Tax Policy – Advancing Net Operating Loss Deductions in Phase 4 Business Relief

Key Findings

- The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act provided economic relief to businesses in part by modifying net operating loss (NOL) deduction rules, expanding NOL carrybacks, and increasing NOL deductibility limits. Policymakers have an opportunity to build on these changes in Phase 4 of relief by advancing NOL deductions to firms that had limited taxable income, making it more likely they survive the economic downturn.

- Accelerating the tax benefit of NOL deductions will require careful design by policymakers to ensure the benefit is properly targeted to struggling firms and is simple to administer for the IRS and eligible businesses. Design choices include how accelerated losses are applied against firm tax rates, whether there should be a maximum accelerated NOL limit, which tax years when NOLs are accrued are eligible, and how to navigate the long-run revenue effects of accelerating NOL deductions.

- If successfully designed, accelerating the tax benefit associated with NOL deductions could be expanded to other tax assets, such as R&D tax credits or depreciation allowances, if additional liquidity is needed. Accelerating NOL deductions could also be combined with refinements to NOL changes in the CARES Act to ensure proper targeting, such as capping the maximum tax rate applied to NOL carrybacks to current law tax rates and reforming passive loss rules.

Introduction

The coronavirus crisis and related economic downturn has spurred policymakers to explore ways to provide targeted relief to businesses struggling to survive. As policymakers consider how businesses should be supported in the next phase of economic relief, there is an opportunity to build on net operating loss (NOL) provisions in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to ensure startups and firms without taxable income can also benefit from those changes.

Accelerating NOL deductions firms have accrued from prior tax years and giving them the tax benefit during the crisis will improve the likelihood that startups and newly launched firms survive, but policymakers will need to consider different design options to ensure the acceleration is appropriately targeted and is simple for firms to claim. This paper reviews how accelerating NOL deductions may be designed to help businesses in the next round of federal relief.

Why Net Operating Loss Deductions Matter, and Treatment Under Current Law

Net operating loss (NOL) deductions are built into the tax code so firms are taxed on average profitability over time and are not penalized for having volatile income or uneven earnings over different tax years.[1] Without NOL deductions, two firms that earn the same income but in different tax years may pay different effective tax rates.

For example, imagine a firm (Firm 1) that loses $50,000 in its first year, but earns $100,000 in the second year. A second firm (Firm 2) earns $25,000 in both years. In the absence of NOL deductions, the first firm is taxed at a 42 percent effective tax rate over those two years, while the second firm faces an effective tax rate half the size at 21 percent (see Table 1). The first firm faces a higher effective tax rate for earning uneven income over those two years.

| Year 1 Net income | Year 2 Net Income | Tax Liability for Year 1 | Tax Liability for Year 2 | Combined Effective Tax Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firm 1 | ($50,000) | $100,000 | $0 | $21,000 | 42% |

| Firm 2 | $25,000 | $25,000 | $5,250 | $5,250 | 21% |

|

Source: Tax Foundation calculations. |

|||||

When NOL deductions are available, both firms face an equivalent effective tax rate, and the firm with uneven income is not penalized for losses accrued in Year 1 (see Table 2). NOL deductions are an important aspect of the tax code to ensure neutrality between firms and industries that experience variability in profits over time.

| Year 1 Net income | Year 2 Net Income | Tax Liability for Year 1 | Tax Liability for Year 2 | Combined Effective Tax Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firm 1 | ($50,000) | $100,000 | $0 | $10,500 ($100,000 – $50000) * 21% | 21% |

| Firm 2 | $25,000 | $25,000 | $5,250 | $5,250 | 21% |

|

Source: Tax Foundation calculations. |

|||||

While NOL deductions move the tax code closer to neutrality, the tax code still treats NOLs less favorably than profits under current law. When a firm makes taxable income, it is taxed that year at the firm’s marginal tax rate. However, if a firm makes a loss, the firm may have to delay taking the tax deduction associated with the loss until income is earned in the future. In other words, “a business profit incurs an immediate tax liability, while a business loss does not always yield an immediate tax benefit.”[2]

The tax asymmetry faced by businesses with losses means that firms are penalized for losses in the tax code. Firms must “carry over” losses accrued in any given tax year to future years, when they may use those deductions to offset or reduce taxable income. The longer a firm must wait to deduct an NOL deduction from future taxable income, the smaller the tax benefit the firm receives.[3] This is because inflation erodes the value of NOL deductions over time, and the tax benefit would be more valuable today than if it is taken in the future (the time value of money).[4]

