Tax Policy – Historic Oil Price Burns Hole in State Budgets

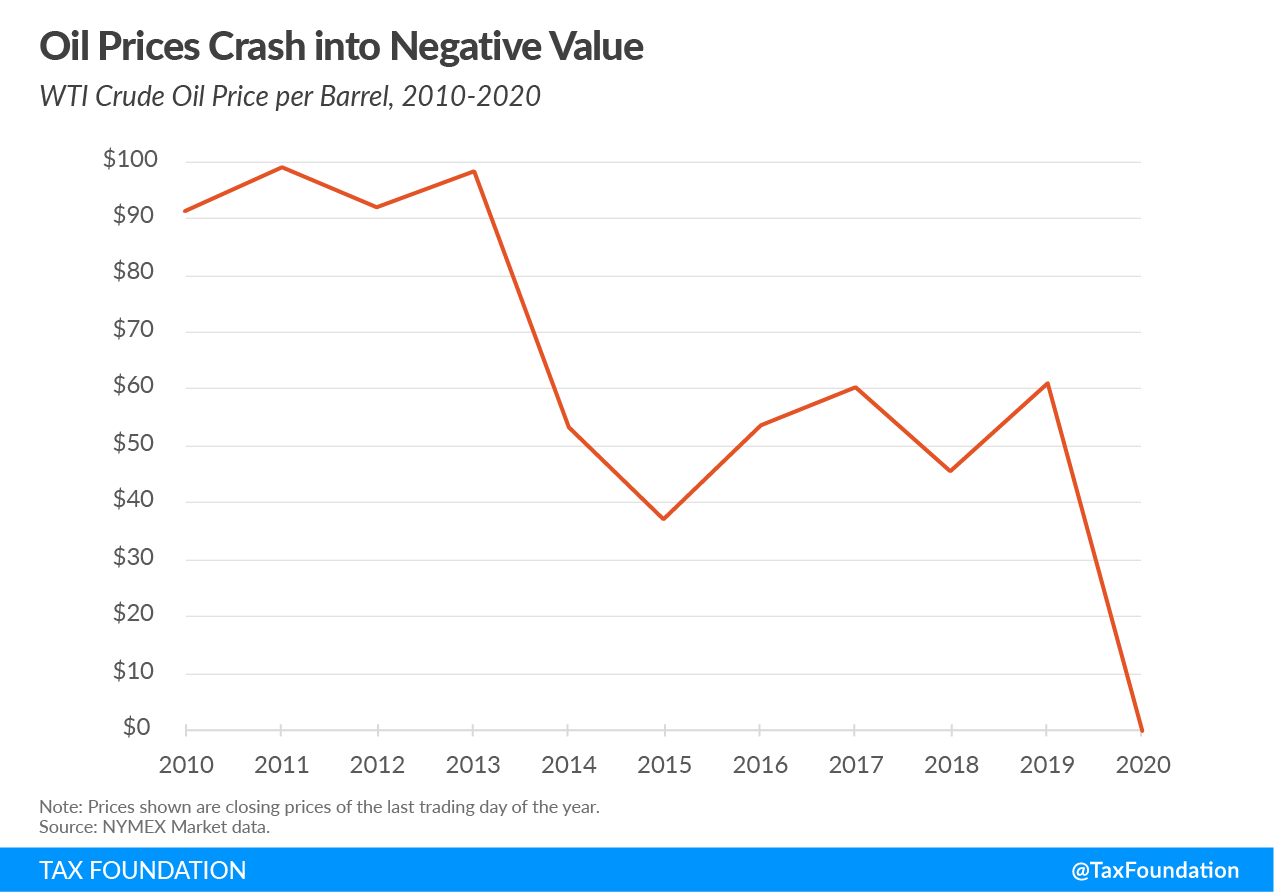

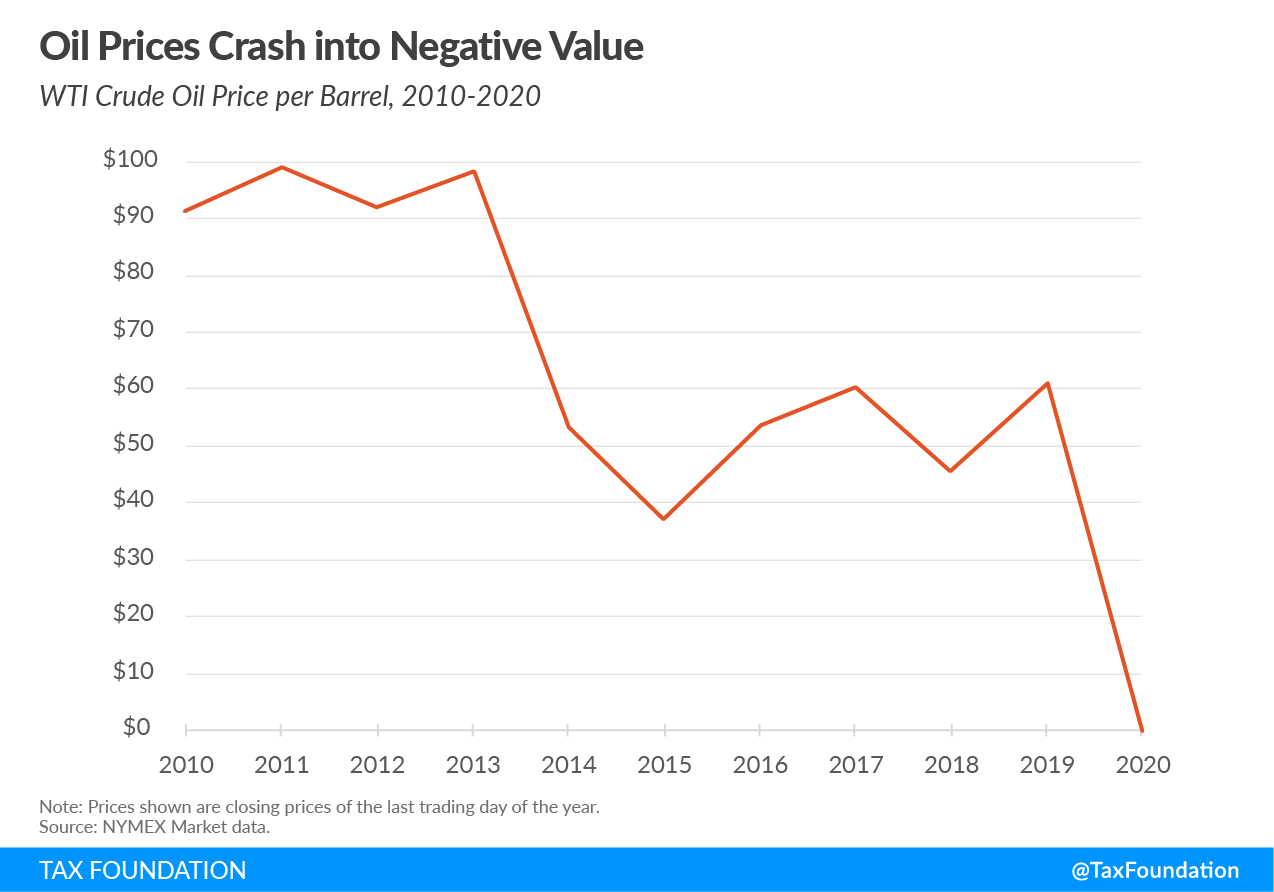

On April 20, the price for U.S. West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil for May contracts was trading at a historically low -$37 per barrel (WTI serves as a reference price for crude oil). To compare, in May 2019, WTI crude was selling at $71 a barrel.

In the last few days, WTI June contracts have gained some ground, but analysts warn that these gains may be short-lived. If a downward price trend continues, despite this momentary recovery, through the next few months, it will have a severe impact on the several states that collect significant parts of their state revenue from oil severance taxes. The combination of low oil prices and the economic crisis spurred by the coronavirus outbreak means these states have ample reason to worry about their finances.

Two states, Alaska and North Dakota, collect revenue primarily from oil-related taxes. Alaska collects 50 percent of its revenue from severance taxes and a total of 81 percent of its revenue from taxes levied on the oil industry. North Dakota collects 53 percent of its revenue from severance taxes. Wyoming (22 percent) and New Mexico (20 percent) also generate a significant portion of state tax revenue from severance taxes on oil extraction, in addition to other taxes paid by the oil industry.

