Tax Policy – What Happens with State Excise Tax Revenues During a Pandemic?

Understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on state revenues is one of the key tasks ahead for state governments. The upending of American life necessitated by efforts to slow the spread of the virus will have profound effects on how Americans and American companies make and spend money—in turn, disrupting revenue collections for state governments. Morgan Stanley estimates that U.S. GDP might decline as much as 30 percent in the second quarter of 2020—figures not historically seen in peacetime. While analysts hope that the economy will bounce back in the third and fourth quarters of the year, much remains unclear. In any event, this crisis will be a test for state governments, which will see reduced revenues and skyrocketing expenses.

This blog post will look at what we might expect from excise tax revenues. It examines the data from previous crises while acknowledging the fact that this pandemic looks very different from anything we have seen. The focus is alcohol, tobacco, and gas excise taxes as these are levied in all 50 states (and the District of Columbia) and, according to 2018 data, represents about 61 percent of states’ excise tax collections.

Lessons from the Great Depression

It has been almost a century since the Great Depression, and today’s economy operates very different than the economy in the 1930s. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to be the most severe shock to the American economy since the Great Depression. From 1929 to 1933, unemployment rose from 4 percent to 25 percent and GDP fell 46 percent. The shutdown of businesses across the U.S. during this pandemic may result in similar unemployment figures as well as double-digit declines in GDP, but in a matter of months rather than years.

The tax system and size of government was vastly different in the late 1920s. State and local governments relied mostly on property and gas taxes. The Great Depression reduced property tax revenues by almost 20 percent. This led to the development of a number of consumption-based taxes that are still on the books today. For instance, 22 states adopted general sales taxes during the Great Depression.

By 1939, 48 states had imposed excise taxes on liquor and 21 states had imposed excise taxes on cigarettes. (Cigarette taxes were a rarity before the Great Depression.) These excise taxes proved quite successful, raising more revenue than individual income taxes by 1940. During the 1930s, cigarette consumption per capita doubled from 1,000 cigarettes to around 2,000 cigarettes per year, which helped grow the tax base. Such developments today are inconceivable as the public understands the health risks of smoking, and alcohol consumption is stable. There are other excise taxes such as marijuana taxes and gambling taxes (once social distancing ends) which may provide some relief for states, but they are unlikely to provide long-term solutions to budget problems.

Lessons from the Great Recession

States rely less on excise taxes today than they did in 2008, when roughly 15 percent of state collections came from excise taxes. Today that figure is 11 percent. The revenue collected through excise taxes has been very stable in nominal terms, at $118 billion in 2008 and $117 billion in 2018.

