Tax Policy – Digital Tax Deadlock: Where Do We Go from Here?

The growth of the digital economy over the last several decades has raised important questions about how to tax corporations that no longer need a physical presence in a country to turn a profit there.

For months, countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have been working towards a multilateral solution to this challenge, with the goal of developing a new international tax framework by the end of 2020.

Now, the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, the U.S.’s call for a pause to OECD talks, and unilateral actions across the world threaten to derail the initiative and spark a harmful tax and trade war.

We recently hosted an exclusive Talking Tax Reform webinar discussion to get up to speed on recent developments and gain insight from leading international tax experts on some of the following questions:

- What is the OECD trying to achieve with its digital tax project, what progress has it made, and why is the initiative so important for the U.S. and global economies?

- Why did the U.S. suggest a pause in negotiations and what does it mean for the OECD project?

- The U.S. Trade Representative has announced Section 301 investigations into unilateral digital services taxes (DSTs) in nine countries and the EU, in addition to an earlier investigation aimed at France—why are DSTs problematic and what‘s the risk that disputes devolve into a global tax and trade war?

- Is it possible to get the OECD project back on track and, if so, what’s the best path forward towards a multilateral agreement? If not, where do we go from here?

Tax Foundation President Scott Hodge moderated the panel discussion, which included:

- Cathy Schultz, Vice President, National Foreign Trade Council

- Daniel Bunn, Vice President of Global Projects, Tax Foundation

- Robert Stack, Managing Director, Deloitte Tax LLP, International Tax Group

I’m going to talk about two important issues to set the stage for our discussion about what we might expect from policy in the near future.

The first issue is the rise of digital technologies that obviate the need for local offices in countries around the world. Businesses can use digital tech to reach across borders and into markets without needing local employees, offices, or operations. This is where taxable physical presence and nexus shows up in policy concerns.

In 2017, there was nearly $30 trillion worth of e-commerce, the majority of that businesses selling to other businesses. The geography of internet users doesn’t track with the production locations of valuable computer software and platforms. Most of the value production occurs in North America, and the internet user base is skewed toward Southeast Asia. Policy responses to this include digital services taxes, virtual permanent establishment policies, and the OECD’s Pillar 1 approach.

The second issue is the rise of intangible assets—software, patents, and so on—as significant value drivers in the global economy. Intangible assets, by their nature, can be moved from one jurisdiction to another without the trouble that, say, uprooting and relocating a factory would create. In 2018, intangible assets made up 80 percent of the asset value of S&P 500 companies.

These intangibles are often shifted to lower-tax jurisdictions. This motivates a discussion of minimum taxation like the U.S. GILTI, and the OECD’s Pillar 2 GloBE proposal.

With those two baseline issues, physical presence and the rise of intangible assets, I’ll give a few examples of policy responses and discuss the economic implications.

The more and more that businesses can reach their clients virtually, the less likely there will be local permanent establishments for foreign countries to tax.

In short, this has led to two major policy directions:

- Digital services taxes

- New corporate income tax rules

Behind these policy directions is a key division in the digital tax debate.

Do you change the rules just for a few digital companies or should you try to make broad changes that affect other companies that aren’t necessarily digital but have digitalized business models?

The digital services tax takes the narrower approach. It is a tax on gross revenues of certain, defined, digital services.

The French digital services tax has a 3 percent rate and applies to revenues connected to provision of a digital interface or advertising services based on users’ data. It only applies to businesses with more than €750 million in global revenues and €25 million in France. This model is being replicated in dozens of countries across the world.

The problem with this approach to taxation is twofold.

First, gross revenue taxation cannot be a proxy for corporate income taxation. Revenue taxes are regressive. If you have a 6 percent profit margin, the digital services tax is a 50 percent profits tax. If you have a 3 percent profit margin on your digital activities in France, the 3 percent digital services tax taxes all of that away, essentially a 100 percent profits tax. If you are running losses in France, you still have to pay the digital services tax. Just for context, the French corporate income tax rate is about 32 percent.