While direct taxes on extraction and production is the most obvious source of state revenue derived from oil, states also collect it from corporate and personal income taxes, property taxes, and royalties. Further, oil production businesses may support other jobs in the local communities where they operate.

This post focuses on the two states most exposed to the price decline, but other states with meaningful revenue from the oil industry may experience fiscal difficulties as well.

Negative price on WTI crude oil is a historic first but has happened because the cost of extracting, delivering, and storing the oil outweighs the profit from selling it. The decline has been driven by a combination of a price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia as well as a lack of demand due to the coronavirus pandemic. Globally, demand is down 30 percent.

The demand is key because some oil futures contracts are settled physically, which means that the owner of any contract will receive the physical oil. This fact added urgency to the market as May contracts, which traded at a negative value, expired on April 21. May contracts have to be settled in the delivery month (May) in Cushing, Oklahoma, where contract owners must take possession of the oil. However, refinery capacity across the country is down because demand is down, which means oil is simply sitting in storage in Cushing with no capacity to book any more local storage. Further, oil wells cannot easily be stopped without damaging the well, so production continues even when there is no demand.

Importantly, June contracts are still trading positive, which supports the notion that it is the cost of refining and storage driving the price down on the May contracts. Nevertheless, if demand does not pick up, the storage situation remains the same, and upcoming contracts could have similar price developments.

Alaska

At its most recent peak in 2012, oil and gas production taxes generated $6.15 billion in Alaska; rents and royalties brought in another $2.04 billion; the petroleum property tax contributed another $111.2 million; and the petroleum corporate income taxes added $568.8 million—with oil and gas taxes yielding $8.86 billion of the state’s $9.49 billion unrestricted general fund ($9.9 billion of $10.6 billion in current dollars), an astonishing 93 percent of the fund’s revenues. The oil industry supports more than 77,000 jobs according to the Alaska Oil and Gas Association.

Alaska’s Department of Revenue originally projected oil prices to average $63.54 in fiscal year (FY) 2020. In March, the Legislative Finance Division estimated that the price falls would add $300 million to the deficit in FY 2020 and $600 million in FY 2021. This now looks like an underestimation of the deficit.

This year, non-petroleum revenue stood at $502.9 million while petroleum revenues plummeted from an inflation-adjusted $9.9 billion to a projected $1.5 billion. In other words, Alaska was already thinking about reform when the coronavirus pandemic and dramatic decrease in oil prices hit. Alaska was under a stay-at-home order from March 27 to April 21. Restaurants and retail businesses expected to reopen today.

A freeze on nonessential business and devastation to the oil industry result in revenue projections for Alaska that are discouraging. To offset this deficit, Alaska’s legislature has agreed to withdraw $3 billion from the Constitutional Budget Reserve (CBR), which would take 70 percent of the reserves.

North Dakota

North Dakota’s 2019-21 biennium budget projected total oil and gas revenue of almost $5 billion based on an estimated price of $48 a barrel—$2.4 billion from the oil extraction tax and $2.4 billion from the oil and gas production tax. This month, the University of North Dakota estimated that the price drops would reduce tax revenue by 12 percent, including the effect from direct tax revenue and indirect tax revenue. This estimate was made when WTI was trading at $21 a barrel, but if the price slump continues, the effects could be worse. North Dakota has not implemented a stay-at-home-order—Governor Doug Burgum (R) instead has opted for a targeted approach that includes closing bars, restaurants, gyms, cinemas, and schools.

According to the North Dakota Department of Mineral Resources, production in North Dakota does not have much room for growth. That means the state, like Alaska, must start thinking about how to plan for an era of reduced oil revenue.

Overall, the coronavirus pandemic affects almost every source of state revenue, and with its duration unknown, predicting economic outcomes will be difficult. The impact on the oil industry is just one example in an unfortunately growing list of economic downturns. The industry supports tens of thousands of jobs across the country and this crisis could have a long-lasting impact on the communities supported by these jobs.

Source: Tax Policy – Historic Oil Price Burns Hole in State Budgets