Tax Policy – Treasury Audit Highlights the Need for Clearer Eligibility Guidelines for the EITC

Despite better record keeping, the federal government continues to incorrectly send out billions of dollars in tax relief, a sign of complexity in the tax code. Last Thursday, a Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration audit estimated that 25.3 percent ($17.4 billion) of the $68.7 billion Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) payments made in Fiscal Year 2019 were improper. The audit concluded that while there is better reporting of improper payments, there has been no significant reduction to the billions of dollars of improper payments.

Congressional lawmakers should consider simplifying dependent eligibility requirements, a major source behind the chronic issue of improper EITC payments. IRS officials should also use their power to double-check filers claiming the credit who have made erroneous claims in prior years.

EITC At-A-Glance

The EITC is a refundable tax credit equal to a fixed percentage of earned income up to a maximum credit amount. Tax credits provide a dollar for dollar reduction in tax liability. A refundable tax credit allows a taxpayer to receive a refund if the credit they are owed is greater than their tax liability.

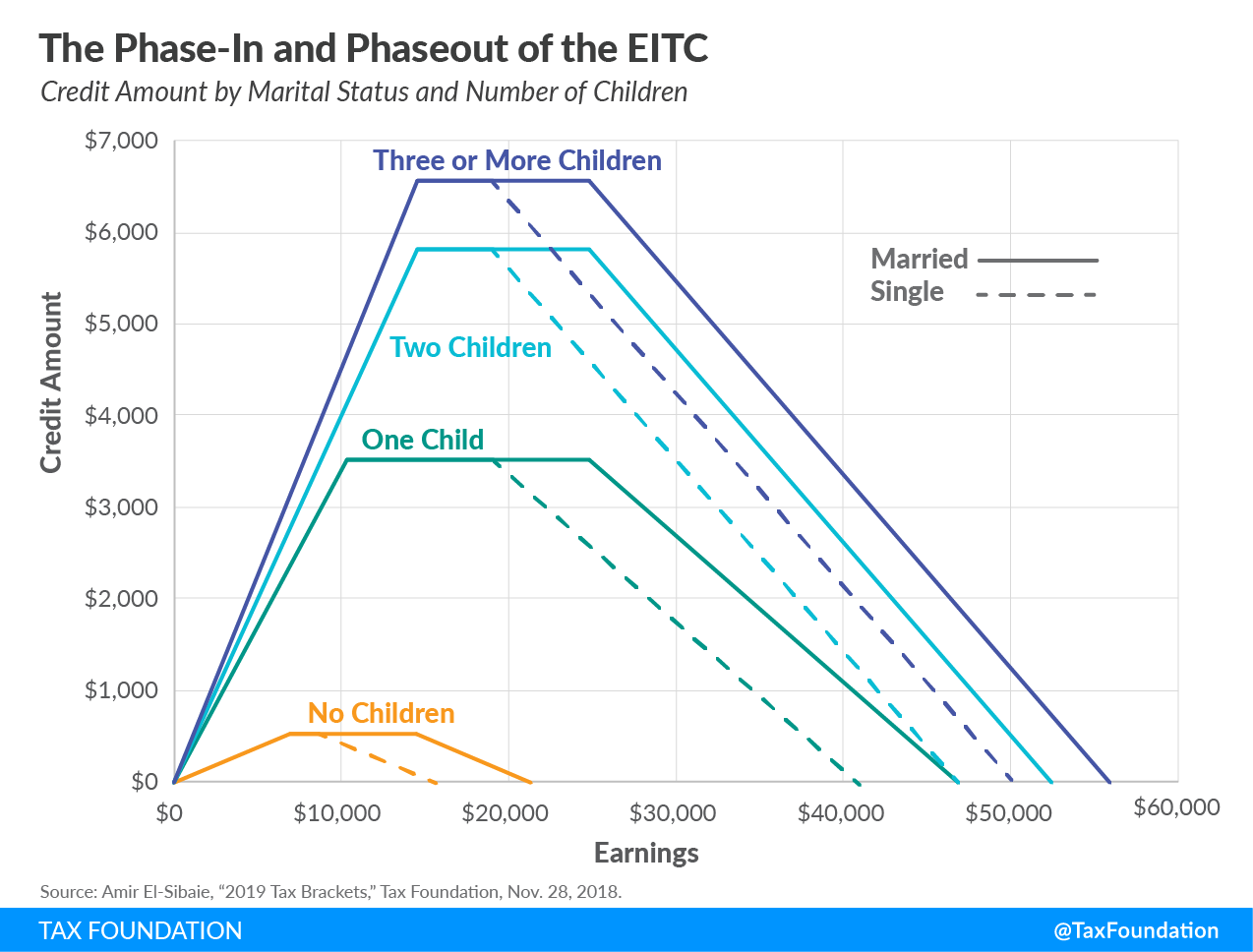

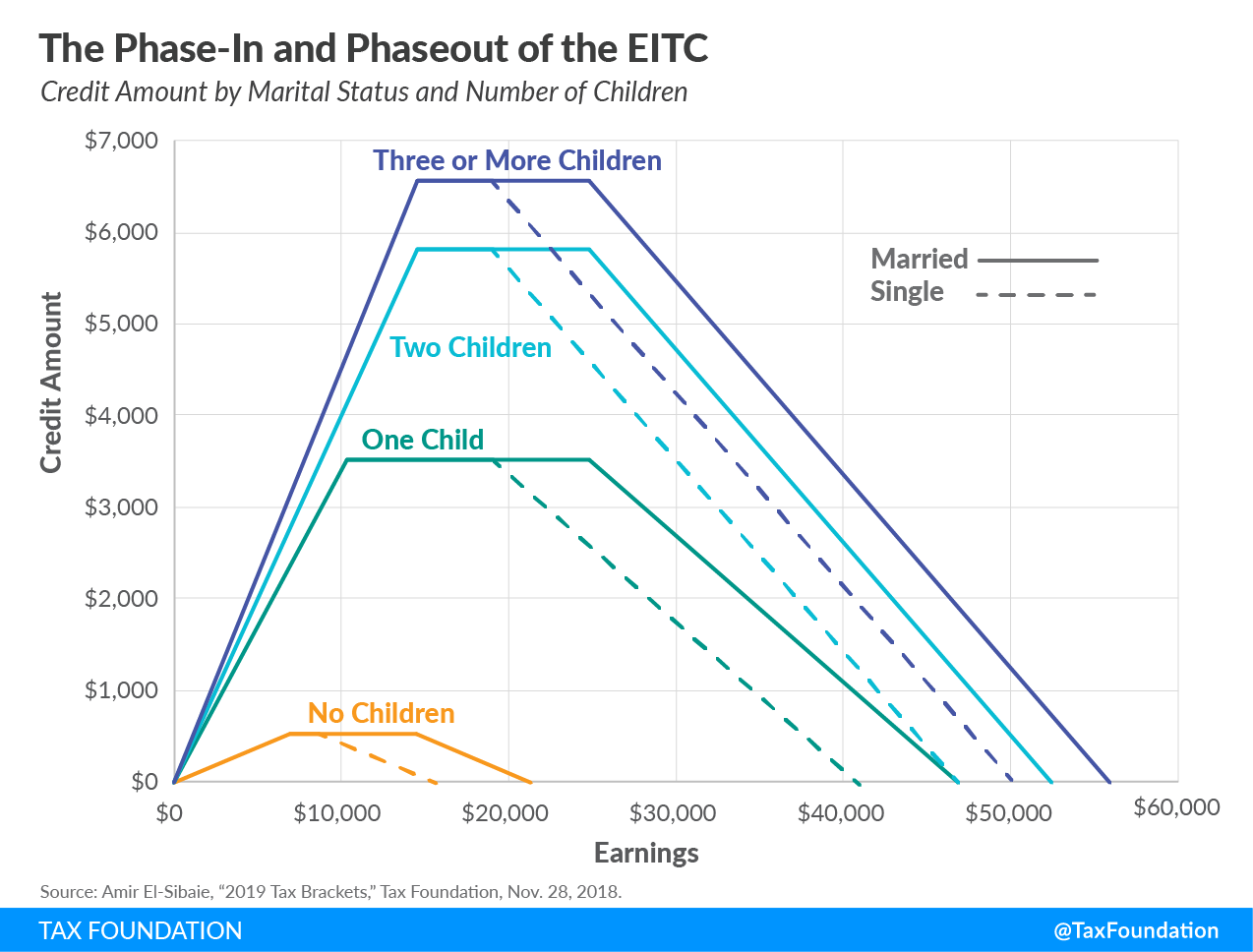

Currently, the EITC’s credit amount varies by income, number of children, and marital status (see chart below).

In the phase-in range, workers receive a credit for each additional dollar of income they earn, until it reaches the earned income amount, or plateau.

