Tax Policy – State Strategies for Closing FY 2020 with a Balanced Budget

Key Findings

- As states grapple with declining revenues and delay tax collections, policymakers must begin to think about how to close out their FY 2020 budgets consistent with balanced budget requirements.

- Every state but Vermont has a balanced budget requirement, but details vary across the country. In some states, a budget must be balanced when introduced, passed by the legislature, or signed by the governor, but need not be adjusted if it falls out of balance later. In many states, the budget must remain balanced.

- To address end-of-year shortfalls, states may consider spending cuts, drawing from reserves, accounting adjustments, and revenue enhancements. We offer a few suggestions and considerations for each option.

- Multiple strategies may prove appropriate to close out the current budget, but delaying expenditure reductions until the next budget may force harsher cuts later.

Introduction

The contrasting fiscal constraints of state and federal governments are on full display right now, as the federal government begins implementing a $2.2 trillion deficit-financed COVID-19 relief package while states must still find a way to balance their budgets as tax revenues decline and new needs arise. States must both close out the current fiscal year, in most cases without carrying over a negative ending balance, and budget for—or potentially revise an already-adopted budget for—fiscal year 2021 under tighter revenue constraints. In doing so, they have several tools at their disposal, but most can only buy time. Ultimately, states are constrained in a way the federal government is not: revenues and expenditures must be aligned, and the longer they are out of balance, the more intractable the problem becomes.

Sources of Revenue Shortfalls

The current crisis will affect almost every meaningful source of state revenue. The timing and intensity of these effects will, however, vary.

Historically, income taxes are more volatile than sales taxes and fall more sharply during a recession, but the COVID-19 pandemic is unique inasmuch as social distancing and shelter-in-place orders, along with mandatory closures of many nonessential businesses, have led to a sharp contraction of consumer spending. The goods and services seeing spikes in demand, moreover, like groceries and digital entertainment, are less likely to be subject to state sales tax.[1]

If the public health crisis extends for months, therefore, sales tax revenues may be the hardest hit. If, however, closure orders can be lifted more quickly, sales tax revenues should recover far more quickly than income tax revenues, because (at least when people can leave their homes) even in periods of economic contraction, consumption patterns do not decline commensurate with income. And whereas those newly unemployed will no longer have any taxable income, they will still make taxable purchases.

Individual income tax receipts decline not only because layoffs and reduced wages result in less taxable income, but because many taxpayers will claim substantial capital losses. Corporate income taxes tend to decline even more steeply during a recession, and take longer to recover, since corporate income taxes are imposed on net income and many businesses lose money during a downturn and accrue losses that can carry forward even after the recovery begins.

Excise tax revenues will be adversely affected as well and may be eliminated entirely in some cases. Telework and other reductions in travel mean motor fuel taxes will plummet, as will special excise taxes on tourism and hospitality. Closures of casinos, bars, and other establishments responsible for considerable “sin tax” revenue will also impact states’ bottom lines.[2]

Even timing issues will come into play, particularly as states permit tax filing and payment delays as a means of financial assistance and a way to help taxpayers avoid visiting tax preparers’ offices or needing to track down receipts and documents during a pandemic. Income taxes are typically withheld throughout the year, or paid quarterly, limiting the impact of delayed filing and payment. But postponing an income tax payment date from April 15 to July 15, or delaying requirements for remitting sales or other taxes, can still be significant, pushing some collections into the next fiscal year just while states are trying to close out the current one.

Meanwhile, the coronavirus crisis will dramatically expend the use of public benefits and social insurance programs, from unemployment benefits to SNAP benefits and other assistance funded, wholly or in part, by states. The Great Recession, which ran from December 2007 through June 2009, is the most analogous situation available to draw upon, but early indications of initial unemployment benefit claims, and the potential for a lengthy societal dislocation, could quickly make the comparison inadequate.

Balanced Budget Requirements in Brief

Perhaps surprisingly, there is not a consensus answer to the question of how many states have a balanced budget requirement, since the details of each state’s requirements vary. It is generally held that every state but Vermont has some sort of balanced budget requirement on the books, and that Vermont maintains a balanced budget even in the absence of a legal obligation to do so. A few states only have statutory requirements, which could theoretically be waived by the legislature, and some constitutional requirements functionally only constitute a limitation on debt.