Some countries claim that digital companies are under-taxed and see the digital services tax as a solution. However, the evidence those claims are based on doesn’t actually support the conclusion that digital companies are under-taxed. Rather, it shows that countries have tax preferences for the digital firms in the form of patent boxes and research and development subsidies. The problem these countries have is where the companies are taxed, and they have chosen to change the rules unilaterally using a discriminatory and punitive tax.

If the digital services tax is, in theory, paid in lieu of corporate income tax, it is a horrible proxy because it is a gross revenues tax.

Second, these are targeted, narrow policies.

Tax policy should not be designed on an industry-by-industry basis or with special rules for big vs. small players. Yet, these policies do exactly that. They identify specific digital activities or business models, separate large from small businesses, and tax them in a regressive manner with what looks like a protectionist intent.

That protectionism comes out pretty clearly when you have the tax policy leaders in the UK, France, Italy, and Spain suggesting to the U.S. Treasury Secretary that digital taxation is connected to the “free access” that digital companies have to the European market. The digital services tax essentially works like a tariff.

Another approach to solving the no local physical presence challenge has been to change definitions of permanent establishment. If instead of only taxing a business if it has employees or operations in your country, you could write rules to tax a business based on virtual presence.

Basically, if a company has lots of contracts in your country or lots of sales in your country through digital means, these new rules would treat that business as having a virtual permanent establishment. Countries such as Slovakia, Israel, India, and Nigeria have looked at this sort of approach.

And that is one of the areas the OECD is working on in Pillar 1 with a goal of redefining taxable nexus based on a new approach. The OECD approach in Pillar 1 would change where companies pay taxes, but only large, highly profitable companies, and only companies in certain sectors, namely automated digital services and consumer-facing businesses.

In recent weeks we have learned that some countries want to start with just the automated digital services part of that approach. Essentially, we’re back to the problems with the digital services tax: a narrow policy designed for just certain large businesses and only certain types of activities.

And that narrowness comes into conflict with countries that want a broader approach to changing international rules. The United States has advocated for that broader approach, notwithstanding the Pillar 1 safe harbor proposal, and has been met with calls focused more narrowly on digital companies.

That covers the first issue – the rise of digital technologies that undermine the need for local offices in countries around the world.

The second issue is the rise of intangible assets—software, patents, and so on— as significant value drivers in the global economy. Dozens of countries across the world have adopted patent boxes or similar incentives to attract those assets. In many cases the patent boxes give a 50 percent or greater discount off the corporate tax rate.

Many recent policy changes require the research and development activities associated with that software to occur in the same jurisdiction for the business to benefit from the corporate rate discount. The lower level of taxation still occurs and can distort where patents are owned and where research and development activities occur.

So, what are countries looking at to tax the shifting nature of intangible income?

They’re looking at the U.S. model. The U.S. now has a minimum tax on foreign intangible income—we call it GILTI for short—and it was adopted in 2017 as part of tax reform. Other countries are interested in having a similar policy agreed to at the global level. This is where Pillar 2 of the OECD approach comes in.

It’s worth mentioning here that the OECD has estimated the combined effect of Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 to be a net tax increase of $100 billion. There are challenges with that estimate, not least of which is that it relies on data recorded before lots of policy changes, including U.S. tax reform. So that number has a wide error band and could be much less of a meaningful revenue raiser and more likely a meaningful compliance and coordination headache.

What’s at stake with all of these competing proposals? For one, the potential for a global tax and trade war. The digital services taxes are likely to spark that war because of their narrow, discriminatory approach. The multilateral discussions at the OECD are meant to achieve a common approach rather than erecting new tax and trade barriers.

However, even in the multilateral discussion at the OECD another risk is a shift in international tax policy from broad rules and principles to narrow rules that lead to new distortions in multinational activities.

