Tax Policy – Can States Close Budget Deficits with Excise Tax Hikes?

Key Findings:

- The coronavirus pandemic affects almost every source of state revenue, and with the duration unknown, predicting economic outcomes will be difficult. Social distancing, stay-at-home-orders, and quarantines make the resulting recession fundamentally unique.

- Hospitality, leisure, and travel could be among the hardest hit industries. As a result, excise taxes and fees on air travel and hotel rooms (occupancy taxes) will plummet, jeopardizing funding for air traffic infrastructure projects in the states as well as local spending funded by occupancy taxes.

- With people staying at home, fewer cars are on the roads. As of early April, personal travel had declined 47 percent, which will lead to a significant reduction in gas tax revenue in the states.

- Tobacco tax revenue may be relatively stable as consumption is not necessarily affected by social distancing. But consumption overall is decreasing, as is the tax revenue. The relatively new vaping taxes have generally raised little revenues.

- Closures of bars and restaurants may affect alcohol tax revenue even though off-premise sales (at liquor stores and grocery stores) had increased in the early weeks of the pandemic. However, squeezing more revenue out of alcohol excise taxes through increasing rates could impair bars’ and restaurants’ ability to survive by hurting their margins when they reopen.

- Recreational marijuana and sports betting represent new revenue opportunities for states. Many have already either legalized and taxed one of these products or considered doing so; more may follow. But doing so is highly unlikely to raise much revenue in the short term.

Introduction

The pandemic-induced economic crisis will affect almost every meaningful source of state revenue. Historically, income taxes are more volatile than sales and excise taxes and fall more sharply during a recession, but this crisis is unique inasmuch as social distancing and shelter-in-place orders, along with mandatory closures of many nonessential businesses, have led to a sharp contraction of consumer spending. Moreover, the goods and services seeing spikes in demand, like groceries and digital entertainment, are less likely to be subject to state sales tax.[1]

The contraction in spending is affecting excise tax revenues and, in some cases, revenue may be eliminated entirely. Telework and other reductions in travel mean motor fuel taxes will plummet, as will special excise taxes on tourism and hospitality. Closures of casinos, bars, and other establishments responsible for considerable “sin tax” revenue will also impact states’ bottom lines.[2]

This paper examines what to expect in terms of excise tax revenue and discusses why increased excise tax rates do not offer a sustainable solution to budget deficits. The paper is split in three parts: travel-related excise taxes, sin taxes, and new excise revenue sources.

Revenue Decline

Faced with extraordinary uncertainty about the depth and duration of this crisis, states must find a way to balance budgets in the years to come. That will require dramatic steps as economic growth will turn sharply negative in the short run. The longer lockdowns continue, the more severe the economic downturn, not just due to a longer initial period of economic contraction, but also due to a reduction of business capital and a breakdown in supply chains, which will make it more difficult for businesses to return operations to pre-coronavirus levels. The devastating effects of the crisis are already evident by staggering unemployment figures.[3]

A pandemic of this magnitude is an unprecedented event in modern times, and predicting economic outcomes is difficult. The travel, leisure, and hospitality industries may expect consequences similar to those following the September 11th attacks, though for a more extensive duration. Certain reactions in consumer behavior could prolong the crisis for these industries.

One way of putting some context to the crisis ahead is to look at the aid package requested by the National Governors Association. On April 11, Governor Larry Hogan (R-MD) and Governor Andrew Cuomo (D-NY) requested $500 billion in federal aid to cover revenue shortfalls. That number represents 56 percent of states’ general fund tax revenue for fiscal year 2020.[4]

Looking specifically at state excise tax revenue, in the first two quarters of 2019 states collected $26 billion in gas taxes, $3.5 billion in alcohol taxes, $4 billion in amusement taxes, and $9 billion in tobacco taxes ($42.5 billion total). Depending on the duration of the lockdowns, the impact on each of these major excise revenue categories could be larger or smaller. However, a conservative expectation of a 10 percent reduction in each would leave states with a revenue shortfall of roughly $4.25 billion.[5]

Inevitably, states will look for new revenue as traditional sources dry up. However, lawmakers should remain cautious when designing new excise taxes or increasing rates on existing levies. Excise taxes can be part of a revenue picture as we come out on the other side of business closures and stay-at-home orders, but excise revenue is unlikely to be a successful long-term strategy for closing budget holes.

Hardest Hit Excise Categories

Travel-related excise tax sources will be more affected than others due to the nature of the crisis and the mitigation policies designed to curb the spread of the coronavirus.

There is no doubt that government’s user-fee based transportation revenue will decline, but how much exactly is hard to estimate. The American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials (AASHTO), which represents departments of transportation in all 50 states, has asked Congress for a $50 billion grant to cover expected revenue deficits through 2021. AASHTO estimates that revenue (projected based on $111 billion in revenue in FY2019) from transportation-related sources such as highway tolls, airplane tickets, motor fuel taxes, and state vehicle taxes will drop 30 percent.[6]

