Tax Policy – Gas Tax Revenue to Decline as Traffic Drops 38 Percent

The coronavirus pandemic is affecting most aspects of the economy, and motor fuel consumption is no exception. As social distancing recommendations, shelter-in-place-orders, and quarantines have upended American life in an effort to slow the spread of the virus, road traffic has declined dramatically around the country.

While the mitigation policies will be felt across most tax categories including excise taxes, income taxes, and sales taxes, a key consequence of millions of people staying at home is fewer cars on the roads. Fewer people driving means fewer people buying gasoline, which may have positive effects on air pollution but could be detrimental to motor fuel excise tax revenue for federal and state governments.

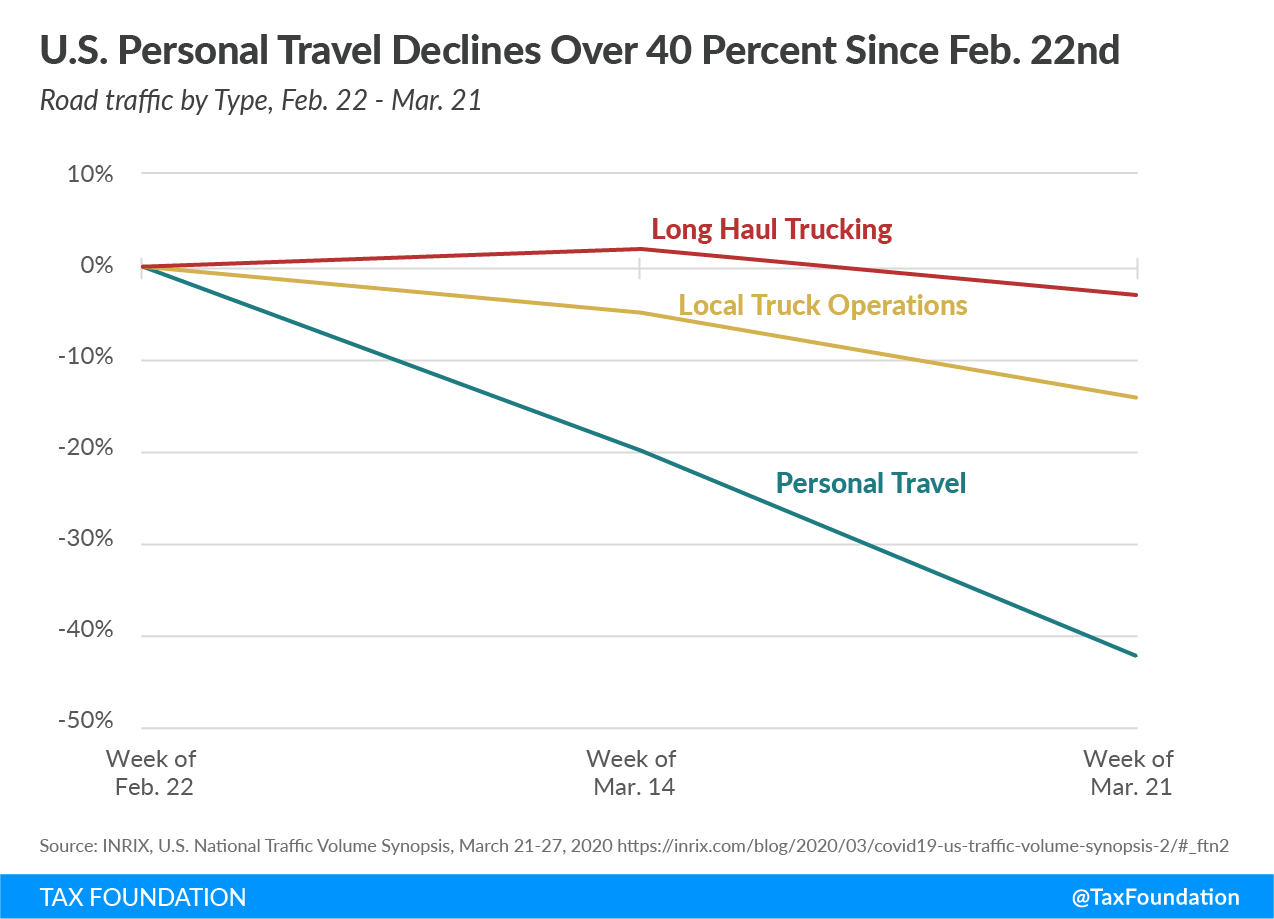

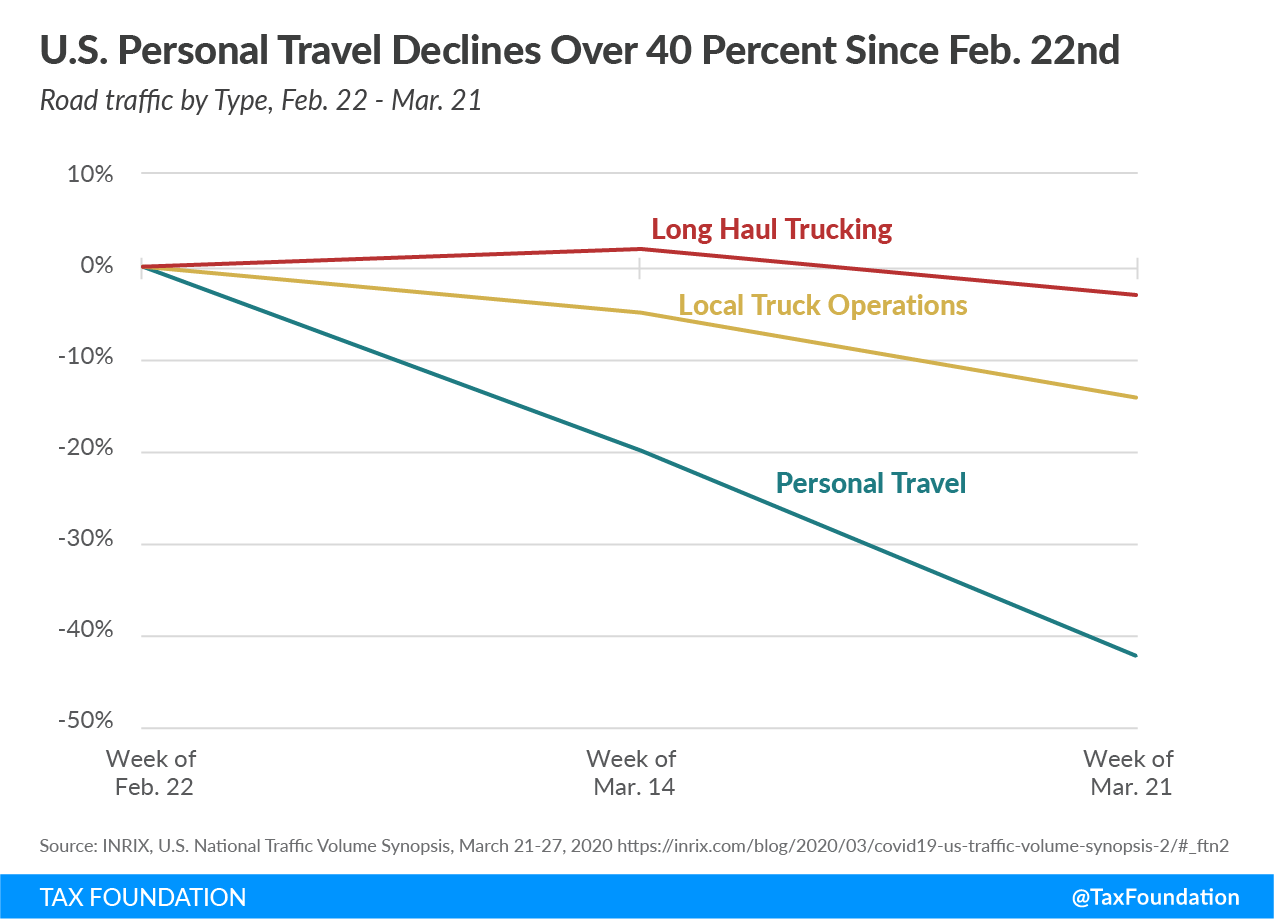

According to INRIX, a traffic data analytics company, compared to the week of February 22, just before the pandemic was officially called, personal travel nationwide for the week of March 23 had decreased by 44 percent. Even compared to the week before the March 23 week, there had been a 20 percent decrease. Trucking is also down, but not to the same degree, as businesses (especially retail stores and pharmacies) still need inventory. Long haul trucking is down 3 percent whereas local trucking operations are down 14 percent. The overall decline in road traffic is 38 percent. Such a decline will lead to a dramatic decline in gas tax revenue.

How much this will affect tax receipts is hard to estimate precisely because no one knows how long social distancing will be the norm. The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials has estimated a 30 percent drop in gas tax revenue based on data from the last recession (2008-2009). However, the current crisis’s mitigation policies make a one-to-one comparison challenging.