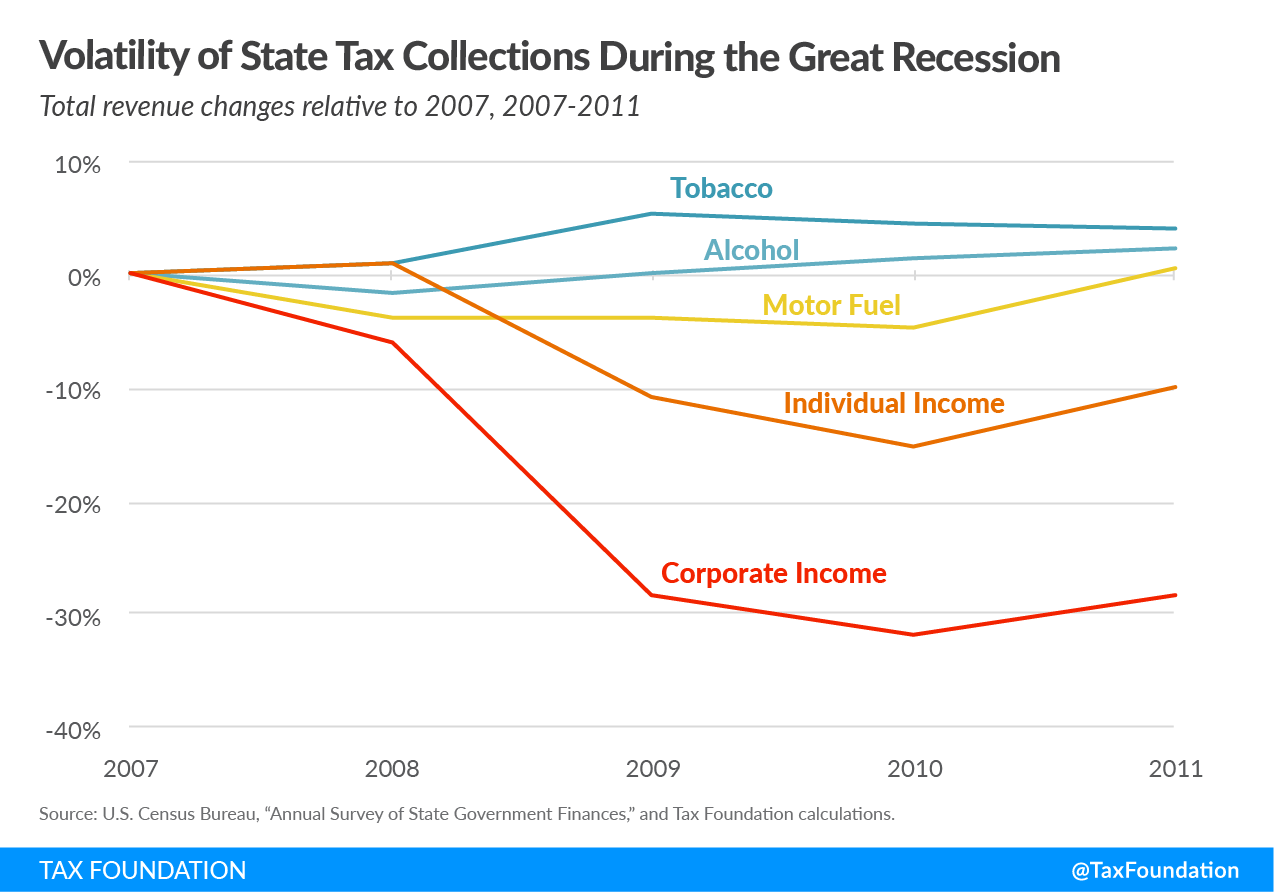

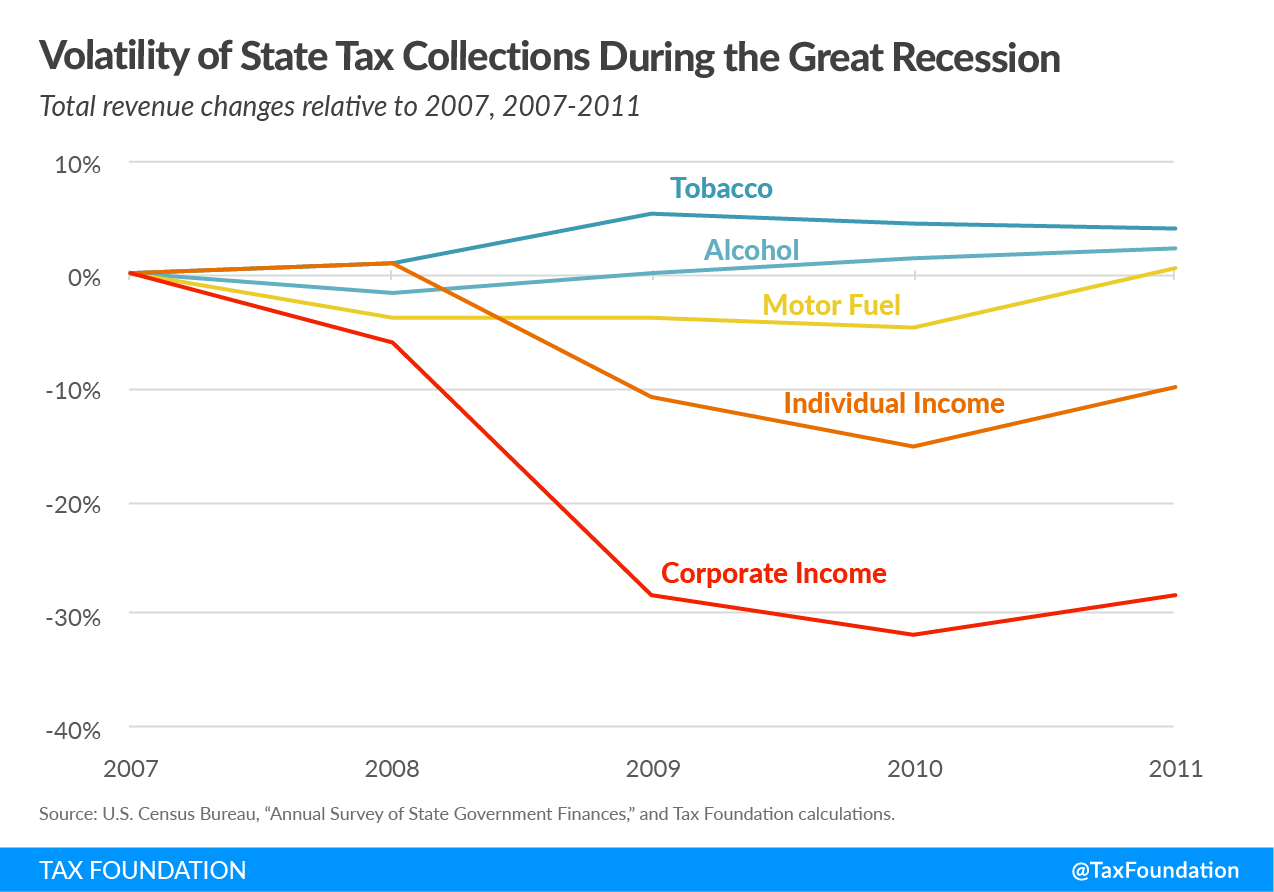

Looking at the figures below, it is clear that excise taxes were less affected than income taxes during the Great Recession. The same is true for general sales taxes. The relative stability of excise taxes compared to income taxes is not unique to the Great Recession. While most of us reduce some spending during an economic downturn, there is only so much we can—or are willing to—cut. For example, average spending on alcohol only declined 2.8 percent from 2007 to 2008. Spending on tobacco declined less than 2 percent. For comparison, real income declined 4.2 percent from 2007 to 2008, and the decline in taxable income was even more significant.

Alcohol tax collections remained almost constant during the Great Recession, motor fuel tax collections declined only 5 percent between 2007 and 2010, and tobacco tax collections actually increased (the result of higher rates), but individual income tax collections declined 15 percent and corporate income tax collections plummeted 32 percent.

The big difference between recessions of the past and the COVID-19 pandemic is social distancing, shelter-in-place-orders, and quarantines. These policies, intended to limit the spread of the virus, practically unplugs the economy. When most people avoid leaving their homes, consumption patterns must change accordingly. For instance, closing bars and restaurants will affect alcohol consumption even though analysts suggest that increased consumption at home may offset the decline somewhat (this will be limited if states shut down access to liquor as Pennsylvania did). It is unlikely that any increase in off-premise (brick and mortar) sales will offset the loss completely. In fact, on-premise consumption (at bars or restaurants) represents roughly a quarter of volume in the alcohol market. While off-premise sales are going up, there is almost no on-premise sales in many major cities. Further, if it turns out that the off-premise sales increase is merely consumers “stocking up,” the offsetting effect on excise revenues will be minimal.

Currently, people are being asked to stay at home and will thus purchase less motor fuel, which changes the picture. Major U.S. cities have seen traffic drop by as much as 40 percent. During the Great Recession people continued to travel unhindered, and the impact on gas tax revenues was limited.