Air Traffic

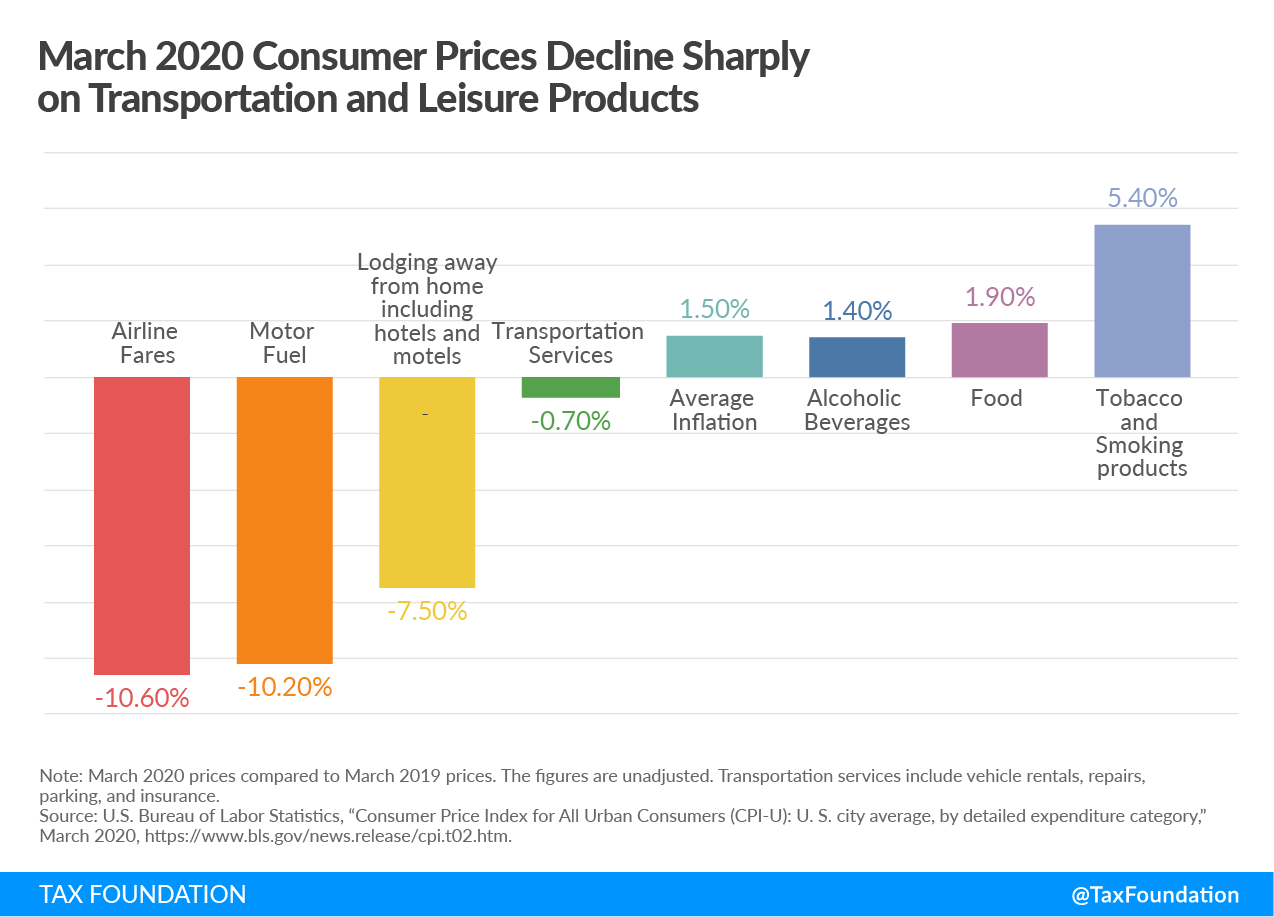

The future is uncertain for both international and domestic travel, but it is highly likely that the crisis will impact commercial airlines for a long time. As of early April, domestic air travel had declined about 40 percent, and many planes had been grounded.[7] This had resulted in airfare prices declining 10.6 percent compared to the same period last year.[8] In the longer term, travel will be impaired, not only by policy, but by consumer choice if people react to coronavirus as they historically have done to terror attacks. For instance, tourism in New York did not return to pre-September 11th levels for five years.[9]

The federal government collected close to $16 billion in fiscal year 2019 from excise taxes on airline tickets. The revenue funds airports, facilities, research, and operations under the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).[10]

The federal government charges an excise tax on all domestic travel of 7.5 percent. In addition, there is a Flight Segment Tax of $4.20 per segment. Finally, passengers pay a September 11th tax of $5.60 to the federal government per one-way trip.[11]

Local airports can charge a fee (and almost all do) called the Passenger Facility Charge (PFC), which is meant to cover the costs of maintaining and improving airports. The PFC is capped at $4.50.

Increasing the excise taxes or fees related to air travel right now is unlikely to increase revenue in any meaningful way—in fact, it may do more harm than good. Air traffic could be years away from more normal operations and increasing tax burdens could halt the industry’s ability to rebound from the crisis.

Short-Term Lodgings

Across the country, many states and localities levy an excise tax on short-term lodging. The revenue from these taxes is often earmarked for tourism promotion or as additional general funds for localities. Given that few people are going to conferences, on vacations, or on weekend-getaways, both states and localities must expect that this revenue stream will largely disappear in the short run.[12] The lack of demand has led to a 6.8 percent decline in the price of short-term lodgings compared to the same period last year.[13]

Once the economy revs up, it could be tempting for some policymakers to attempt to export more of the tax burden to visitors, but this should be avoided. While tax exporting may succeed in disproportionately burdening nonresidents, the taxes have negative economic effects for the taxing jurisdiction. In addition to lowering the quantity of lodging demanded, there is evidence that consumers will travel to lower-tax jurisdictions nearby.