Review of CARES Act NOL Provisions and Limitations for Business Relief

The CARES Act provided economic relief to individuals and businesses struggling during the coronavirus pandemic.[5] As part of this relief, NOL deduction rules were modified to provide additional liquidity for businesses that may otherwise lay off workers or shut down permanently due to the downturn in economic activity.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 eliminated NOL carrybacks, which permitted firms to apply NOL deductions to taxable income earned in two previous tax years. Instead, the TCJA permitted firms to carry forward NOLs indefinitely to offset taxable income in future tax years. Because firms could no longer use accrued NOLs to offset income from previous tax years, they would have less liquidity during downturns when they accrue losses that cannot be carried back to profitable tax years. This undermines a firm’s ability to survive during a downturn.[6]

The CARES Act provided a five-year carryback for losses earned in 2018, 2019, or 2020, reinstating the carryback temporarily.[7] The CARES Act also suspended the NOL limit of 80 percent of taxable income, which means that firms may deduct their NOLs to eliminate all of their taxable income in a given tax year.[8] Additionally, pass-through owners may use firm NOLs to offset their non-business income above the previous limit of $250,000 (single) or $500,000 (married filing jointly) for 2018, 2019, and 2020.

Each of these changes to NOL deduction rules is intended to quickly give businesses more liquidity during the downturn. This is especially true of the carryback provisions, which let firms claim a tax refund immediately by amending tax returns from prior years with loss deductions on their books.

While these changes give firms with losses more breathing room, firms must have net income in the last three tax years to deduct these losses and realize a tax benefit. Many firms, such as startups and recently launched small businesses, may not have been operating in these tax years or may have run losses with the goal of reaching profitability in the future. These firms may also have accrued NOL deductions, but do not have an opportunity to use them. Additionally, many firms may have accrued losses above the amount of taxable income that can be offset through carrybacks in the eligible years.

Phase 4 relief is an opportunity to extend the relief provided for other businesses to startups and newer small firms while limiting the penalties imposed on losses in the tax code. One option to make up for the limitations contained in the CARES Act NOL provisions is to allow firms to “cash out” or monetize their NOLs and receive a tax refund in return. This accelerates deductions that would have to be taken in the future while providing needed relief to firms that do not benefit (or do not benefit enough) from the NOL changes in the CARES Act.

Design Considerations when Advancing NOLs

Policymakers will have several options when considering how to advance accrued NOL deductions to firms. Relief provided through an NOL advance should be: 1) targeted to firms that are most likely to be struggling during this crisis, 2) simple to administer and understand, and 3) consistent with an improved treatment of losses in the long run. Policymakers may also consider the revenue effects of advancing NOLs and design the relief to be consistent with long-run revenue goals.

Applying NOL Deduction Advances to Corporate and Pass-through Firm Tax Rates

One of the first items policymakers must consider when designing an NOL advance is what tax rate will apply when an NOL is redeemed by C corporations and pass-through firms (such as sole proprietors, S corporations, and partnerships).

The tax rate applied to NOL deductions for C corporations is straightforward, as these firms face a flat 21 percent corporate income tax. Advancing the NOL deduction at 21 cents per dollar is consistent with how losses are treated under current law. However, pass-through owners face progressive individual income tax rates that rise with net income.

There are two ways to apply the NOL advance for passthroughs: apply all NOLs at the top marginal individual income tax rate of 37 percent or apply NOL deductions through the increasing brackets in the individual income tax rate schedule. The latter option would allow pass-through firms to apply their first $9,875 in NOLs ($19,750 if filing jointly) at a 10 percent tax rate, the next $30,250 of NOLs at 12 percent, and so on until reaching the top income tax rate of 37 percent after advancing $518,400 worth of NOLs.[9]

Applying all NOL deductions advanced to the top income tax rate for pass-through firms would provide the maximum amount of liquidity for firms by increasing the value of NOLs accrued before the top marginal tax rate applies. This would tend to benefit firms with fewer NOLs the most. For example, a firm with $500K in NOLs would be able to deduct all at a 37 percent tax rate instead of rates in the lower brackets under current law, while a large passthrough with $5 million in NOLs would only see an additional benefit for the first 10 percent of its NOLs (about $500K) before hitting the top marginal tax rate.

Policymakers may not want to increase the value of accrued NOLs compared to current law. To do so, NOL advances could be applied through each increasing individual income tax bracket. This would also lower the cost of the proposal while ensuring that NOLs have consistent value by income level when firms deduct NOLs normally.

