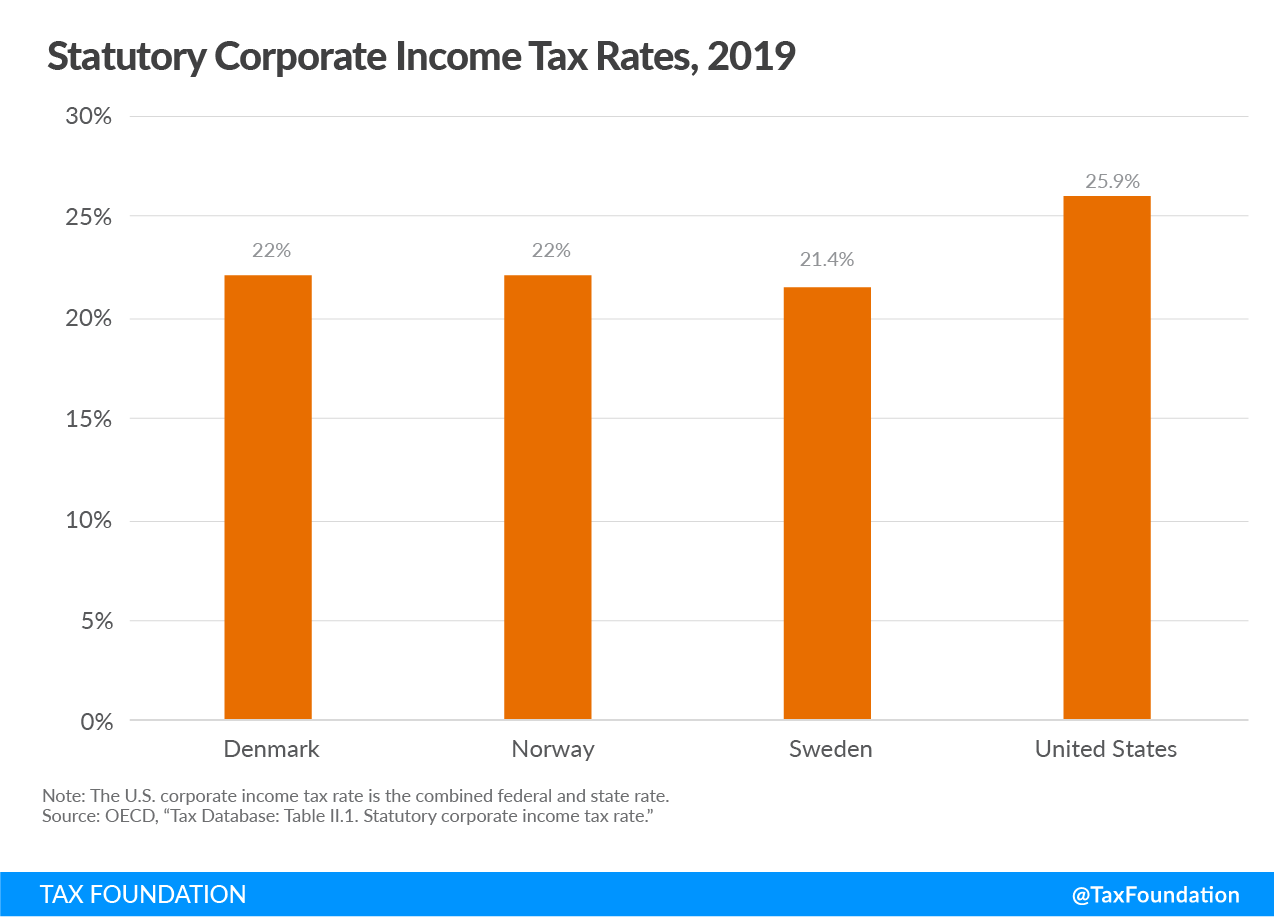

While Scandinavian countries raise a lot of revenue from individuals through the income tax, social security contributions, and the VAT, corporate income taxes—as in the United States—play a less significant role in terms of revenue. All Scandinavian countries’ corporate income tax rates are lower than the United States’ rate.

In 2018, the United States raised 1.1 percent of GDP from the corporate income tax, below the OECD average of 3.0 percent. Denmark and Sweden raised a share similar to the OECD average, at 2.9 percent and 3.0 percent of GDP, respectively. Norway is the exception with corporate revenue equal to 6.0 percent of GDP. Norway is situated on large reserves of oil and charges companies a corporate income tax rate of 78 percent on extractive activities.

Both Denmark’s and Norway’s statutory corporate income tax rates are 22 percent and Sweden’s corporate income tax rate is 21.4 percent. The U.S. tax rate on corporations is higher at 25.9 percent (federal and state combined).