Motor Fuel

According to INRIX, a traffic data analytics company, compared to the week of February 22-February 28, just before the pandemic was officially called, personal travel nationwide for the week of March 30-April 3 decreased by 47 percent. Trucking is also down, but not to the same degree, as businesses (especially retail stores and pharmacies) still need inventory. Long haul trucking is down 6 percent while local commercial travel is down 26 percent. Such a decline will lead to a dramatic drop in gas tax revenue.[14]

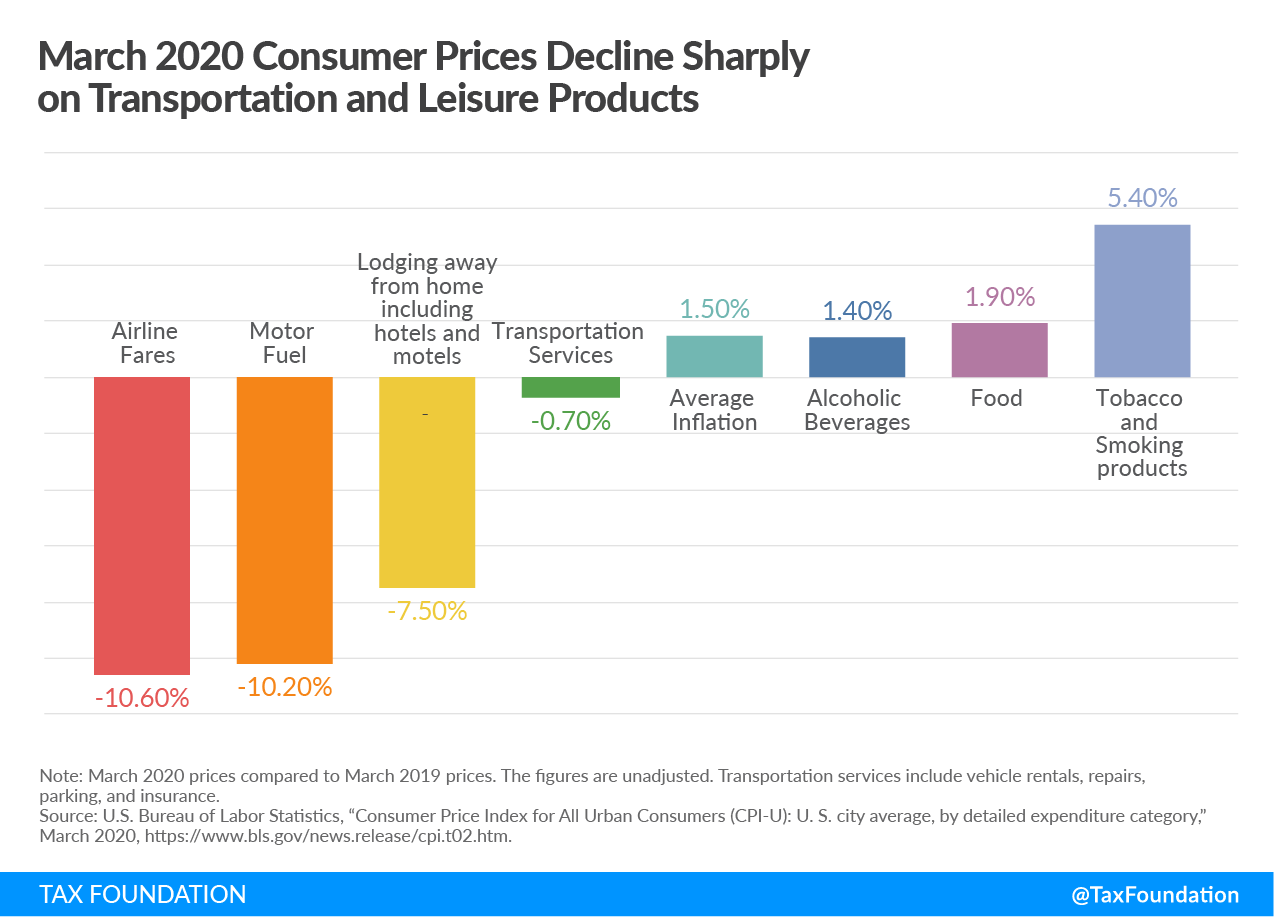

In 2018 (the latest data), state governments raised $48.2 billion in motor fuel excise tax revenue.[15] Revenue from these taxes is largely used to fund infrastructure maintenance and new projects. Declines in receipts will not affect all states similarly, as the amount of state and local road spending covered by gas taxes, tolls, user fees, and user taxes varies widely: from 6.9 percent in Alaska to 71 percent in Hawaii. In the contiguous 48 states, North Carolina relies the most on dedicated transportation revenues (63.6 percent), while North Dakota relies the least (17.5 percent). States like Alaska and North Dakota keep their transportation taxes low in the same way that they keep all taxes on state residents low—by exporting taxes, primarily through the severance tax. Incidentally, these states should also see declines related to gasoline as the low price of crude oil will burn a hole in their budgets.[16]

Toll collections are also likely to drop. With reductions in congestion, not only will traffic on all roads, including toll roads, decline, but the incentive to pay a premium for express-lane access will disappear. In addition, toll road pricing is sometimes based on the level of traffic (congestion pricing). While some states may look to increase tax rates on gas, 31 states have already increased gas taxes in the past decade.

Sin Taxes

The sin tax category includes taxes on products which are considered to be harmful to consumers, and include taxes on alcohol, tobacco, and vaping. Taxes on sugary beverages are also sin taxes, though they are not included here due to their relative rarity.

