Tax Policy – Decades in Corporate Taxation

Corporate taxation has evolved significantly over the last several decades. Corporate income tax rates have come down significantly. Countries have redesigned their tax bases by changing the treatment of losses, interest, and capital costs. International tax rules have also been overhauled.

A new report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) provides a broad overview of the current corporate tax landscape and the most recent data. The report is part of the OECD’s effort to provide data in connection with Action 11 of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Project.

Corporate tax policies can vary significantly from one jurisdiction to another, creating incentives for businesses to invest and expand employment where their after-tax profits are higher. Those policy differences can also distort where profits arise, especially for profits from intangible assets such as patents, software, and brands.

Trends in Corporate Revenues and Rates

At the start of a new decade it is important to use the data to take stock of where things stand on corporate taxation. So, what are the key takeaways from the OECD’s latest report?

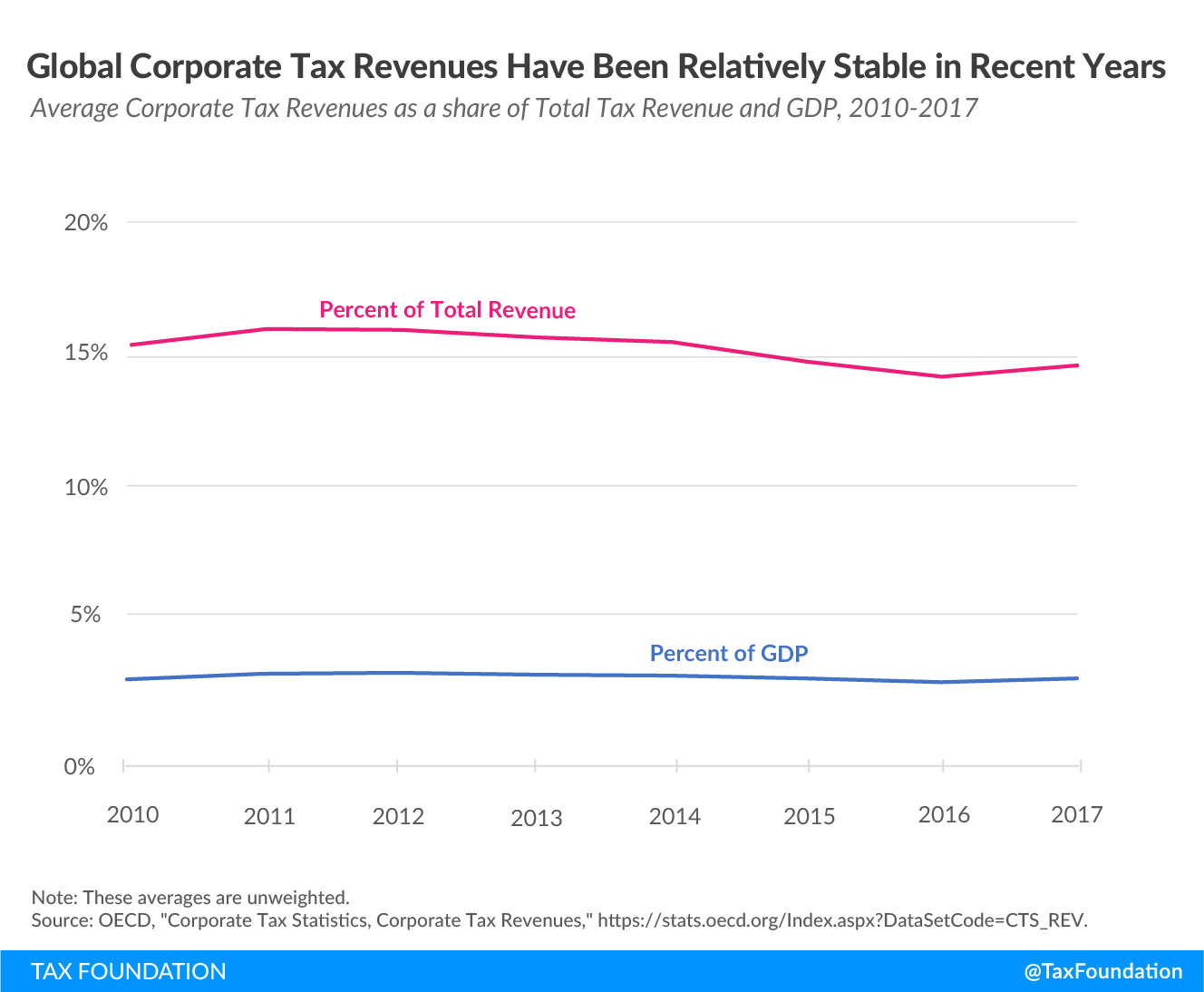

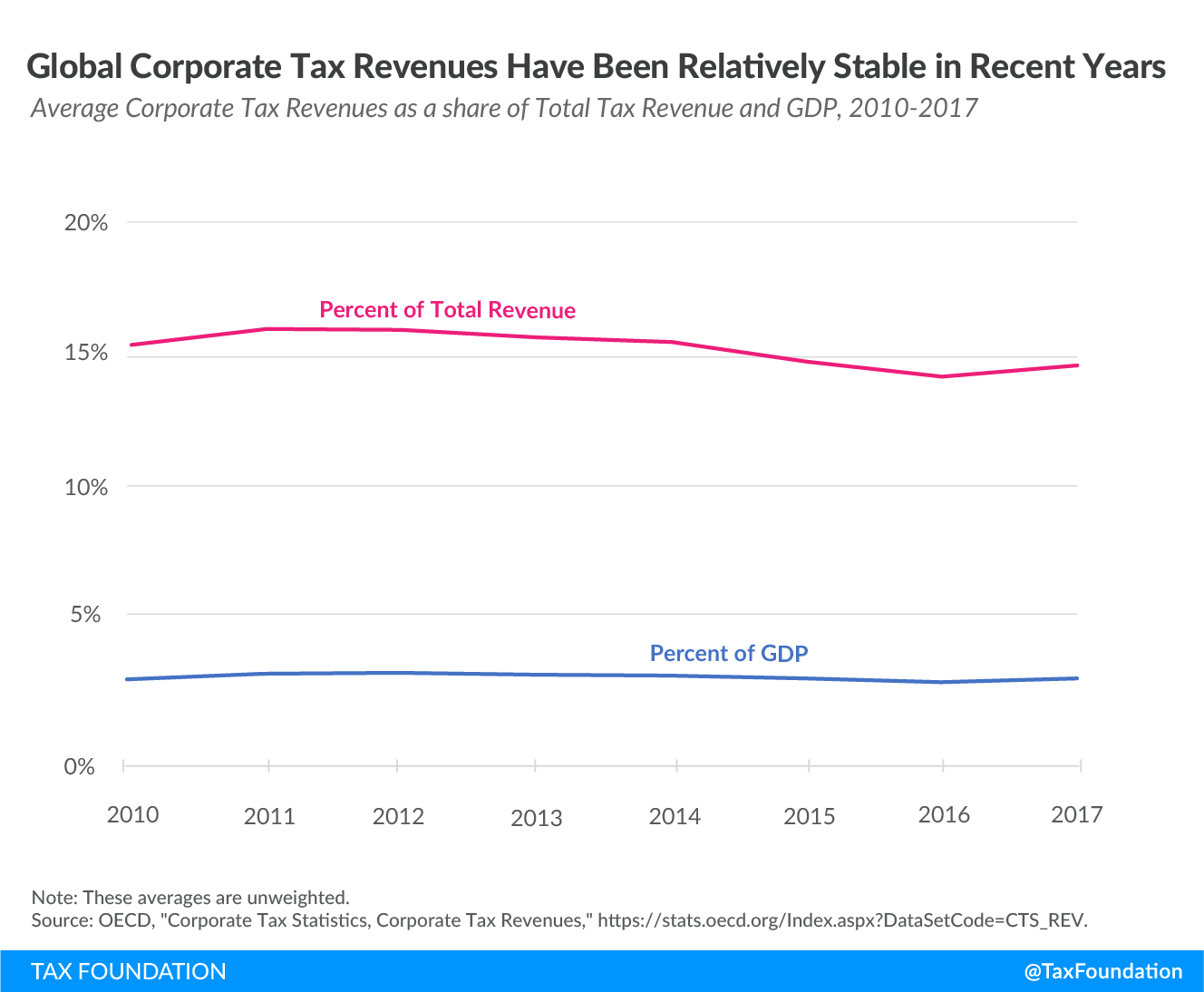

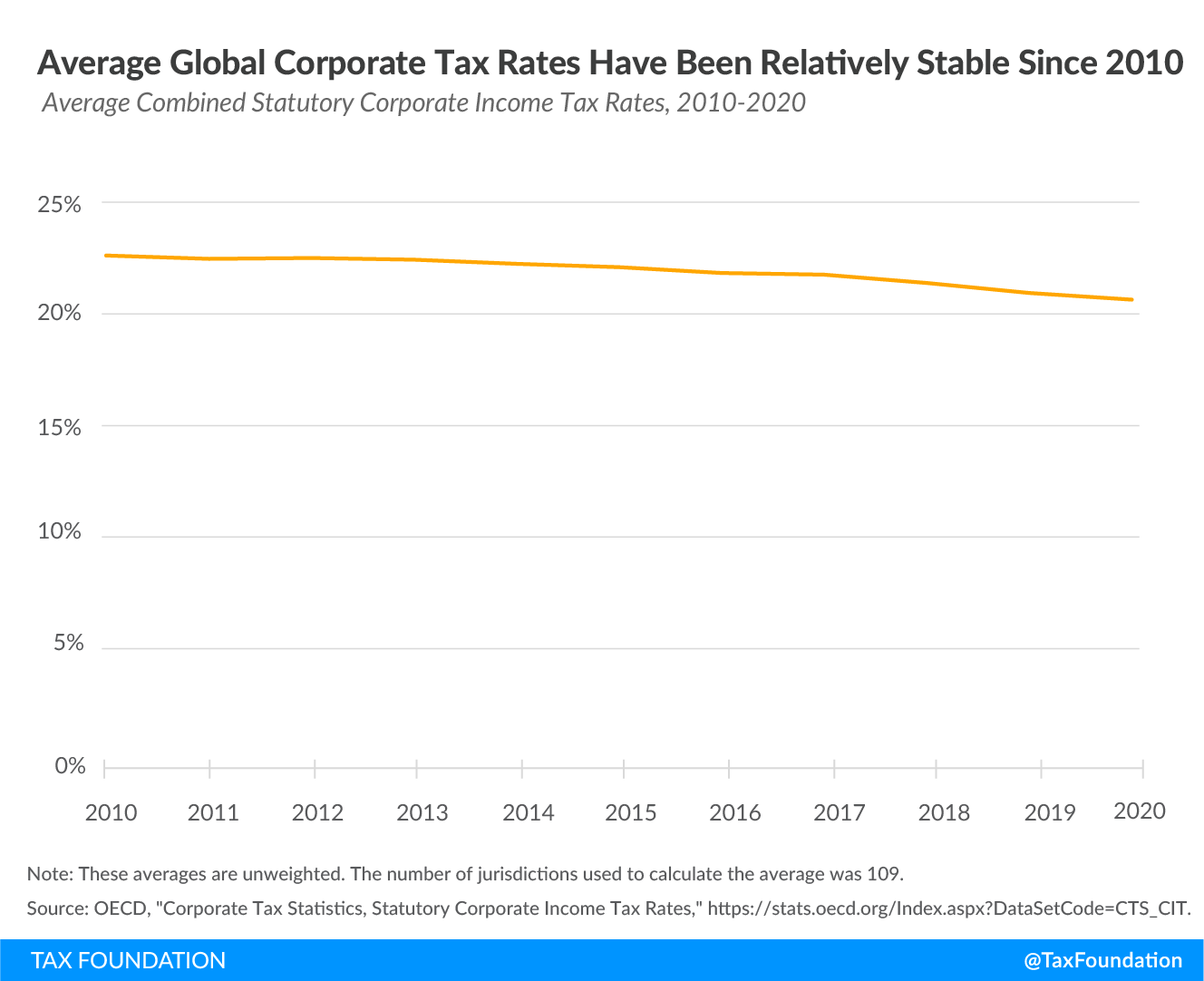