Relief Limitations

To ensure smaller firms are the primary beneficiaries of NOL deduction advances and the cost of the proposal is limited would be to impose limits on the amount of NOLs that can be advanced or impose a maximum firm size to qualify for the relief. Alternatively, policymakers could explore limiting the advance to a percentage of the NOL tax benefit.[10]

A clean way to limit the relief is to impose a maximum amount of NOL deductions that may be advanced to each firm. For example, firms may be allowed to only advance $100 million worth of NOLs before being required to abide by current law on additional NOLs. This would constrain the amount of NOLs being used overall while still providing relief for small to medium-sized businesses.

Policymakers could impose eligibility requirements on which firms may be allowed to advance NOL deductions currently on the books. For example, many of the relief provisions in the CARES Act used a 500 full-time equivalent employee limit for firms to qualify. While this could ensure smaller firms get access to NOL advances, this may deprive some medium-sized or larger firms from receiving liquidity even if they are struggling to remain open. This would also introduce complexity into the relief, making it more likely that firms try to use nuances in the provision to qualify, as has happened in some of the CARES Act-related relief programs like the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP).[11] Imposing a broad NOL advance limit for all firms would be a better and simpler way to target the relief.

So far, this proposal has assumed that the value of NOL deductions would remain at 100 percent when they are advanced to firms. Alternatively, the value of the NOLs could be reduced (to say, 50 percent).[12] This would reduce the cost of the relief but would also reduce how much benefit the NOLs advance would have for firms. For example, a firm with $50,000 in NOL deductions may advance them for $25,000 worth of losses. Applied at a 21 percent tax rate, the firm would receive a $5,250 tax benefit as opposed to a $10,500 tax benefit if the firm waited to deduct the loss normally. This may incentivize some firms to hold onto accrued NOLs for use in future tax years to maximize their value while reducing the benefit for NOLs that are advanced.

Similarly, the NOL advances could be subject to an interest charge that would be paid back to the federal government in future years.[13] This would also reduce the value of NOL deductions advanced now, though it would spread that cost out over time. An interest charge may also introduce additional complexity into firms’ tax reporting, especially for smaller firms. Reducing the value of the advanced NOL deduction directly would be simpler to administer than an interest charge.

Revenue Effects of Advancing NOLs

The impact of advancing NOL deductions on revenue is important to consider as policymakers keep an eye on the growing U.S. deficit and debt coming out of the crisis. While detailed net operating loss data is not easily accessible, broad data on historical NOLs provides a rough sense of the gross cost of advancing NOL deductions.

An important aspect to consider when accelerating NOL deductions is the difference between the gross outlay that the federal government will experience when it processes NOL advances and the net cost to federal revenue over time. For many of the NOL deductions, the advance is merely changing the timing of when the NOL is realized. For example, a firm advancing $50,000 in NOL deductions in tax year 2020 will not be able to use those deductions in 2021 or 2022, when it will have to pay tax on taxable income earned. This will recoup some portion of the gross outlay over time.

The primary cost to the federal government will be borne by firms advancing NOL deductions in 2020 but end up going out of business prior to earning the taxable income required to offset the cost of the advance. This is likely to be a larger effect in an economic downturn than in expansions. Often, a firm’s tax assets are inherited by other firms in the bankruptcy process, which may help reduce the net cost imposed by firms that go out of business, but we would not expect this to offset all the costs imposed by creating an NOL advance.