Increasing these sin taxes may be alluring to some lawmakers as tobacco and alcohol are considered relatively inelastic. That means consumption does not decrease as much as the price increases. Further, it can be politically easier to increase these narrow taxes on “sinful” products rather than increasing taxes on a larger part of the constituency.

Tobacco

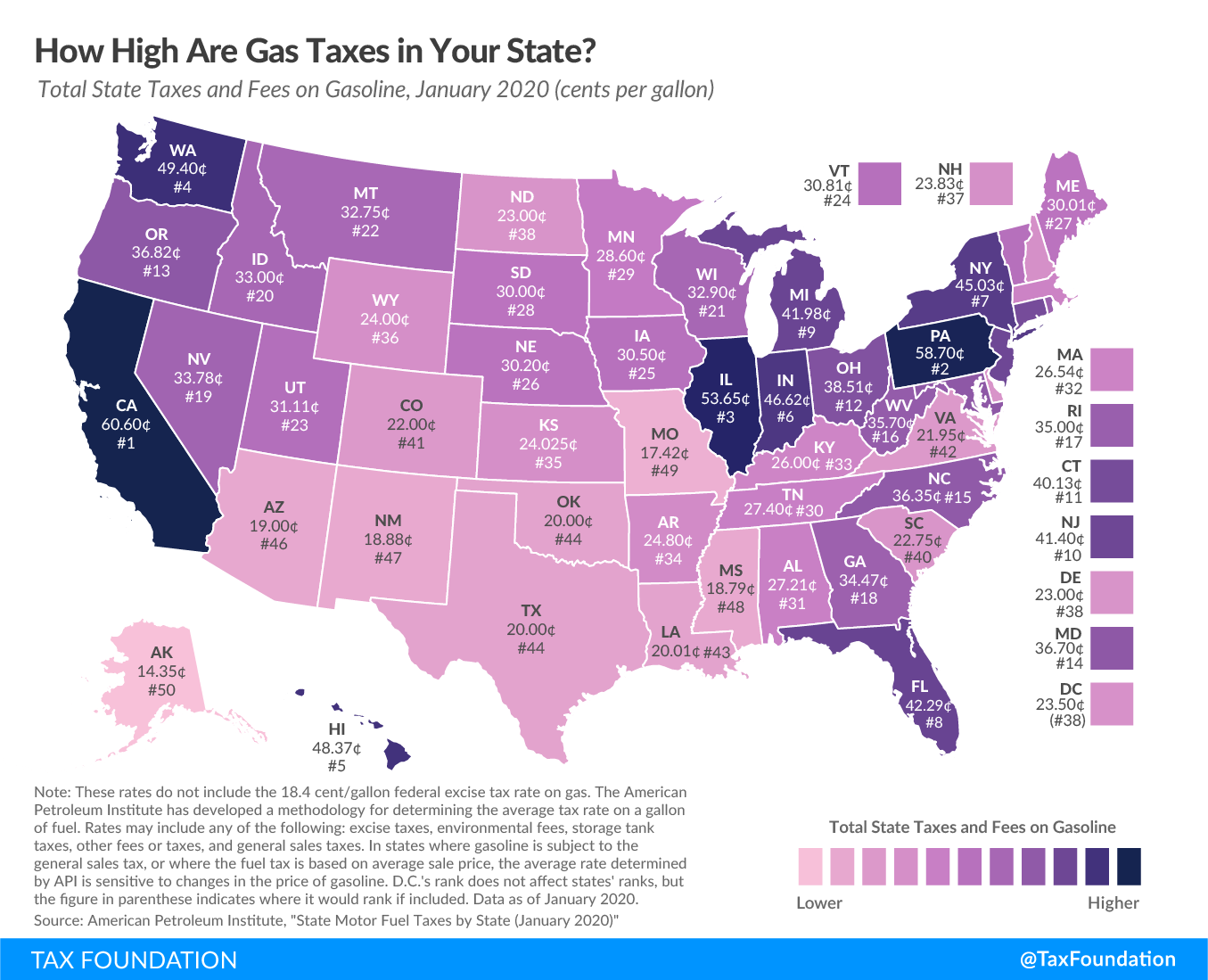

Tobacco taxes have a history closely connected to recessions. In fact, cigarette taxes were a rarity before the Great Depression, but by 1939, 21 states had imposed excise taxes on cigarettes. In the 1930s, tobacco taxes were a growing revenue source for governments as cigarette consumption per capita doubled from 1,000 cigarettes to around 2,000 cigarettes per year during that decade.[17]

Through the Great Recession, tobacco tax revenues were quite stable as a result of a limited reduction in consumption combined with tax increases. In 2009, 15 states raised tobacco taxes, which increased the national mean cigarette excise tax from $1.18 per pack in 2008 to $1.34 per pack in 2009.[18] However, it is unlikely that tobacco excise taxes will prove a significant source of additional revenue now. Tobacco excise taxes have been increasing in the last decade, and in 2020 the average state cigarette excise tax is $1.81 per pack. In addition, about 20 percent of the population smoked in 2009, whereas only 14 percent smoke today.[19]

While it may be an option for some states to increase tobacco excise taxes for a short-term bump in revenue, it is not a solution for long-term budget issues. Besides being a highly regressive tax increase, a guiding principle is that excise taxes should only be levied when appropriate to capture some externality or to create a “user pays” system—not as a general revenue measure. Due to their narrow base, they are not a sustainable source of revenue for general spending priorities.