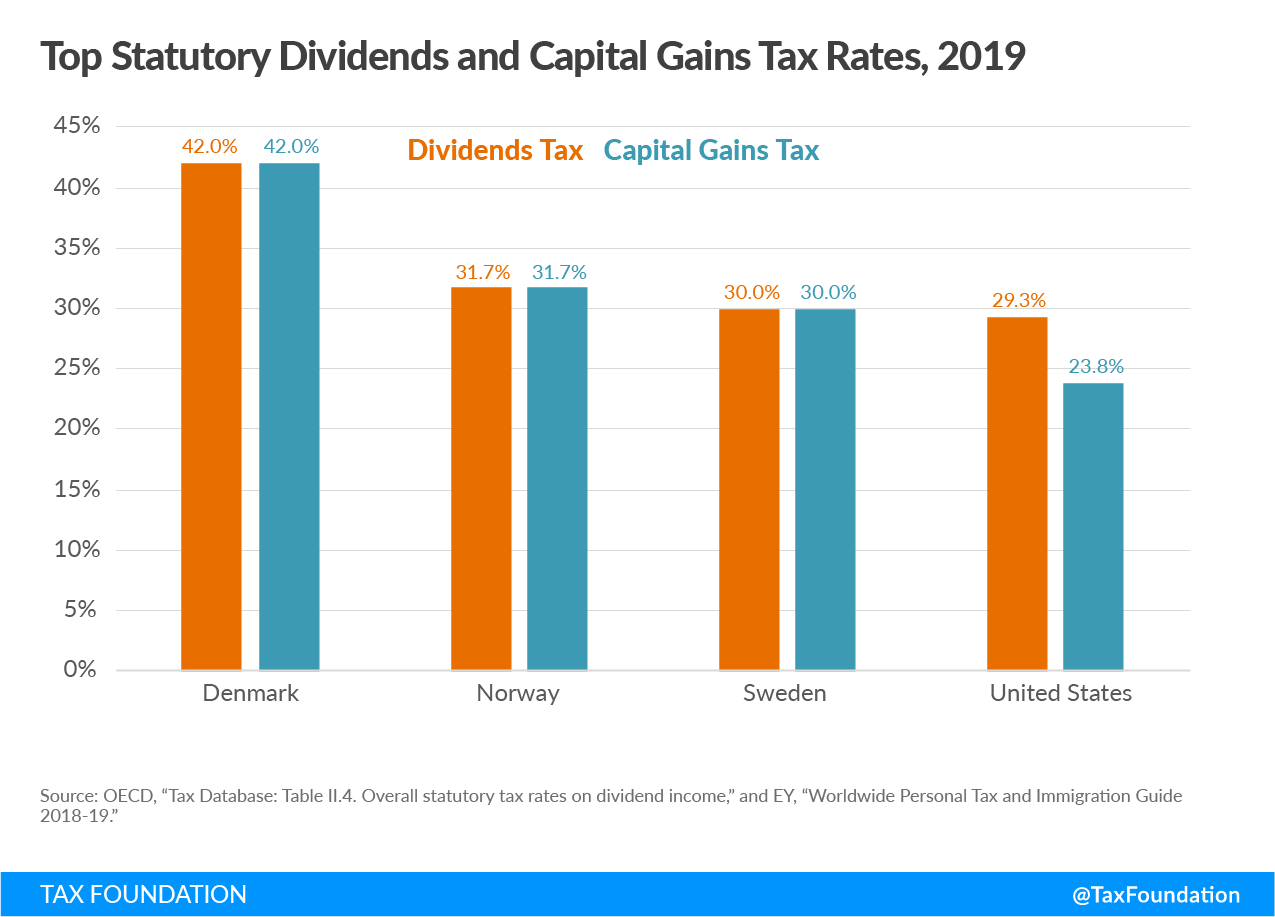

The taxation of capital income (capital gains and dividends) in Scandinavian countries is similar to the United States, with the exception of Denmark. Denmark’s top tax rate on dividends and capital gains is close to the highest in the OECD at 42 percent.

Norway’s (31.7 percent) and Sweden’s (30 percent) capital gains taxes and dividends taxes are more in line with the United States. The United States taxes dividends and capital gains at 29.3 percent and 23.8 percent, respectively.

Conclusion

Scandinavian countries provide a broader scope of public services—such as universal healthcare and higher education—than the United States. However, such programs necessitate higher levels of taxation, which is reflected in Scandinavia’s relatively high tax-to-GDP ratios.

Adopting such public services in the United States would naturally require higher levels of taxation. If the U.S. were to raise taxes in a way that mirrors Scandinavian countries, taxes—especially on the middle class—would increase through a new VAT and higher social security contributions and personal income taxes. Business and capital taxes would not necessarily need to be increased if policymakers were following the Scandinavian model. In fact, the corporate income tax rate would decline.

It does not come as a surprise that taxes in Scandinavian countries are structured this way. In order to raise a significant amount of revenue, the tax base needs to be broad. This means higher taxes on consumption through the VAT and higher taxes on middle-income taxpayers through higher social security contributions. Business taxes are a less reliable source of revenue (unless your country is situated on top of oil). In short, Scandinavian countries do not place above-average tax burdens on capital income and focus taxation on labor and consumption.

[1] In the U.S., social security contributions are generally called “payroll taxes”. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines social security contributions as compulsory payments that confer an entitlement to receive a (contingent) future social benefit. As this is largely the case with U.S. payroll taxes, the OECD considers U.S. payroll taxes as social security contributions. In this blog, they’ll also be referred to as social security contributions.

Source: Tax Policy – Insights into the Tax Systems of Scandinavian Countries