In practice, however, states are bound not only by constitution, statute, and tradition, but by practical considerations as well: states cannot print money, and operate under constraints in issuing bonds, so they must largely live within their means.

One variation in how states implement balanced budget requirements is suddenly important, however: whether the requirement binds the governor when she introduces a budget, the legislature when it passes one (enrollment), the governor when she signs it, the state when it executes it, or some combination of the above.[3] If, for instance, a state enacted a FY 2020 budget that was balanced at the time of its adoption in the spring of 2019, it is likely facing a deficit now as revenue collections sputter. In most states, some sort of action would be required to bring the budget into balance before the fiscal year ends (typically June 30), but some states permit the fiscal year to end with a negative balance, carrying over a deficit to the next fiscal year.

| State | Introduced | Enrolled | Signed | Executed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Alaska | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Arizona | ✓ | |||

| Arkansas | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| California | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Colorado | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Connecticut | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Delaware | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Florida | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Georgia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Hawaii | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Idaho | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Illinois | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Indiana | ✓ | |||

| Iowa | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Kansas | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Kentucky | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Louisiana | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Maine | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Maryland | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Massachusetts | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Michigan | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Minnesota | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Mississippi | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Missouri | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Montana | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Nebraska | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Nevada | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| New Hampshire | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| New Jersey | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| New Mexico | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| New York | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| North Carolina | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| North Dakota | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ohio | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Oklahoma | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Oregon | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Pennsylvania | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Rhode Island | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| South Carolina | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| South Dakota | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Tennessee | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Texas | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Utah | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Vermont | ||||

| Virginia | ✓ | |||

| Washington | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| West Virginia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Wisconsin | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Wyoming | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| District of Columbia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Note: Arizona does not technically operate under a balanced budget requirement but has extremely limited capacity to take on debt, which we represent here as an obligation to execute a balanced budget. | ||||

| Sources: National Association of State Budget Officers; Tax Foundation research. | ||||

Even in states which allow an operating deficit to carry over to the next fiscal year, but especially in others, states will have to employ several strategies to close out the current fiscal year in a way that is both prudent and consistent with state law. None of the choices will be pleasant, and some will only buy time, but states are now working against the clock.

Options for Closing a FY 2020 Budget Gap

With only three months remaining in most states’ fiscal 2020 budgets, options for closing any substantial shortfall are somewhat constrained. In the longer term, the only responsible way to balance budgets is to equalize revenues and expenditures—and as the crisis lengthens, states will undoubtedly have to adjust their spending priorities, just as they did during the Great Recession and other recessions before it. Efforts to close the current budget gaps, however, will likely pair revenue cuts with other adjustments, some more sound than others.

Reducing Expenditures

Given the severity and likely length of the present crisis, states must carefully examine their current expenditures. States’ FY 2020 general fund expenditures were 4.8 percent higher than FY 2019 budgets, representing about $42.1 billion in higher spending.[4] State general fund revenues are now 18.6 percent higher than their pre-Great Recession peak in real (inflation-adjusted) terms and 34.0 percent above the worst four quarters of the Great Recession.[5]

States were forced to trim budgets during the Great Recession and will be required to do so again. Beginning to reduce spending slated for the final months of FY 2020, a fiscal year that began one day before the U.S.’s streak of economic expansion became the longest period of economic growth in U.S. history,[6] can help ease the pain later, forestalling deeper cuts in FY 2021.