Vapor Taxes

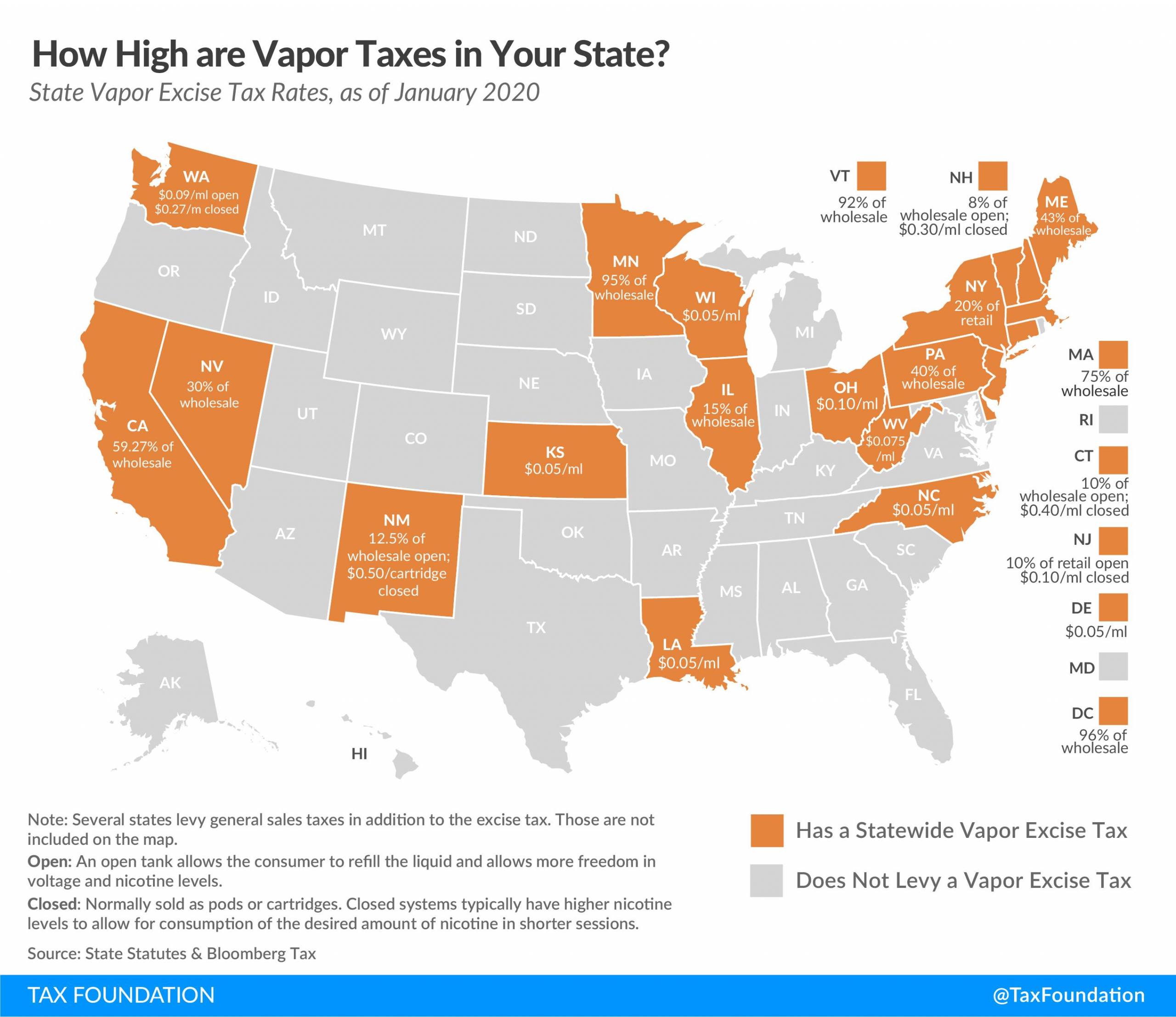

Currently, 23 states and the District of Columbia have enacted a tax on vapor products. Eleven of these states introduced their tax in 2019 and more states will likely pass tax bills on vapor products in 2020.

The coronavirus pandemic may encourage some states to look to vaping products as a potential revenue source, but lessons from states with established taxes should be noted. Revenues have generally been low and solving that with high state tax rates could fuel a black market (disparities in tax rates among states incentivize smuggling) and hurt public health by limiting smokers’ ability to switch from more harmful combustible tobacco products.[20] By looking at cessation behaviors in lieu of a tax increase on vapor products, a recent publication found that 32,400 smokers in Minnesota were deterred from quitting cigarettes after the state implemented a 95 percent excise tax on vapor products.[21]

Revenue collected through excise taxes on nicotine products should not be considered stable—excise revenues seldom are—and the market is both young and volatile. It would be problematic to base long-term budgeting decisions on this revenue stream due to a shortage of reliable consumer data. Further, there may be federal action related to flavors or taxation that could dramatically change any revenue forecast.