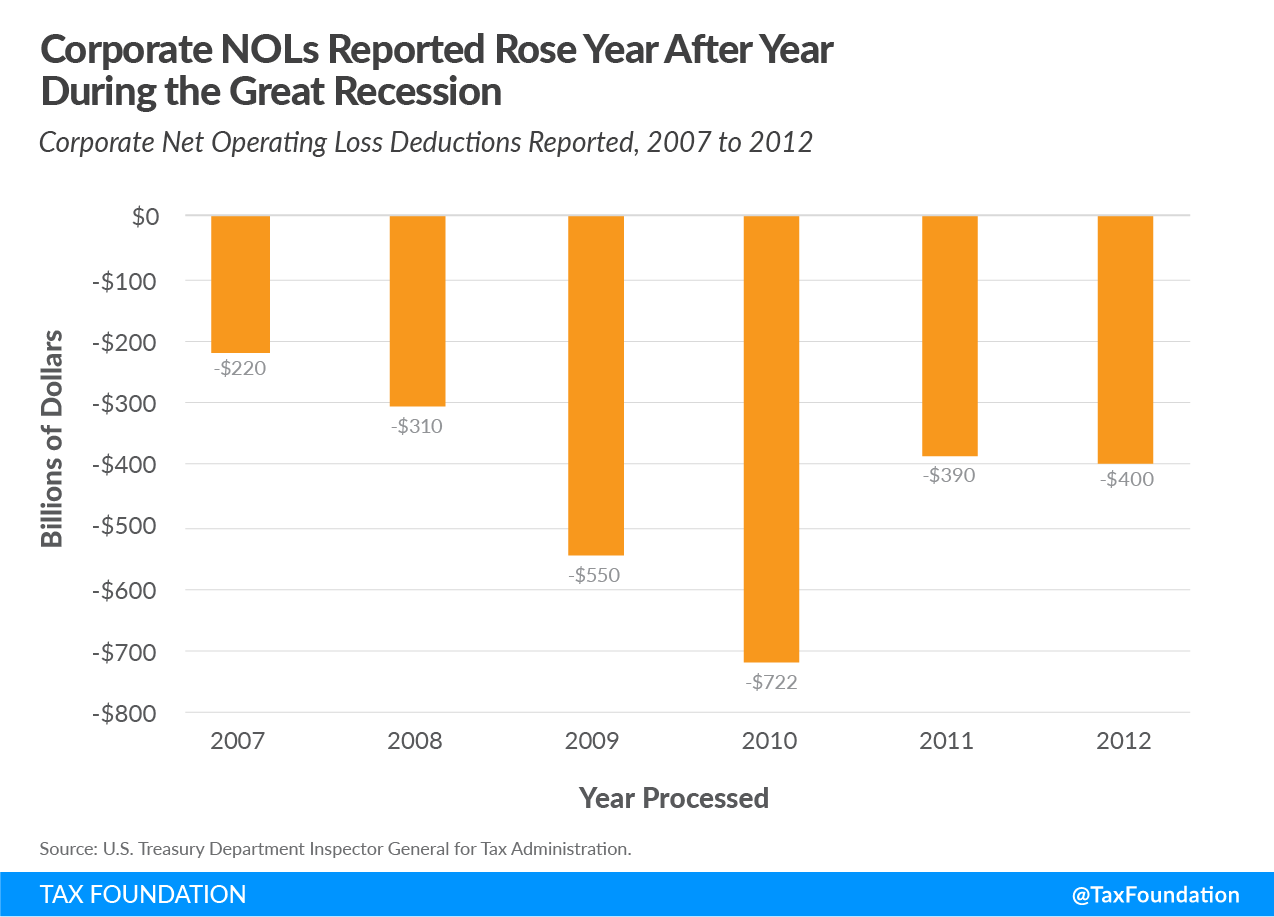

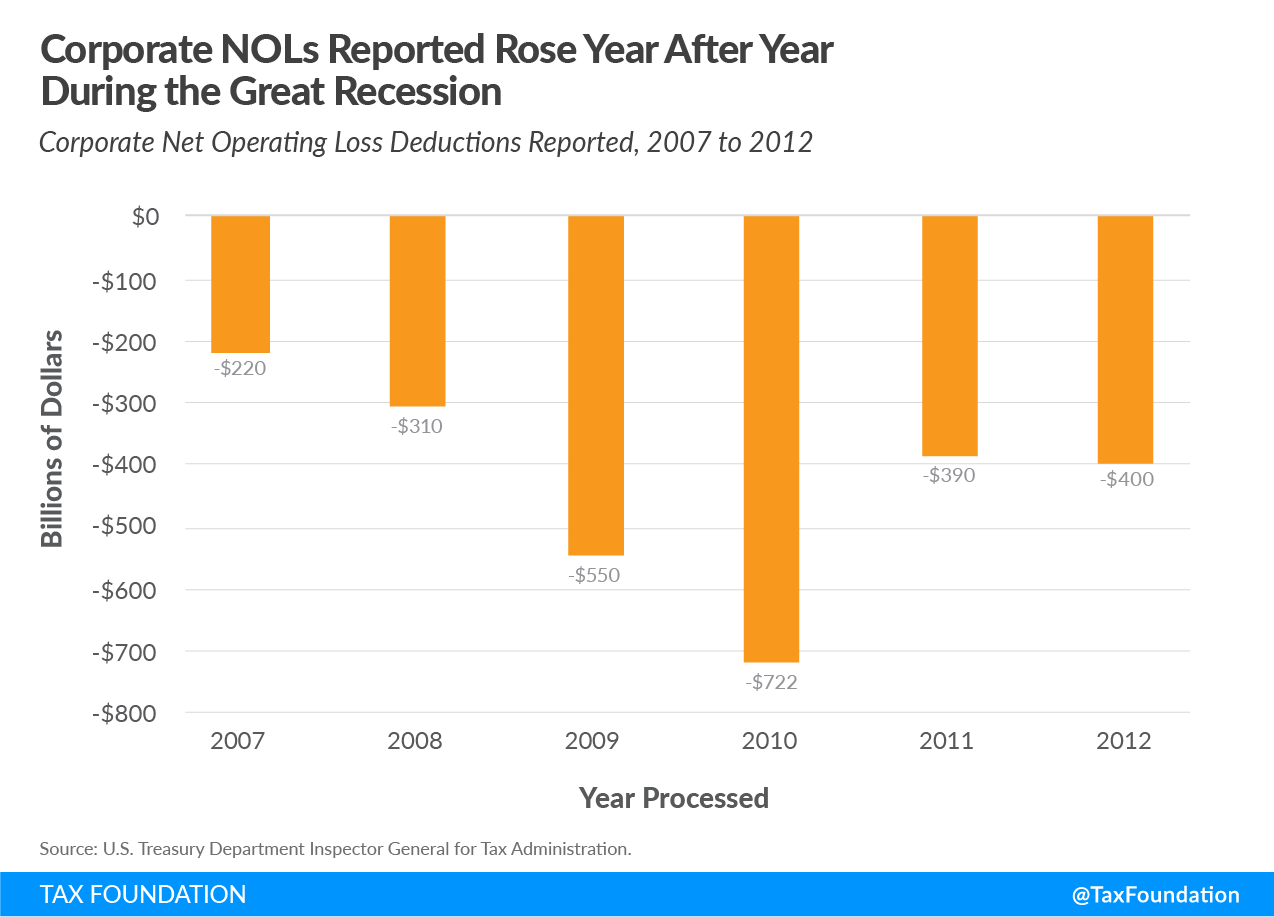

For a sense of potential gross outlays during the current downturn, we can look at losses accrued in prior tax years where data is available. For example, in the Great Recession, losses for corporations rose from about $225 billion in the 2007 processed year (PY) to about $722 billion in PY 2010 (See Figure 1).[14] NOLs tend to rise rapidly during economic downturns, and NOLs will likely rise in the 2020 and 2021 tax years.

In addition to adopting a maximum NOL limit, policymakers should consider limiting the advance to NOLs accrued over specific tax years. This would limit the cost, as it would not make the entire stock of accrued NOLs eligible for an advance but only NOLs earned in specific tax years. Making NOLs earned in 2020 or 2021 ineligible would prevent the cost from rising prohibitively due to the downturn while preventing firms from earning losses in order to advance them today.

While more recent NOL data is not available on an economy-wide basis, data from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) on previous tax years is informative. Deficits for all firms were about $915 billion in tax year 2015, the most recent tax year with data available.[16] This includes about $400 billion in deficits for C corporations and $515 billion for pass-through firms. Changes to tax law as the result of TCJA make it challenging to estimate NOLs accrued for 2018 and 2019. Before applying tax rates to the accrued losses, the gross outlay associated with advancing NOLs would have to be adjusted downward from the NOLs accrued for those years to account for NOLs used in the time since they were accrued and to account for firms that would prefer to keep their NOLs for future tax benefit.

When combined with the timing effect, there may be a large gap between the aggregate amount of NOLs accrued over eligible tax years and the net cost to long-run federal revenue. Policymakers concerned with the impact of this proposal on deficits should consider options to limit NOL eligibility.

Other Considerations for NOL Deduction Changes in Phase 4 Relief

The changes made to NOL carrybacks and to limitations governing NOL deductions for non-business income in the CARES Act met criticism for providing a windfall for high-income taxpayers and providing arbitrage opportunities by letting firms offset net income at higher tax rates that existed prior to the TCJA.

Accelerating NOL deductions could be paired with efforts to eliminate arbitrage by capping NOL carrybacks at current tax rates (21 percent vs. 35 percent for corporations carrying back to the 2017 tax year, for example) and considering how passive loss rules should be modified to prevent inappropriate use by high-income individuals.