Drawing from Reserves

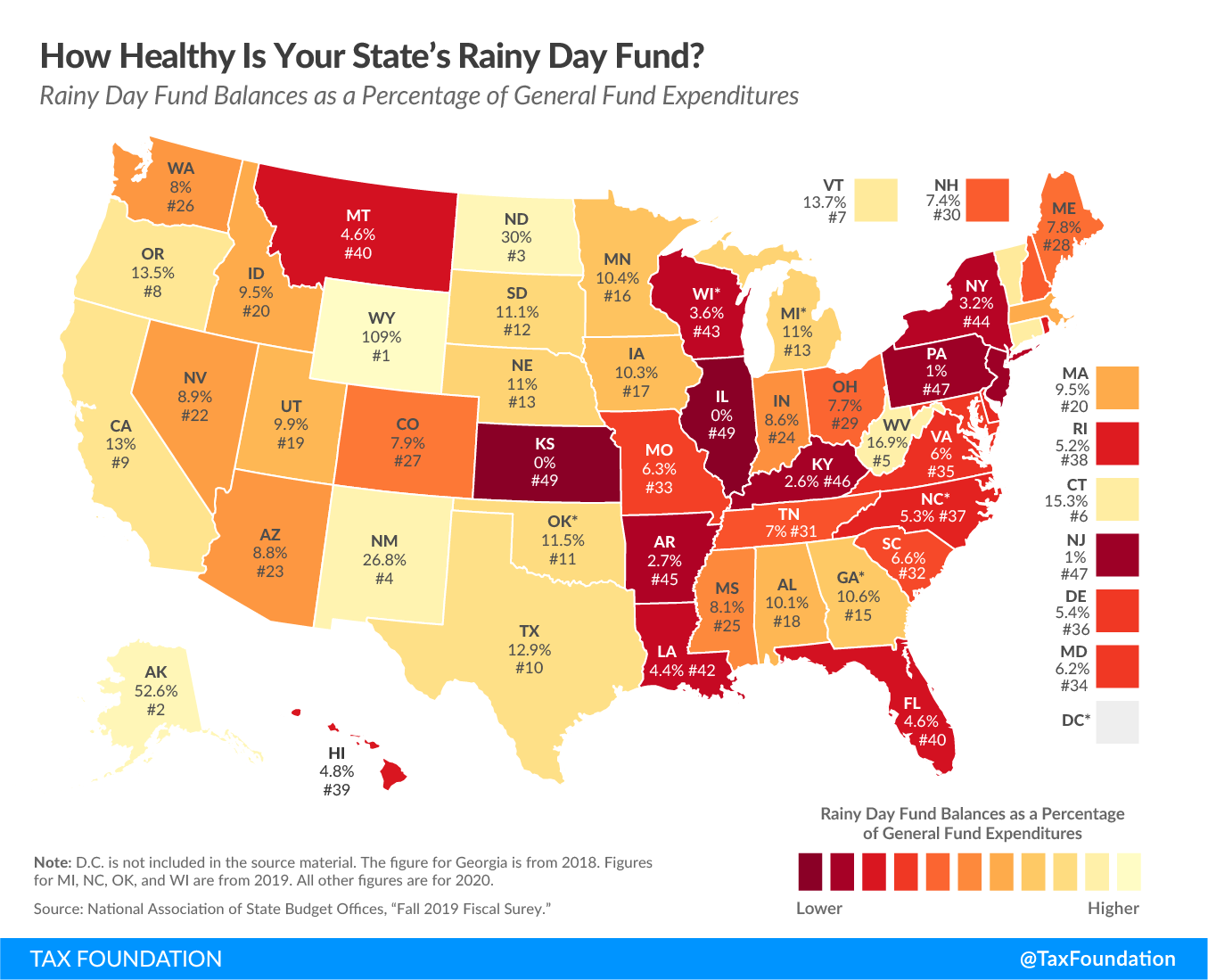

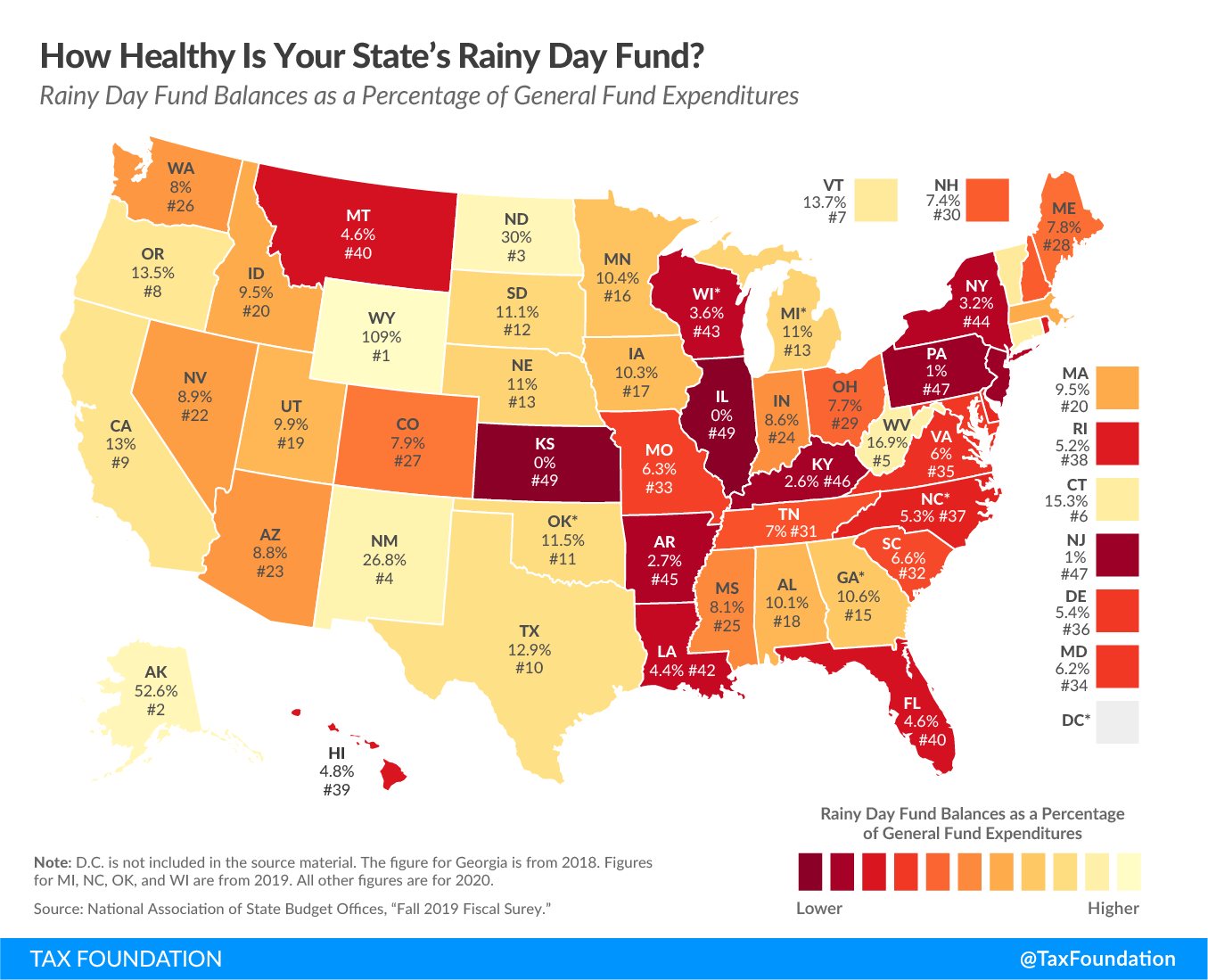

Second, states can access reserve funds and dedicated accounts to provide a one-time revenue infusion, though they should be cognizant that greater needs could arise in the next fiscal year, which cautions against draining these accounts too quickly. Some states carry unappropriated general fund balances. All now have revenue stabilization funds, popularly known as rainy day funds. And all have a range of dedicated accounts, some constitutionally or otherwise protected but others readily accessible, that can be swept into the general fund to meet more urgent needs.

The use of unappropriated balances is by far the most straightforward; this revenue is available for the state to meet unexpected shortfalls or unanticipated spending obligations and may be used without constraint. The existence of such a surplus from which to draw should not be viewed as eliminating the need to reduce spending, because a lengthy crisis will exhaust state reserves quickly, with optional current spending cutting into the resources necessary to maintain funding for essential programs later. Still, these balances are by far the easiest way to patch an end-of-year revenue gap.

State rainy day funds are also available, though states should again take care in how much they draw down the funds, saving funds for FY 2021 where possible. The median rainy day fund’s balance was 8 percent of state general fund expenditures entering fiscal year 2020, far better than the 4.8 percent balance states posted at the beginning of fiscal year 2008, prior to the Great Recession.[7] Some states, however, have almost no cushion: Illinois and Kansas have almost completely empty reserve funds, and New Jersey and Pennsylvania both have funds valued at only 1 percent of their annual general fund expenditures.