Alcohol

The alcohol excise tax is one of the oldest taxes in America. Its history goes back to the early days of the republic, when a tax was imposed on whiskey during George Washington’s administration to pay back war debts. It would routinely be levied to pay down similar war debts until Prohibition. After the Great Depression, President Franklin Roosevelt supported ending Prohibition partially to open a new revenue source for governments.[22]

Today, an alcohol excise tax is imposed in all 50 states, in the District of Columbia, and by the federal government. According to some reports, excise tax revenue of alcohol may not suffer as much as other categories. According to consumer sales data, sales of alcohol overall were up 55 percent in the week ending March 21. That includes liquor sales increasing by 75 percent, wine by 66 percent, and beer sales by 42 percent. Much of the sale has moved online resulting in online alcohol sales increasing by 243 percent.[23]

However, it is unlikely that any increase in off-premise (brick and mortar) sales will offset the loss from closed bars and restaurants (on-premise) completely. In fact, consumption on-premise represents roughly a quarter of volume in the alcohol market—and there is almost no on-premise sales in many major cities.[24] Further, if it turns out that the off-premise sales increase is merely consumers “stocking up,” the offsetting effect on excise revenues will be minimal. There are some indications that the increase in sales was short-lived as the increase slowed in the week ending March 28.[25]

While governments tax alcohol based on volume and thus are unaffected by whether alcohol is sold in a store or at a bar, the industry margins are significantly higher at restaurants and bars. In fact, despite on-premise representing only a quarter of the volume, it represents half of the value.

It is still unclear what the market for alcohol will look like in the coming months, but increasing excise taxes on alcohol could be damaging for companies that are already threatened on their margins. Further, when restaurants and bars can reopen, additional tax burden could limit their ability to rebound. Increasing the alcohol tax rate would, like increasing the tobacco tax rate, be highly regressive, disproportionately burdening low-income Americans.[26]

New Revenue

Emerging trends in state taxation include marijuana and sports betting. They are highlighted here for their modernity even though they could be considered sin taxes as well. While these both offer an opportunity for new revenue, they are complicated long-term projects that cannot easily be reversed or undone.

Recreational Marijuana

Diminishing receipts from traditional sources of revenue combined with stories of growing marijuana sales might make some states consider a legalization of and excise tax on marijuana.[27] Though very unlikely to deliver short-term revenue, legalization can be part of a revised revenue picture in the years ahead. However, given the novel nature of the markets, states should expect some volatility in revenue and should not appropriate revenue to arbitrary spending priorities.

In the states that have legalized so far, it has generally taken some time for markets to become capable of delivering sizable returns. There are significant costs associated with building the system required to operate a recreational marijuana industry.[28]

These lessons have prompted states to be cautious in revenue projections and appropriations rather than to present legalization as a long-term budget fix. As an example, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo (D), who has tried and failed to legalize marijuana for the past two years, [29] had proposed a budget with a projected revenue of a mere $20 million in a first year of legalization. In Maryland, a commission that was working on potential legalization pushed back any further action due to the complexity of the regulation.[30] To add to the complexity, any federal action on marijuana could skew the projections in any direction.

It is important to get the regulatory and tax structure right as brick-and-mortar dispensaries will be competing with black and gray markets, and setting tax rates too high could keep consumers in untaxed markets.

| State | Tax Rate |

|---|---|

| Alaska | $50/oz. mature flowers; $25/oz. immature flowers; $15/oz. trim; $1 per clone; |

| California | 15% retail excise tax; $9.65/oz. flowers & $2.87/oz. leaves cultivation tax; $1.35/oz fresh cannabis plant |

| Colorado | 15% excise tax (levied on wholesale at average market rate); 15% excise tax (retail price) |

| Illinois | 7% excise tax of value at wholesale level; 10% tax on cannabis flower or products with less than 35% THC; 20% tax on products infused with cannabis, such as edible products; 25% tax on any product with a THC concentration higher than 35% |

| Maine (a) | 10% excise tax (retail price); $335/lb. flower; $94/lb. trim; $1.50 per immature plant or seedling; $0.30 per seed |

| Massachusetts | 10.75% excise tax (retail price) |

| Michigan | 10% excise tax (retail price) |

| Nevada | 15% excise tax (fair market value at wholesale); 10% excise tax (retail price) |

| Oregon | 17% excise tax (retail price) |

| Washington | 37% excise tax (retail price) |

|

(a) Maine legalized recreational marijuana in November 2016 by ballot initiative. The state is slated to implement a legal market later in 2020. Note: District of Columbia voters approved legalization and purchase of marijuana in 2014 but federal law prohibits any action to implement it. In 2018, the New Hampshire legislature voted to legalize the possession and growing of marijuana, but sales are not permitted. Alabama, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Tennessee, and Wisconsin impose a controlled substance tax on the purchase of illegal products. Several states impose local taxes as well as general sales taxes on marijuana products. Those are not included here. Sources: State statutes; Bloomberg Tax. |