Toll collections are also likely to drop. With reductions in congestion, not only will traffic on all roads, including toll roads, decline, but the incentive to pay a premium for express-lane access disappears. In addition, toll road pricing is sometimes based on the level of traffic. Interstate 66 in Northern Virginia is an example of one such road. A comparison of the historical estimate of a rush hour 8.5-mile commute from Northern Virginia to Washington, D.C. shows a dramatic change in cost. In fact, the cost dropped from an average of $32 (week of Feb 22) to $1.75 on March 29. According to Fitch Ratings (a credit rating agency), nationwide receipts are down an average of 50-60 percent for toll systems.

In 2018 (the latest data), state governments raised $48.2 billion and the federal government raised $36 billion in motor fuel excise tax revenue. Revenue from these taxes is largely used to fund infrastructure maintenance and new projects. Declines in receipts will not affect all states similarly, as the amount of state and local road spending covered by gas taxes, tolls, user fees, and user taxes varies widely. It ranges from only 6.9 percent in Alaska to 71 percent in Hawaii. In the contiguous 48 states, North Carolina relies the most on dedicated transportation revenues (63.6 percent), while North Dakota relies on them the least (17.5 percent). States like Alaska and North Dakota keep their transportation taxes low in the same way that they keep all taxes on state residents low—by exporting taxes, primarily through the severance tax. Incidentally, these states should also see declines related to gasoline as the low price of crude oil will burn a hole in their budgets.