Other tax assets could also be advanced in a similar way as net operating losses. For example, R&D tax credits or other tax assets on firms’ books could be accelerated to provide additional liquidity. One wrinkle with extending this treatment to other tax assets, however, is that they are not as broadly owned as losses are for firms, and the ownership of tax assets like R&D credits may not be as tightly correlated with economic need as the accrual of net operating losses would be. Policymakers should consider proposals to accelerate other tax assets carefully to balance the need for liquidity with effective targeting for struggling businesses.

Conclusion

There is an opportunity to build on the CARES Act’s economic relief provisions for businesses in Phase 4. A compelling option is to give firms the ability to accelerate their net operating loss deductions, which provides additional liquidity to businesses that did not benefit from NOL changes in the CARES Act due to a lack of taxable income.

Policymakers will have to consider design options for accelerating NOL deductions to ensure the refunds are simple, provide targeted relief to struggling firms, and are consistent with long-run revenue needs. If successfully implemented, this proposal would show how the tax treatment of net operating losses could be improved for the long run, reducing the tax code’s penalty for business losses.

[1] Garrett Watson, “A Review of Net Operating Loss Tax Provisions in the CARES Act and Next Steps for Phase 4 Relief,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 14, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/phase-4-relief-legislation-net-operating-loss-cares-act/.

[2]Garrett Watson and Nicole Kaeding, “Tax Policy and Entrepreneurship: A Framework for Analysis,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 3, 2019, 11, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-policy-entrepreneurship/. See also Huaqun Li, “A Quick Overview of the Asymmetric Taxation of Business Gains and Losses,” Tax Foundation, May 31, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/taxation-business-gains-losses-nol/.

[3] Kyle Pomerleau, “The Tax Code as a Barrier to Entrepreneurship,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 15, 2017, 2, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-code-barrier-entrepreneurship/.

[4] Ibid.

[5] See generally, Garrett Watson, Taylor LaJoie, Huaqun Li, and Daniel Bunn, “Congress Approves Economic Relief Plan for Individuals and Businesses,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 30, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/cares-act-senate-coronavirus-bill-economic-relief-plan/.

[6] William Gale and Yair Listokin, “The Tax Cuts Will Make Fighting Future Recessions Complicated,” The Hill, Feb. 23, 2019, https://thehill.com/opinion/finance/431284-the-tax-cuts-will-make-fighting-future-recessions-complicated.

[7] Garrett Watson, “A Review of Net Operating Loss Tax Provisions in the CARES Act and Next Steps for Phase 4 Relief.”

[8] Ibid.

[9] Amir El-Sibaie, “2020 Tax Brackets,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 14, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/2020-tax-brackets/.

[10] William C. Barrett, “How Cash Advances Equal to NOL Deductions Could Work,” Tax Notes, Letter to the Editor, Apr. 6, 2020, https://taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today-federal/exemptions-and-deductions/how-cash-advances-equal-nol-deductions-could-work/2020/03/31/2cbyb.

[11] Danielle Kurtzleben, “Not-So-Small Businesses Continue To Benefit From PPP Loans,” National Public Radio, May 4, 2020, https://npr.org/2020/05/04/850177240/not-so-small-businesses-continue-to-benefit-from-ppp-loans.

[12] For a more detailed example, see William C. Barrett, “How Cash Advances Equal to NOL Deductions Could Work.”

[13] Ibid.

[14] “The Internal Revenue Service Administered Corporate Net Operating Losses Efficiently and Effectively; However, Financial Reporting Could be Improved,” U.S. Treasury Department Tax Inspector General for Tax Administration, Oct. 13, 2015, 6-7, https://treasury.gov/tigta/iereports/2016reports/2016IER002fr.pdf.

[15] The “Year Processed” in Figuret 1 shows transactions for the prior tax year. For example, NOLs processed in 2010 were primarily in returns for the 2009 tax year.

[16] Deficits as reported by IRS Integrated Business Data do not necessarily match net operating losses reported, as firms may be in deficit for reasons other than operating losses. However, they are broadly consistent with NOL data that is available, such as when comparing corporate NOLs reported for PY 2007 to 2012 by Treasury and corporate deficits as reported by IRS. See Table 1 in “SOI Tax Stats – Integrated Business Data,” Internal Revenue Service, https://irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-integrated-business-data.

Source: Tax Policy – Advancing Net Operating Loss Deductions in Phase 4 Business Relief