|

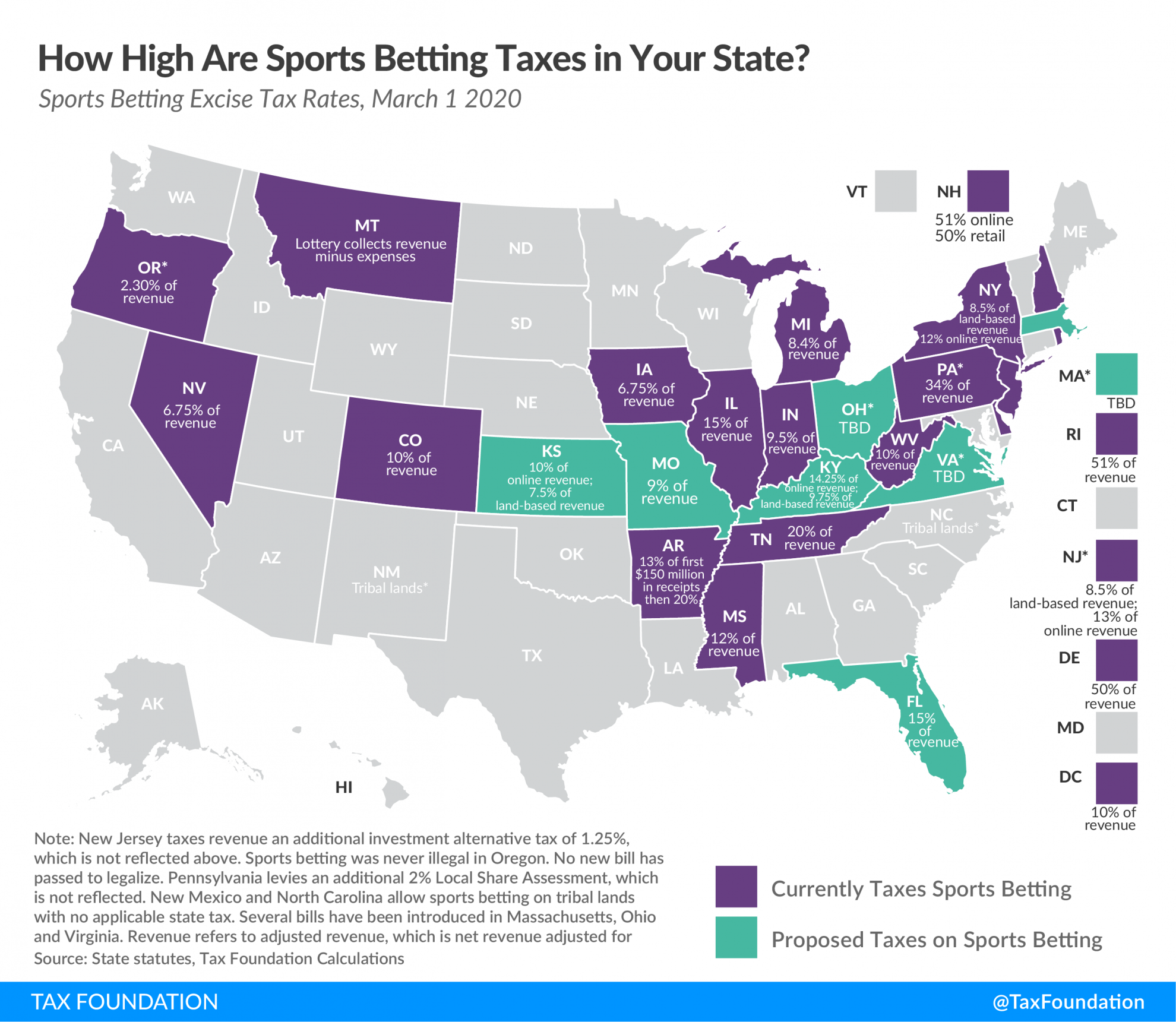

Wagering

In 2019, eight states approved sports betting and taxation regimes, joining the existing 12 states and the District of Columbia which already had active sports betting markets. Of those 21 jurisdictions, 14 currently have active markets. Ten of those markets allow mobile betting while four only allow physical sportsbooks.[31]

Like marijuana, new revenue is unlikely to materialize in the short run. In states that do not already allow betting, setting up sports betting operations requires the development of a new regulatory framework. In addition, most sport leagues and events have been postponed to curb the spread of the coronavirus. For these reasons, both introduction of sports betting and adjustment of tax rates are unlikely to yield meaningful revenue returns in the short term.

When sports return—perhaps without crowds—it is a real possibility that online sports betting could rebound rather quickly. If moderate social distancing will be mandated for a prolonged period, brick and mortar casinos and physical sportsbooks will not be able to compete with online sports betting.[32]

In the long run, sports betting represents a real opportunity for new revenue for states—especially if they develop an appropriate regulatory and tax framework, which allows the industry to grow.

Concluding Thoughts

As policymakers get a better understanding about the size of the budget difficulties, they will have to make some tough decisions. Given the severity and potential length of the present crisis, states must carefully examine their current expenditures.

States adopting budgets now may wish to prioritize expenditures, granting governors the authority (where they currently lack it, and where it is consistent with state constitutions) to reduce some spending throughout the year to adjust to uncertain revenues. If budgeting for the higher bound of revenue estimates, they may wish to adopt budgets which maintain cash reserves, as it is easier to bring spending back online if revenues recover or additional federal aid becomes available than it is to make cuts toward the end of the year.

This paper examines whether excise taxes are a solution to budget deficits, and while the short answer to that question is no, there are of course nuances. Excise taxes can play a role in state revenues even as policymakers appreciate that excise taxes are not viable long-term revenue tools for general spending priorities.

Excise revenue from the travel industry could suffer for an extended period of time depending on consumer reaction to the pandemic, and increasing excise tax rates on airline tickets or hotels is unlikely to yield any positive result. Significant growth in revenue from both tobacco and alcohol as a result of growth in consumption is both unlikely and unwanted. Revenues from marijuana and sports betting are long-term projects, which states should not pursue for a short-term revenue bump. Federal uncertainty surrounding both vaping and marijuana make it even more difficult for states to project long-term revenue from these sources.

For these reasons, revenue collected through excise taxes should inasmuch as possible be allocated to spending related to the taxed activity or good. They are too volatile and unreliable to rely on for long-term budget priorities.

[1] Jared Walczak, “State Strategies for Closing FY 2020 with a Balanced Budget,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 2, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/fy-2020-state-budgets-fy-2021-state-budgets/.

[2] Ulrik Boesen, “What Happens with State Excise Tax Revenue During a Pandemic?” Tax Foundation, Mar. 25, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/happens-state-excise-tax-revenues-pandemic/.