The federal government’s funding mechanism for the Highway Trust Fund, the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act, expires in September, and lawmakers must decide what to do about financing the fund going forward. If spending continues at current levels, with the current tax rate, the Congressional Research Service projects a $74.5 billion deficit over five years. The only options to relieve this deficit are to reduce spending or increase gas taxes (or a combination of both).

There may be room to increase the federal tax rate as it has not changed since 1993 and is not indexed to inflation. This has eroded the value of the tax over the last 27 years; to maintain constant value, an 18.4-cent per gallon tax in 1993 would have to be 26.1 cents today. In addition, increased fuel efficiency of newer cars has lowered the tax per mile for many drivers. Yet a tax increase on motor fuel may be ill-advised during a pandemic, because it is paramount that inventory for retail stores, pharmacies, and hospitals can move around the country.

Unlike the federal government, 31 states increased gas taxes in the last decade. Crucially, states tax gas mainly based on volume (per gallon), which is important as oil prices have dropped to their lowest price since 2002.

If the crisis brought on by the pandemic turns into a long-term recession, it could take years before gas tax revenue bounces back. During the last recession, receipts did not rebound to pre-crisis levels until 2011. (Extreme reductions are unlikely to persist, however, once stay-at-home orders are eliminated.) The effect of these developments should be considered by lawmakers when reviewing spending priorities for the remainder of the year as well as the next.

Source: Tax Policy – Gas Tax Revenue to Decline as Traffic Drops 38 Percent