At the plateau, workers can receive the maximum credit but earning additional income does not increase the credit.

Once workers earn enough income to be in the phaseout range, the credit is reduced as they earn additional income, until the credit fully phases out to zero.

Explaining High Error Rates

The Treasury audit cited concerns from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) that the EITC program’s complexity may be one reason for ongoing improper payments.

As the Tax Foundation highlighted in a previous report, improper payments are largely a result of the same child being claimed multiple times due to shared custody agreements or other complex living situations.

Under current law, the amount of credit a person receives from claiming the EITC is dependent on three things: adjusted gross income (AGI), marital status, and number of children. Specifically, the EITC sets out certain dependent eligibility requirements based on relationship, age, and residence to determine the number of qualifying children:

- An eligible dependent must be the filers’ son, daughter, adopted child, stepchild, foster child, or descendent of any of them (e.g., a grandchild); and/or brother, sister, half-brother, half-sister, stepbrother, stepsister, or descendant of any of them (e.g., a niece or a nephew).

- The dependent must be younger than 19, or in the cases of full-time students, younger than 24.

- Those who are permanently and totally disabled also qualify.

- The dependent must also reside in the primary residence of the taxpayer(s) claiming the credit for more than half the year.

Critically, only one taxpayer may claim the dependent for tax-related benefits—although, as the Treasury report points out, this is hardly the case in reality. Given that the number of dependents is a key determinant in how much a person receives in EITC, this presents an important and ongoing administrative issue.

Additionally, the Treasury audit concluded that the IRS did not sufficiently use its oversight authority to ensure that those who had previously made erroneous claims could not receive the credit again unless they had been recertified that they met proper eligibility requirements. Specifically, the report stated:

The ineffective use of the various authorities provided in the Internal Revenue Code is a contributing factor in the high rate of improper payments. These existing legislatively granted tools include the authority to assess the erroneous refund penalty and require taxpayers to recertify that they meet refundable credit eligibility requirements for credits claimed on a return filed subsequent to disallowance of a credit, and the ability to apply two-year or 10-year bans on taxpayers who disregard credit eligibility rules. However, the IRS does not use these tools to the extent possible to address erroneous credit payments.

Part of the oversight difficulty likely is due to a lack of resources and to new technology. Even so, in the 10 years since Congress passed the first EITC oversight bill, the IRS has been unable to stem chronic disbursement of billions of dollars in incorrect payments.

Whether a result of unclear eligibility requirements or a lack of resources to properly review, the issue must be addressed. The consequence of not doing so would mean continued misappropriation of taxpayer dollars and government revenue to filers who either do not qualify or should not receive the credit due to other considerations (e.g., because of a ban on their file for repeatedly claiming the credit erroneously over multiple years).

Addressing the Problem

Among other proposals, former National Taxpayer Advocate Nina Olsen has suggested updating the definition and guidance of who constitutes a “primary carer” for purposes of determining who the dependent is actually dependent upon. This would include providing a checklist of duties a primary carer would perform and what follow-up documentation might be requested (i.e., school or medical records) if a child is claimed multiple times.

Concurrently, Treasury has recommended that the IRS use more of its already delegated powers to check filers who have made erroneous claims in prior years before sending out payments. Congress could also expand the IRS’ authority to fix filed returns during processing and give the agency more financing to update technology and increase manpower.

Given that the number of dependents is a key determinant in how much a person receives in EITC, this presents an important administrative issue. Currently, people who claim the EITC are more likely to be audited, creating undue burden on low-income taxpayers. Decoupling the number of dependents a worker can claim in order to receive the EITC and instead focusing on child-related benefits in the Child Tax Credit (CTC) could ensure that workers receive EITC assistance without the complexity of determining custody.

This proposal has also been suggested in a National Taxpayer Advocate report and by other tax policy scholars. Removing the household component of the EITC would decrease improper payments associated with the credit by making compliance easier for lower-income taxpayers and the IRS. Lawmakers could consider a proposal which focuses the EITC primarily around work and wages earned per worker while the CTC could focus on dependent benefits.

Conclusion

Improper payments mean that scarce resources are not properly reaching their intended recipients in the right amounts. A simpler credit structure would reduce complexity for taxpayers as they try to claim the credit and improve the administrability of the credit. The status quo is billions of dollars of improper payments and a complex credit structure for low-income taxpayers to navigate.

Source: Tax Policy – Treasury Audit Highlights the Need for Clearer Eligibility Guidelines for the EITC