| State | Amount ($ millions) | Percent of Expenditures |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | $945 | 10.1% |

| Alaska | $2,279 | 52.6% |

| Arizona | $1,019 | 8.8% |

| Arkansas | $153 | 2.7% |

| California | $19,204 | 13.0% |

| Colorado | $1,046 | 7.9% |

| Connecticut | $2,965 | 15.3% |

| Delaware | $252 | 5.4% |

| Florida | $1,574 | 4.6% |

| Georgia* | $2,557 | 10.6% |

| Hawaii | $396 | 4.8% |

| Idaho | $373 | 9.5% |

| Illinois | $4 | 0.0% |

| Indiana | $1,446 | 8.6% |

| Iowa | $784 | 10.3% |

| Kansas | $0 | 0.0% |

| Kentucky | $304 | 2.6% |

| Louisiana | $430 | 4.4% |

| Maine | $306 | 7.8% |

| Maryland | $1,198 | 6.2% |

| Massachusetts | $3,308 | 9.5% |

| Michigan* | $1,149 | 11.0% |

| Minnesota | $2,487 | 10.4% |

| Mississippi | $465 | 8.1% |

| Missouri | $654 | 6.3% |

| Montana | $118 | 4.6% |

| Nebraska | $510 | 11.0% |

| Nevada | $394 | 8.9% |

| New Hampshire | $115 | 7.4% |

| New Jersey | $401 | 1.0% |

| New Mexico | $2,015 | 26.8% |

| New York | $2,476 | 3.2% |

| North Carolina* | $1,254 | 5.3% |

| North Dakota | $727 | 30.0% |

| Ohio | $2,692 | 7.7% |

| Oklahoma* | $806 | 11.5% |

| Oregon | $1,487 | 13.5% |

| Pennsylvania | $340 | 1.0% |

| Rhode Island | $210 | 5.2% |

| South Carolina | $569 | 6.6% |

| South Dakota | $189 | 11.1% |

| Tennessee | $1,100 | 7.0% |

| Texas | $7,830 | 12.9% |

| Utah | $791 | 9.9% |

| Vermont | $226 | 13.7% |

| Virginia | $1,375 | 6.0% |

| Washington | $1,948 | 8.0% |

| West Virginia | $810 | 16.9% |

| Wisconsin* | $649 | 3.6% |

| Wyoming | $1,667 | 109.0% |

| District of Columbia | $1,430 | 14.4% |

| * These states did not report FY 2020 rainy day fund balances. Figures for Michigan, North Carolina, and Oklahoma are from FY 2019, and Georgia figures are from FY 2018. | ||

| Source: National Association of State Budget Officers. | ||

Revenue stabilization funds vary in their withdrawal conditions and mechanisms and are not as easily accessible as unappropriated reserves. However, they are an important part of states’ toolkits in an economic downturn and were intended for just such a time.

Finally, state treasuries tend to contain a smattering of dedicated funds holding money in reserve for specific expenditures. Sometimes these funds are constitutionally dedicated, financed by taxes or fees directly related to their intended purpose. Other times, however, money sits in these accounts almost forgotten, their intended uses no longer urgent, or at least less pressing than seeing the state through an economic contraction.

States should approach such reserves cautiously. Depleting funds being held against some unchanged future expense only creates a later crisis, and “sweeping” dedicated money generated by a user-pays tax or fee to some unrelated purpose can be a breach of trust, particularly if the fund is not replenished later. An economic downturn can, however, be a good time to identify “orphan” funds that no longer serve a legitimate purpose, or those dedicated for purposes that no longer constitute a state priority. These are one-time revenue enhancements, but can help states in the short term, including in addressing timing issues like some portion of income and sales tax collections being deferred to the next fiscal year.

Making Accounting Adjustments

Ideally, accounting adjustments should be avoided, as they are essentially gimmicks and only increase burdens—or complicate accounting—later. Occasionally, however, it is possible for states to book expenses to the next fiscal year, which can buy time if states are unable to adjust their budgets in late FY 2020 or if, due to tax payment delays, they anticipate receiving a sizable share of the revenue anticipated in FY 2020 in early FY 2021.

Sometimes states also try to shift revenues forward through accelerated payment schedules, but these can be difficult to unwind and impose substantial burdens on taxpayers. Some states, for instance, adopted accelerated sales tax payments during the Great Recession, requiring businesses to pay estimated sales taxes in advance, essentially giving the state one extra payment to help close budget gaps.

Not only does this require businesses to remit based on estimates of future sales, however, but they may have to do so in perpetuity, because the only way to unwind the acceleration is to forgo a payment in the future, something states have sometimes been loath to do even years after a recession. In the present crisis, moreover, with many retail establishments forced to close or limit their operations, accelerating the sales tax would yield little revenue and be at cross-purposes with state and federal efforts to assist these struggling businesses. Many states, in fact, have done the opposite, authorizing a delay in remitting sales tax owed in an effort to give businesses additional cash flow.