Not only will this result in a reduction in gas tax collections, but toll collections are also likely to drop. With reductions in congestion, the incentive to pay a premium for express-lane access disappears. In addition, toll road pricing is sometimes based on the level of traffic. Interstate 66 in Northern Virginia is an example of one such road. A comparison of the historical estimate of a rush hour 8.5-mile commute from Northern Virginia to Washington, D.C. shows a dramatic change in cost. In fact, the cost dropped from an average of $25 (running four-week average) to $2 on March 24. These figures indicate that unlike in previous recessions, gas tax revenues are poised to decline.

Like gas tax and alcohol tax revenues, tobacco tax revenues were quite stable through the Great Recession. This was the result of a limited reduction in consumption combined with tax increases. In 2009, 15 states increased tobacco taxes, which increased the national mean cigarette excise tax from $1.18 per pack in 2008 to $1.34 per pack in 2009. However, it is unlikely that tobacco excise taxes will prove a significant source of revenue now. Tobacco excise taxes already have been increasing and in 2020 the average state cigarette excise tax is $1.81 per pack. In addition, about 20 percent of the population smoked in 2009, whereas only 14 percent smoke today.

Other Excise Taxes

Aside from the big three excise taxes discussed above, there are several other excise tax sources that are severely impacted by the pandemic.

Airline ticket excise taxes and passenger facility charges will drop dramatically as airline bookings decrease. United Airlines announced reductions in capacity by 50 percent for April and May.

Revenue from newer excise taxes like marijuana taxes will be determined by whether state governments include marijuana businesses as non-essential and prevent them from operating during state lockdowns. Excise taxes from both sports betting and gambling at casinos will almost disappear given that most casinos are closed and almost all sports suspended.

Excise taxes on amusement—such as movie theaters, amusement parks, concert tickets, and sporting events—are also disappearing as gatherings above 10 people are inadvisable according to federal guidelines, not to mention states where people have been ordered to shelter in place. On a positive note, states that have broadened their sales tax base to include streaming services will capture some additional spending from quarantined Americans looking for anything to do.

Final Thoughts

States will have to consider the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on tax revenues. We can expect a combination of increases in state expenses and dramatic decreases in revenue in the short term. The challenge will be to develop strategies that are consistent with long-term sound tax policy and abstain from inventing harmful policies that might hurt economic growth on the other side of the crisis.

Source: Tax Policy – What Happens with State Excise Tax Revenues During a Pandemic?