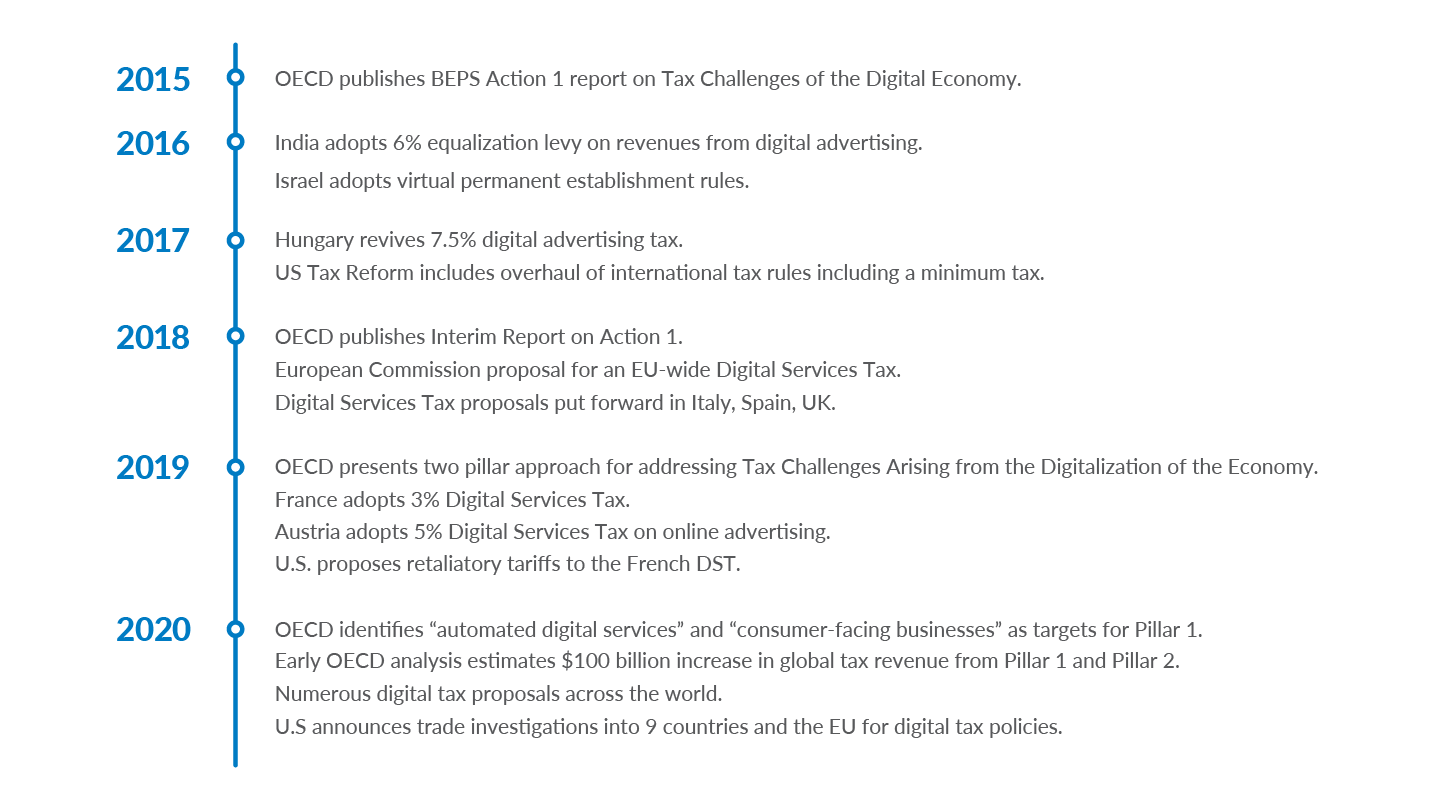

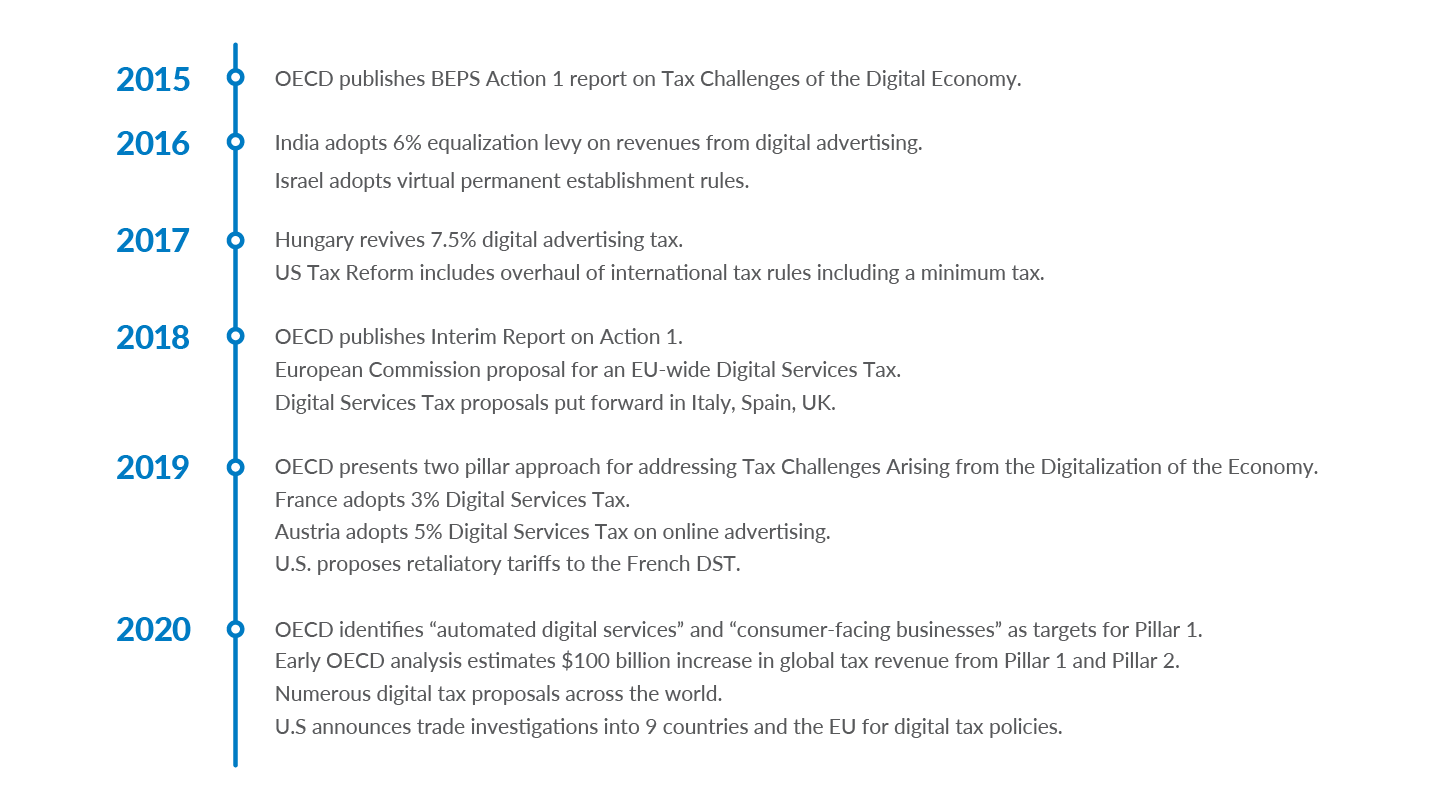

Over the last several years, there have been lots of new developments in digital tax.

Digital Tax Policies Are Becoming Increasingly Common and Controversial

There have been both unilateral and multilateral elements over the years.

Action on the policy front is clearly accelerating, but policymakers should examine these policies against sound principles for tax management.

If international tax policy becomes unilateral and reactionary, it will very likely become unstable, less transparent, more distortionary, and even more complex than what we have right now, and this would become a drag on global growth right at a time when the economy is incredibly weak.

If you are new to the Tax Foundation’s work, you can learn more about who we are and what we do here. You can also subscribe to our weekly newsletter and support our work here.

Source: Tax Policy – Digital Tax Deadlock: Where Do We Go from Here?