Finally, in some states, governments can simply carry over a negative balance into the next fiscal year, though such an approach cannot be sustained for long and can only buy time, not solve the larger problem.

Revenue Increases

Some states will inevitably seek new revenues to help address budget gaps, but the final few months of a fiscal year provide very little time to generate revenue from new or higher taxes, and such taxes would be at cross-purposes with the policies of financial relief and economic stimulus that all levels of government are currently implementing. Income tax increases, which would likely be for tax year 2021, could not raise revenue in time to plug holes in the FY 2020 budget; sales and most excise taxes are likely to perform poorly for the remainder of the fiscal year; and new or enhanced taxes on business activity are likely to be ineffective and counterproductive. Whatever role new revenues play in these deliberations, those are likely to be matters for later fiscal years, not the one ending June 30, 2020.

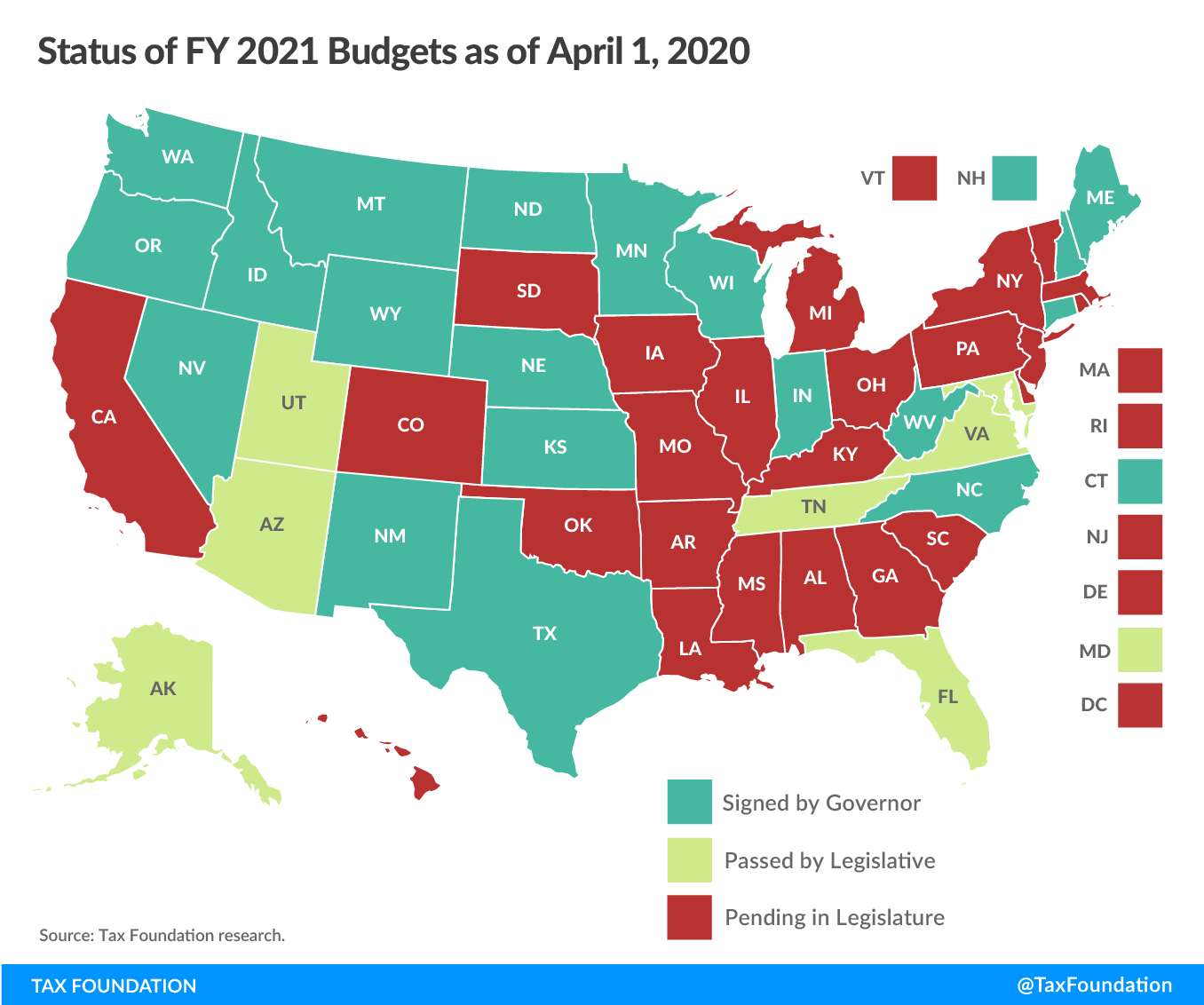

Considerations for FY 2021 Budgets

States that have already adopted a FY 2021 budget almost certainly did so under revenue assumptions that are no longer realistic given the pandemic-linked economic downturn. This is both a blessing and a curse. A blessing because, unlike many of their peers, they do not face the immediate need to find a way to balance the next fiscal year’s budget based on highly uncertain but sharply lower revenue projections. Their budgets were balanced when adopted, meeting most states’ legal obligations—at least for now. A curse, though, because delaying adjustments too long will only make the problem worse, forcing states to make sharper corrections later in the next fiscal year to bring the budget into balance.

| Signed by Governor | Enrolled by Legislature | Pending in Legislature |

|---|---|---|

| Connecticut | Alaska | Alabama |

| Idaho | Arizona | Arkansas |

| Indiana | Florida | California |

| Kansas | Maryland | Colorado |

| Maine | South Dakota | Delaware |

| Minnesota | Tennessee | Georgia |

| Montana | Utah | Hawaii |

| Nebraska | Virginia | Illinois |

| Nevada | Iowa | |

| New Hampshire | Kentucky | |

| New Mexico | Louisiana | |

| North Carolina | Massachusetts | |

| North Dakota | Michigan | |

| Oregon | Mississippi | |

| Texas | Missouri | |

| Washington | New Jersey | |

| West Virginia | New York | |

| Wisconsin | Ohio | |

| Wyoming | Oklahoma | |

| Pennsylvania | ||

| Rhode Island | ||

| South Carolina | ||

| Vermont | ||

| District of Columbia | ||

| Source: Tax Foundation research. | ||