[3] Jared Walczak and Tom VanAntwerp, “A Visual Guide to Unemployment Benefit Claims,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 9, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/unemployment-insurance-claims/.

[4] The Office of Governor Larry Hogan, “Nation’s Governors Urge Federal Leaders to Provide Immediate Fiscal Relief for States,” Apr. 11, 2020, https://governor.maryland.gov/2020/04/11/nations-governors-urge-federal-leaders-to-provide-immediate-fiscal-relief-for-states/.

[5] United States Census Bureau, “2019 Quarterly Summary of State & Local Tax Revenue Tables,” 2019, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2019/econ/qtax/historical.Q2.html.

[6] American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, “AASHTO Asks Congress For $50B Fiscal Backstop For State DOTs,” Apr. 10, 2020, https://aashtojournal.org/2020/04/10/aashto-asks-congress-for-50b-fiscal-backstop-for-state-dots/.

[7] Bill Chapell, “Coronavirus: U.S. Still Seeing Thousands Of Flights, Despite A Drop In Air Travel,” NPR, Mar. 30, 2020, https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/03/30/824043342/coronavirus-u-s-still-seeing-thousands-of-flights-despite-a-drop-in-air-travel.

[8] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Consumer Price Index Summary,” Apr. 10, 2020, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/cpi.nr0.htm.

[9]Jonathan Wolfe and Nick Corasaniti, “New York Today: Terrorism and Tourism,” The New York Times, Nov. 3, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/03/nyregion/new-york-today-terrorism-and-tourism.html.

[10] Federal Aviation Administration, “Airport and Airway Administration Trust Fund (AATF) Fact Sheet,” April 2020, 5, https://www.faa.gov/about/budget/aatf/media/aatf_fact_sheet.pdf.

[11] Ulrik Boesen, “Understanding the Price of Your Plane Ticket,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 28. 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/understanding-the-price-of-your-plane-ticket/.

[12] Andres Viglucci, “South Florida tourism bureaus imperiled as coronavirus slashes hotel tax collections,” Miami Herald, Apr. 8, 2020, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/business/tourism-cruises/article241813616.html.

[13] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Consumer Price Index Summary.”

[14] Mark Burfeind, “INRIX U.S. National Traffic Volume Synopsis: Issue #3 (March 28-April 3, 2020),” INRIX, Apr. 6, 2020, https://inrix.com/blog/2020/04/covid19-us-traffic-volume-synopsis-3/.

[15] United States Census Bureau, “2018 State Government Tax Tables,” 2018, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2018/econ/stc/2018-annual.html.

[16] Janelle Cammenga, “How Are Your State’s Roads Funded?” Tax Foundation, Sept. 11, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/states-road-funding-2019/.

[17] Institute of Medicine, ”Ending the Tobacco Problem: A Blueprint for the Nation,” The National Academies Press, 2007, 41, https://doi.org/10.17226/11795.

[18] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “State Cigarette Excise Taxes — United States, 2009,” Apr. 9, 2010, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5913a1.htm.

[19] Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, “State Cigarette Excise Tax Rates & Rankings,” Jan. 14, 2020, https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/factsheets/0097.pdf.

[20] Ulrik Boesen, “Taxing Nicotine Products: A Primer,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 22, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/taxing-nicotine-products/.

[21] Henry Saffer, Daniel L. Dench, Michael Grossman, and Dhaval M. Dave, “E-Cigarettes and Adult Smoking: Evidence from Minnesota,” National Bureau of Economic Research, December 2019, https://www.nber.org/papers/w26589.

[22] Lyman Stone and Richard Borean, “When Did Your State Adopt Its Tax on Distilled Spirits?” Tax Foundation, Aug. 5, 2014, https://taxfoundation.org/when-did-your-state-adopt-its-tax-distilled-spirits/.

[23] Sara Fischer, “Virus vices take a toll on Americans,” Axios, Apr. 5, 2020, https://www.axios.com/coronavirus-vices-alcohol-marijuana-food-23f02d5e-b82b-4944-8609-b4479af1070e.html.

[24] Statista, “Alcoholic Drinks,” accessed Apr. 9, 2020, https://www.statista.com/outlook/10000000/109/alcoholic-drinks/united-states.

[25] Justin Kendall, “Nielsen: Alcohol Sales Slow in Off-Premise Retailers for Week Ending March 28,” Brewbound, Apr. 6, 2020, https://www.brewbound.com/news/nielsen-alcohol-sales-slow-in-off-premise-retailers-for-week-ending-march-28.

[26] Scott Greenberg, “Distributional Effects Should Be Measured in Percentages, not Dollars,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 5, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/distributional-effects-should-be-measured-percentages-not-dollars/.

[27] Sara Fischer, “Virus vices take a toll on Americans.”

[28] Ulrik Boesen, “States Move on Recreational Marijuana,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 17, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/pennsylvania-marijuana-new-mexico-marijuana/.

[29] Ulrik Boesen, “New York’s Road to Legalized Marijuana,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 23. 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/new-york-legalize-marijuana/.

[30] Mike Detmer, “Policy group previews legislative session,” The Dorchester (Easton, Md.) Star, Nov. 29, 2019,

[31] Ulrik Boesen, “Sports Betting Might Come to a State Near You,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 3, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/legal-sports-betting-states/.

[32] Casino taxes represent a significant source of revenue for some states—especially Nevada. This revenue stream is currently not available as casinos are closed. The activity cannot be moved online as it is illegal to operate online casinos in the U.S.

Source: Tax Policy – Can States Close Budget Deficits with Excise Tax Hikes?