One main takeaway is that corporate tax revenues and rates have been relatively stable (on average) in recent years even after some major shifts in those averages before 2010.

Both as a share of GDP and share of total revenue, corporate taxes have been a consistent contributor to tax revenues over the last decade. Average statutory corporate tax rates fell by 7.4 percentage points from 28.0 percent in 2000 to 20.6 percent in 2020, but most of that decline occurred between 2000 and 2010. Average rates were generally stable between 2010 and 2020.

The OECD data on 101 jurisdictions show that total revenues from corporate income taxes were nearly $1.5 trillion in 2016.

Tax Incentives vs. Minimum Taxes

Another important takeaway from the report is the contradictions between two recent policy trends. The first trend is the growth of tax subsidies for research and development (R&D) and income from intangible assets. Tax support for R&D expenses among the 36 OECD countries grew by 112 percent from 2006 to 2007. In 2019, 30 of the 36 countries provided tax relief for R&D spending. Tax benefits for income from intellectual property are also common these days, providing anywhere from a full exemption to a 40 percent discount off the standard corporate tax rate. The patent box policies commonly provide tax subsidies to income from patents, but in some cases copyrighted software and other intangible assets can also benefit.

While these incentives are often designed with the objective of spurring innovation and high-value investment, they can lead to distortions in the location of business activities. It is also a subject of debate as to whether and to what extent the policies actually spur new innovative activities or if they simply provide opportunities to relocate patents or research activities.

The second trend is the movement toward policies that would undercut the availability of those tax incentives. The new report provides an initial look (with serious caveats) at 2016 country-by-country data for multinational activities that is likely to be used to support policy arguments in favor of a global minimum tax.

If low levels of taxation and targeted tax subsidies are creating gravity wells for multinational profits that create distortions across the global economy, a minimum tax could neutralize those incentives. But it would also increase the cost of investment, leading to higher effective tax rates on cross-border investments and potentially slowing global economic integration and growth. The technical design challenges are legion.

These two policy trends—subsidies for R&D investment and income from patents alongside a push for a unified approach on a global minimum tax—reveal the challenges of corporate taxation in the 2020s.

Tax Conflicts for a New Decade

If the story of the last decade was a general stabilization of corporate tax revenues and statutory corporate rates alongside major changes to address profit-shifting opportunities, then the story of this decade could be one of tax conflicts.

Those conflicts could be between countries over the design of a minimum tax and what sort of policies that minimum tax would conflict with. Or, as we’ve seen in recent months, a rising conflict over taxing digital businesses that could lead to a harmful tax and trade war.

Conflict is part and parcel to the politics and compromise, even in tax policy. However, ongoing, continuous conflicts over tax at the international level can work against global integration and growth.

Countries will continue to respond to incentives to attract investment, in some cases by creating a neutral playing field and others by providing specific tax subsidies. Countries will also continue to propose new ways to tax businesses and seek changes that impact not only how much multinational businesses pay in tax, but also where they owe tax. However, without common principles or goals, global corporate tax conflicts will continue.

Source: Tax Policy – Decades in Corporate Taxation