States adopting budgets now may wish to prioritize expenditures, granting governors the authority (where they currently lack it, and where it is consistent with state constitutions) to reduce some spending throughout the year to adjust to uncertain revenues. If budgeting for the higher bound of revenue estimates, they may wish to adopt budgets which maintain cash reserves, as it is easier to bring spending back online if revenues recover or additional federal aid becomes available than it is to make cuts toward the end of the year.

New expenditures directly related to the COVID-19 epidemic, meanwhile, are eligible for federal reimbursement under the new Coronavirus Relief Fund, and other federal assistance can help offset expenditures states might otherwise be forced to undertake.[8]

Conclusion

State options for closing FY 2020 shortfalls are limited and may ultimately include drawing on reserve funds and even accounting tricks. To the extent possible, however, states should begin prioritizing spending now and reducing or postponing nonessential spending. No one knows how steep the decline in state revenues will be in the coming months, but the loss will be significant, and the longer states maintain a business-as-usual posture, the more difficult the ultimate adjustments will be.

[1] Jared Walczak, “Income Taxes are More Volatile Than Sales Taxes During an Economic Contraction,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 17, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/income-taxes-are-more-volatile-than-sales-taxes-during-recession/.

[2] Ulrik Boesen, “What Happens with State Excise Tax Revenue During a Pandemic?” Tax Foundation, Mar. 25, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/happens-state-excise-tax-revenues-pandemic/.

[3] National Association of State Budget Officers, “Budget Processes in the States,” Spring 2015, 51-55, https://www.nasbo.org/reports-data/budget-processes-in-the-states.

[4] Id., “Fiscal Survey of the States,” Fall 2019, https://www.nasbo.org/reports-data/fiscal-survey-of-states.

[5] U.S. Census Bureau, “Quarterly Summary of State & Local Tax Revenue (QTAX),” multiple years, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/qtax.html.

[6] The Economist, “America’s Economic Expansion is Now the Longest on Record,” July 2, 2019, https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2019/07/02/americas-economic-expansion-is-now-the-longest-on-record.

[7] National Association of State Budget Officers, “Budget Processes in the States,” 65.

[8] Jared Walczak, “State Aid Provisions of the Federal Coronavirus Response Bill,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 25, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/state-aid-coronavirus-provisions-of-the-federal-coronavirus-response-bill/.

Source: Tax Policy – State Strategies for Closing FY 2020 with a Balanced Budget